Economic Perspectives January 2021

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- After a year of unprecedented disruptions, the global economy is poised to rebound in 2021. We maintain our economic outlook for a gradual recovery, that should build significant momentum after some initially challenging winter months in the grip of the virus. A somewhat slow start of vaccination campaigns across the advanced economies is set to accelerate substantially in the coming months, allowing for a relatively swift recovery in economic activity later in the year. Backed by ongoing heavy policy support, a post-pandemic synchronised recovery is expected to carry well into 2022 in both advanced economies and emerging markets.

- Activity in the euro area remains heavily affected by virus dynamics. There are, however, encouraging signs of resilience, particularly a rebound in sentiment indicators. Furthermore, industrial production remains on a strong footing, partly offsetting lockdown-induced weakness in services. Against this background, we expect Q4 2020 growth to have contracted, but somewhat less than previously envisaged. The recently extended lockdowns reinforce our view for sluggish activity in Q1 2021 before the boost from vaccination to growth starts materialising. Overall, we have revised the euro area outlook for 2020 and 2021 slightly upward to -7.2% and 3.1%, respectively. In 2022, we pencil in a major payback from the pandemic with annual growth of 4.2%.

- A last-minute trade deal between the EU and UK was finally agreed in late December. The most important point is that a deal was reached, avoiding a ‘cliff edge’ outcome and the additional economic dislocation from the sudden imposition of tariffs and other major impediments at a point when European economies are already facing severe challenges. However, the limited nature of the deal reached means that the Brexit story is far from finished and remaining risks highlight the fragile nature of international economic relations at present.

- The US economy also shows signs of resilience amid a surging number of new Covid-19 cases. High frequency indicators, however, paint a mixed picture, with particularly disappointing December labour market data. On the bright side, the approved USD 900 billion fiscal package, and the prospect of a further round of stimulus as a consequence of the political ‘blue wave’ with Democrats now having effective control of both chambers of Congress should provide a boost to the US economy. Our annual growth outlook has been marginally upgraded to -3.5% in 2020, and 4.2% in 2021. We expect a slowdown in real GDP growth to 2.5% in 2022.

- The recovery in China continues amid some normalisation in the pace of economic growth following the strong rebound in the second half of 2020. Industrial production growth stabilised, while retail trade keeps catching up. External trade data, particularly on the export side, also suggest that the recovery is on track. As a result, we forecast annual real GDP growth of 2.1% in 2020, followed by strong (albeit somewhat mechanically elevated) growth of 8.5% in 2021 and 5.2% in 2022.

- On the monetary policy front, we expect major central banks to maintain a highly accommodative stance. The ECB has extended its policy support in December, including both the pandemic asset purchases and long-term refinancing operations. While inflation is set to gradually pick up from negative territory, it will remain below the inflation target, prompting the ECB to keep its policy rates unchanged at least until end-2022. In the US, the Fed is also expected to keep the rates at the current low level, while maintaining sizable asset purchases. This is underpinned by changed forward guidance that draws on the Fed’s policy review of last year, which indicated that achieving ‘maximum employment’ has taken precedence over the price stability goal.

The global economy has turned the page on the year like no other. As a response to the once-in-decades Covid-19 pandemic, governments were forced to impose strict lockdowns, resulting in the unparalleled economic downturn across the globe. While massive policy support cushioned the economic shock, the virus has affected almost every aspect of our lives, causing many households and businesses to struggle. After a year in the grip of the virus, there is, however, reason to be more optimistic about the economic outlook for 2021. As already flagged in our December edition, we maintain the view that the world economy has entered the ‘end phase’ of the pandemic. Most recently, this has been bolstered by the successful rollout of the vaccination campaigns in many countries, setting a stage for a strong post-pandemic recovery.

Challenging winter before a vaccine-led rebound

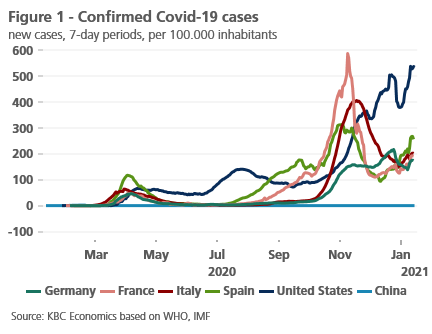

A post-pandemic recovery will nonetheless take some time to materialise. More specifically, we expect it will follow a period of subdued economic activity in winter months, particularly in the euro area. A weak near-term economic outlook reflects the worrying dynamics of the virus and renewed lockdowns. Both the US and Europe continue to struggle with elevated numbers of new Covid-19 cases, though there are notable disparities in infection rates across European countries (figure 1).

What is particularly concerning is the new more infectious strain of the virus that has been spreading rapidly in the UK (and beyond), forcing local authorities as well as governments elsewhere in Europe to extend and even tighten lockdown measures. The adverse health situation reinforces our view that tight restrictions will have to be maintained in the coming months to alleviate the burden on healthcare capacity. On a more positive note, we saw encouraging signals of resilience in the last quarter of 2020, indicating that renewed lockdown measures are likely to result in a more limited economic impact than previously envisaged.

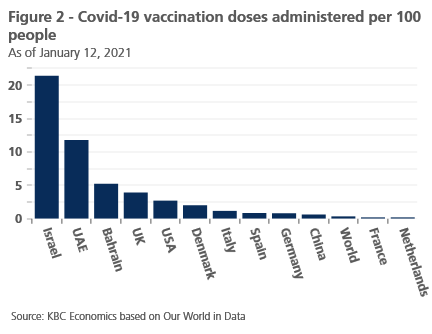

Looking beyond challenging winter months, we see a more favourable macroeconomic backdrop, backed by the gradual rollout of vaccines. In December, most western economies initiated vaccination campaigns, targeting high-risk groups, such as medical staff and elderly people. At the time of the writing, two vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna have been approved for emergency authorisation in the US and the European Union. Furthermore, other vaccine candidates are expected to be approved later in the year (according to the WHO, there are currently more than 230 vaccine candidates in total).

On the flip side, the vaccination campaigns have generally seen a slow start, highlighting the logistical challenges of the large-scale distribution. Among the advanced economies, Israel stands out with already 21.42 doses per 100 people administered (as of January 12, 2021), while others experience a significantly slower-paced distribution (figure 2). In the wake of a new strain of the virus, there appears even more urgency to speed up the rollout of vaccination. From the macroeconomic viewpoint, the pace of vaccination is important too, since the earlier distribution of vaccines is likely – all else equal – to limit the structural damage to the economy.

Despite some early hiccups, we project that effective vaccination campaigns are set to accelerate substantially in the coming months, allowing for a gradual normalisation in economic activity across advanced economies. Coupled with sustained and substantial policy stimulus, both on the fiscal and monetary fronts, our economic outlook, therefore, assumes the recovery gains pace in the latter part of 2021. In the euro area, the annual growth profile suggests a major payback from the pandemic in 2022, while in the US this should be the case already a year earlier. In China, we pencil in positive real GDP growth in 2020, followed by (somewhat mechanical) strengthening in 2021, and a return to a moderate deceleration in pace in the following years.

The uncertainty surrounding our economic outlook remains considerable. Hence, we maintain three scenarios: the baseline (a gradual recovery gaining traction from H2 2021 onwards), to which we attach a probability of 60%; the pessimistic (a disrupted and unsteady recovery) with the probability of 30%; and the optimistic (a sharp and strong recovery already in H1 2021) with a 10% probability.

Along with the start of the vaccination campaigns, the end of 2020 brought good news also with respect to the last-minute Brexit trade deal, and the new USD 900 billion fiscal package approved by the US Congress, both having posed notable downside risks to our baseline outlook earlier. Looking ahead, the evolution of the virus (with possible mutations as seen lately), as well as the pace of vaccination rollouts, not least possible disruptions to the distribution, remain the two most important risks to our economic outlook.

Signs of resilience in the euro area

The euro area finished last year in the grip of the virus. There are, however, encouraging signs of resilience in terms of the underlying growth dynamics. Industrial production rose both in October (2.3% mom) and November (2.5% mom), which owes something to a strengthening global recovery. However, on the retail side, the picture is more mixed. The expansion of 1.4% mom in October was followed by a sizable 6.1% mom drop in November, reflecting the tightening lockdown restrictions in most countries. This is visibly less than during the first wave of the pandemic (-10.2% mom in March 2020) but the headline figure masks large cross-country differences, such as a dramatic 18% mom drop in France.

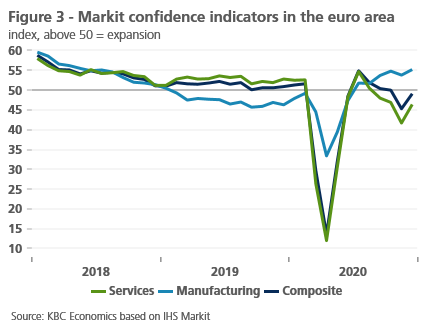

Sentiment indicators for December paint a rosier picture, suggesting better-than-expected activity was established by year-end. While having remained marginally below the 50-threshold marking the cut-off between growth and contraction, the euro area composite PMI data rebounded significantly ahead of expectations, driven by a particularly robust bounce-back in the services sector (figure 3). However, we interpret these figures with caution given the survey data was collected in the first half of December, gauging primarily the effect of the pre-Christmas loosening of containment measures in some countries.

What remains notable, yet less surprising is the ongoing gap between activity in manufacturing and the services sector. Unlike services, the industry remains largely unaffected by more targeted restrictions, and benefits from the supportive global backdrop, namely the strength of global goods demand originating in Asia. These positive effects contribute to the euro area resilience, despite the fact they are felt unevenly across the common bloc, favouring industry-oriented economies led by Germany and others highly integrated in the global manufacturing value chains.

All this points to a more moderate contraction in Q4 2020 than previously envisaged. Compared to the first wave of the pandemic, the fourth-quarter decline appears significantly less severe, partly owing also to the increased adaptability to ongoing lockdown measures on the side of consumers and firms. At the same time, our outlook for sluggish growth in Q1 2021 remains intact. If anything, the extended containment measures in Germany (end-January) or France (mid-February), including the closure on non-essential shops, have only reinforced our view in this respect. Looking past the near-term weakness, the major boost to economic activity from the vaccination, coupled with the first disbursements of the EUR 750 billion Next Generation EU, is expected in the latter part of the year.

Against the background of less negative growth in Q4 2020, we have slightly improved the euro area annual growth from -7.5% to -7.2% in 2020. For this year, we are pencilling in a somewhat stronger rebound of 3.1%, up from 2.4% previously. We project even higher real GDP growth of 4.2% in 2022 when a major payback from pandemic should take place (in terms of the annual growth rate). Consistent with our updated forecast, the euro area should reach the pre-pandemic level of activity in late 2022, earlier than mid-2023 initially projected.

A good but not great Brexit deal

A ‘last minute’ trade deal between the EU and UK was finally agreed in late December, long after multiple deadlines had been missed (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 12 January). The most important point is that a deal was reached, avoiding a ‘cliff edge’ outcome and the additional economic dislocation from the sudden imposition of tariffs and other major impediments at a point when European economies are already facing severe challenges.

Even with the trade deal just reached, there will be significant friction in goods trade between the UK and EU reflecting a substantially increased administrative burden of documentation and regulatory checks (see box 1: Brexit: What are the key points of the deal?). In addition, the UK’s position as a leading exporter of services has been undermined by restrictions and uncertainty around its access to the EU marketplace. Finally, broader uncertainty around the future path a more ‘independent’ UK economy might take is likely to diminish its attractiveness as a gateway for foreign direct investment and could also act as a constraining factor on domestic business capital spending.

Box 1 - Brexit: What are the key points of the deal?

The text of The ‘EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Agreement’ runs to 1246 pages-not including additional political declarations. In this box, we attempt to describe some of the key features of the deal rather than a comprehensive description of all of its elements.

The agreement reached between the EU and UK, while wide-ranging, is far from comprehensive and implies a marked change in the nature of relations between the EU and UK. The agreement is primarily focussed on ensuring tariff and quota free trade in goods. It also includes measures to facilitate continued strong aviation and road transport links, significant co-operation in areas such as energy, law enforcement and the provision of social security as well as providing for processes to support trade in services. On the vexed issue of fisheries, the deal provides for a phased reduction of 25% of EU catches in UK waters over the next five years.

Zero tariffs and zero quotas will apply to all goods traded between EU and UK provided those goods meet standard ‘rules of origin requirements’ which seeks to ensure that goods are not being produced in third countries. For example, at least 55% of the value of petrol cars should be attributable to the EU or UK or else a 10% tariff applies. A phased implementation allows a somewhat smaller proportion of value added in respect of electric cars in coming years.

However, while trade in good will be tariff free, it should be emphasised that the imposition of customs formalities, regulatory and health checks mean trade between the EU and UK will entail a notable burden of documentation and other frictions that are absent in trade within the EU. The UK’s decision not to fully operate customs checks for six months and a range of temporary concessions by both sides, such as a twelve month grace period before ‘rules of origin’ documentation is required, will provide some limited offset in the very short term.

Although the agreement envisages ‘a significant level of openness’ in trade in services, UK service producers lose their automatic right to supply their services across the EU and vice versa. Piecemeal and temporary measures including upcoming talks on the prospect of ‘equivalence’ approval for some financial services activities point towards notably more restricted and uncertain access for UK firms to the EU marketplace for services.

To underpin a healthy trading relationship, the agreement requires that both sides commit to a ’robust level playing field’ entailing standards in relation to the environment and climate change, social and labour rights and, critically, State aid. Where unfair actions by one party are deemed to have a material impact on trade or investment, a range of mechanisms allow for dispute resolution including some constrained scope for retaliatory actions.

The deal itself can be terminated by either side at any time once twelve months’ notice is given. Moreover, a full review of the agreement is to be undertaken in 2025 and every five years thereafter. There will also be ongoing assessments of various aspects of the relationship including an annual consultation on fisheries and, as well as regular reviews, a potentially significant vote in Northern Ireland on the Northern Ireland protocol in 2024. So, while the deal takes away short-term cliff-edge risks, Brexit will remain a source of uncertainty and difficulty for many European businesses for the foreseeable future.

In turn, these difficulties will spill over into poorer market growth for the UK’s key EU trading partners at a particularly inopportune time. The UK’s decision not to fully operate customs checks for six months and a range of temporary concessions by both sides, such as a twelve-month grace period before ‘rules of origin’ documentation, will provide a very limited offset. Similarly, there may be some partial compensation in time with the expected migration of FDI from the UK to other European countries. The adverse impact on euro area GDP is likely to be modest, particularly in comparison to the trauma resulting from the coronavirus. However, the reality is that more difficult access to a UK market that will be notably weaker than if Brexit had not occurred will be problematic for many European businesses in the year ahead.

Overall, we think there is much to be grateful for that a trade deal between the EU and UK has been agreed, as it avoids a no deal deterioration in trade prospects and the risk of further damaging ‘tit for tat’ measures along the lines of US-China tensions in recent years. However, the limited nature of the deal reached means that the Brexit story is far from finished and remaining risks highlight the fragile nature of international economic relations at present.

The US economy weathers the Covid-19 storm

The US started 2021 with a record surge in daily Covid-19 cases. But unlike in the euro area, few containment measures such as business closures or stay-at-home orders are in place. The impact on mobility consequently appears modest compared to the first wave of the pandemic, though somewhat blurred by Christmas holidays. While we do not expect the new US administration to introduce spring-like nation-wide lockdown, an elevated number of new cases, hospitalisation rates and death tolls may nonetheless may weigh on the pace of the recovery.

In the meantime, most recent high frequency data suggest that the US economy remains resilient, albeit the underlying picture is more mixed compared to a month ago. Retail sales, for example, showed a strong ongoing expansion on a year-on-year basis, but posted a drop of 1.1% mom in November. On the other hand, the major business sentiment indicators remained well entrenched in expansion territory in December. Although manufacturing is less important for the services-driven US economy, activity in this sector, in particular, surprised to the upside, indicating a robust expansion.

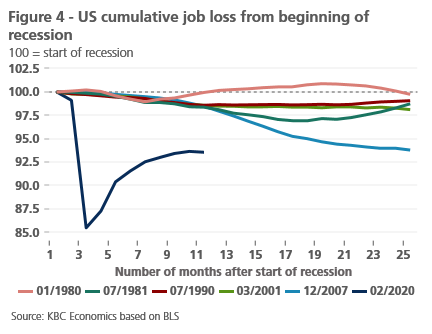

Finally, labour market data showed that recent gains, albeit decelerating, came to a halt in December. In contrast to expectations, the US economy lost 140,000 jobs, the first outright monthly decline in jobs since April 2020. Looking beyond the headline figure, the leisure and hospitality sectors were hit particularly hard, suggesting that the rapid spread of Covid-19 weighed heavily on the labour market. While we do not draw too strong a conclusion from the weaker-than-expected December jobs report, it highlights the challenging path to further recovery when the extent of the labour market damage is unlike in any other recession (figure 4).

On the bright side, after months of negotiations, the US Congress agreed on the comprise USD 900 billion (approximately 4% of GDP) fiscal package to provide additional pandemic support to households and businesses. This should help the economy to bridge the period before the positive effects of the widespread vaccination materialise. Furthermore, another round of fiscal stimulus is on the table as a consequence of a ‘blue wave’, with Democrats having the majority in both the House and the Senate following the runoff elections in Georgia (see box 2: US politics: turbulence but no gridlock).

Box 2 – US politics: turbulence but no gridlock

The sixth of January 2021 should have been a day that provided more clarity on the US political landscape. By winning both seats in the Senate runoff elections in Georgia, the Democrats secured a slim majority in both chambers of Congress (the Democrats now hold 50 out of 100 Senate seats, but Vice President-elect Kamala Harris will hold the power to break tie votes). Thus, President-elect Joe Biden will have some leeway to pass his agenda, but passage of sweeping reforms may still be complicated. This is especially true if the Senate filibuster remains in place - a rule that allows lawmakers to delay a vote on legislation unless 60 senators vote to move ahead.

The outcome of the Georgia election, however, was overshadowed by the events that transpired during Congress’s certification of the presidential election results. Though this certification should have also provided more clarity on the US political landscape (by putting an end to Trump’s attempts to contest the election), the storming of the capitol building by Trump supporters has thrown US politics into a new state of disarray. Many White House officials have resigned, the House has impeached Trump (again), and the Justice Department has said it would not rule out pursuing charges against Trump for his possible role in the event. As of now, it is not clear if these developments will drive a deeper wedge between the two political parties. Though there is near universal condemnation of the breach itself, there is not universal agreement on who is responsible or what is the best way to move forward.

Hence, Biden is faced with no easy task when he takes over on 20 January. Aside from a tenuous political situation, the United States is seeing a continuous rise in daily Coronavirus cases and deaths, and the economic recovery, though expected to continue, remains somewhat fragile, with a loss of 140,000 jobs in December. Fortunately, the passage of a new USD 900 bn stimulus package (4% of GDP) in December extended two programs that enhance unemployment benefits. The programs were set to expire at the end of the year but will now be extended by eleven weeks. This includes the expansion of jobless benefits to self-employed and gig-type workers among others, and the funding of additional weeks of unemployment benefits after regular state benefits are exhausted. The new stimulus package also adds an additional USD 300 to weekly unemployment benefits through 14 March, which is half the amount that was provided in the CARES act through July 2020. Beyond unemployment benefits, the new package also includes USD 600 checks for individuals making USD 75,000 or less per year, reopens the Paycheck Protection program for small businesses, extends the period for the deferment of payroll taxes, and provides funding for various groups, such as theaters and venues, schools and child care services, and hospitals.

Democrats are expected to pursue further stimulus after Biden takes control at the end of January. The ambition for such a package would likely include additional checks to individuals, an extension of the unemployment packages beyond March, and aid for states and local governments (a sticking point during the last round of negotiations, with Republicans firmly opposed). Negotiations, even among Democrats, may still be necessary, however, and arguments against further deficit spending will likely reemerge from Republicans now that the Democrats are in power. Thus, though the Democratic sweep suggests political gridlock can be avoided, US political waters will be far from smooth sailing in the short term.

All in all, our economic outlook for the US has been marginally improved to -3.5% (from -3.6%) in 2020 and to 4.4% (from 4.2%) in 2021 on the back of the upgrade of Q4 2020 real GDP growth. A further upward revision to the 2021 outlook may be warranted, particularly if more aggressive fiscal spending under Biden’s administration materialises. We project that the US economy will reach the pre-crisis level of activity already in 2021. The economic expansion is then set to moderate to 2.5% in 2022 but remaining above the long-term potential growth.

China’s economic recovery stays on track

The recovery in China continues amid some normalisation in the pace of economic growth following the strong rebound in the second half of 2020. Year-on-year industrial production growth roughly stabilised around 7.0% in the three months from September through November. Meanwhile, retail trade continued to catch up, accelerating to 5.0% yoy in November from 4.3% yoy in October. At the same time, business sentiment surveys on both the manufacturing and services side dipped slightly in December. However, both indicators remain well above the level that indicates expansion.

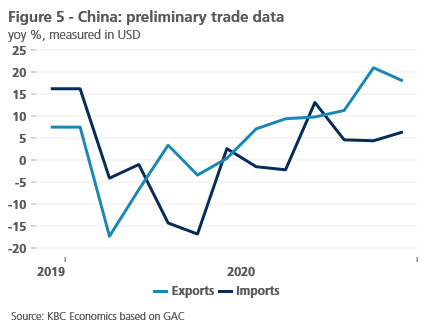

External trade data, particularly on the export side, also suggest that the recovery continues, with exports (measured in USD) growing 18.1% yoy in December. The recovery in exports has outpaced the recovery in imports, which may be reflective of the two-speed nature of China’s domestic recovery, with investment and industrial production leading the way while consumption and retail sales lagged behind. However, just as we have seen the consumption side of the economy start to catch up in recent months, Chinese imports are also recovering, and grew 6.5% yoy (measured in USD) in December (figure 5).

As a result, China has already recovered above the pre-pandemic level of activity. We are pencilling in positive annual real GDP growth of 2.1% in 2020, a stark contrast to major advanced economies. This year, we expect the Chinese economy to expand a strong, but somewhat mechanical, 8.5%, followed by a more moderate, yet still robust, 5.2% in 2022 as the long-term structural slowdown of the Chinese economy continues.

The strong recovery in China, along with long-standing structural issues, may present a policy dilemma for the Chinese central bank (PBoC). On the one hand, the relatively swift recovery of the Chinese economy and limited monetary easing in 2020 has led to a strong appreciation of the RMB versus the USD since end-May (roughly 10%). At the same time, inflation in China has trended down steadily the past several months, and even dipped into deflation territory in November (-0.5% yoy). Most of this was led by a normalisation in food prices, which should fade out in the next few months. Core inflation, however, has also declined (to a lesser extent) and the strength of the RMB may continue to weigh on inflation in 2021.

The expectation for further policy easing is nonetheless limited. Credit risks in the Chinese economy remain high, particularly for highly indebted state-owned enterprises and in the real estate market. With these risks lingering, and the economic recovery expected to continue in 2021, the PBoC is likely to remain on hold in the medium term and rely instead on more targeted tools to address the appreciation of the RMB.

Monetary policy to support a post-pandemic recovery

Major central banks made an extraordinary effort to mitigate pandemic-related financial strains last year. Importantly, since the onset of the pandemic, a highly accommodative monetary policy stance has been coupled with a sizable fiscal expansion. This has resulted in a strong synchronised macroeconomic policy response, contrasting with the earlier experience during the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Given the unprecedented nature and size of the pandemic shock, we assume that the current accommodative monetary policy stance will remain unchanged on both sides of the Atlantic until at least the end of 2022, maintaining favourable financial conditions and supporting a sustained post-pandemic recovery.

In the euro area, the ECB extended its monetary policy support further in December. As widely expected, the Governing Council increased the pandemic emergency purchase programme by EUR 500 billion to EUR 1.85 trillion, while extending the horizon of net purchases by nine months until March 2022. Furthermore, the recalibration of its policy instruments encompassed additional support via targeted long-term refinancing operations with a twelve month extension of more favourable conditions until June 2022. The key policy rates were left unchanged, as well as the forward guidance envisaging rates at current or lower levels until the inflation outlook has improved sufficiently.

Consistent with our inflation outlook, we expect the ECB to maintain policy rates at the current level at least through the end of 2022. In December, euro area headline inflation stood at -0.3%, resulting in marginally positive average annual inflation of 0.3% in 2020. The near-term inflation outlook remains clouded by a host of one-off factors (e.g. the expiry of the German VAT reduction or the delay of the sales season in France), as well as uncertain virus dynamics. In our view, inflation should pick up from the recent lows, primarily due to the energy price base effects. The underlying price pressures are, however, set to remain muted, owing to both cyclical influences and structural disinflationary forces. Overall, we expect inflation in the euro area to reach 1.0% in 2021, and 1.3% in 2022, implying (at least) another two years of undershooting the inflation target.

Similarly to the ECB, we expect the Fed to maintain its policy support and keep the funds rate at the current effective lower bound thought at least 2022. At its December meeting, the FOMC kept the monthly asset purchases unchanged, i.e. at least USD 80 billion in Treasuries and USD 40 billion in agency mortgage-backed securities, but adjusted the related forward guidance, linking the timeframe for purchases to dual mandate objectives. Together with the most recent comments and speeches, this step suggests that maximum employment has taken precedence over the price stability goal.

Meanwhile, the US inflation dynamics have remained relatively stable over the course of the pandemic. Following headline inflation of 1.3% in 2020, we forecast a rise to 2.0% in 2021 and 2.1% in 2022 with risks tilted to the upside, particularly given the possibility of a more aggressive fiscal stimulus under Biden’s administration. This would imply a moderate overshooting the 2.0% inflation target, something the policymakers signal to tolerate for some time to compensate for the earlier period of lower inflation. An effort to close the ‘inflation gap’ under the new policy framework of inflation targeting is nonetheless clouded by several unknowns and it remains to be seen what all this will mean in practice.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up to date, up to and including 11 January 2021, unless otherwise stated. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 11 January 2021.