Is services inflation still persistent in the US?

- Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Much ink has already been spilled about inflation, from different angles inflation has been analyzed and judged whether or not central banks should already ease their monetary policy.

In this article, we discuss the persistence of inflation. For different categories of the US Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE), we look at how persistent both demand and supply shocks are. This distinction is important, after all, when a negative supply shock hits the economy, inflation rises but growth falls. Thus, a central bank is more likely to fight inflation, and try to cool the economy, when it is driven by a positive demand shock than by a negative supply shock. It is also important for a central bank to know whether these shocks are persistent. When positive and negative demand shocks alternate, there is less need for a central bank to intervene each time. When these shocks turn out to be persistent, this means additional information for a central bank in its interest rate decision. We note that both positive demand shocks and negative supply shocks have been extremely persistent in recent years, although the situation in many PCE components has already normalized, service inflation remained persistent. It is services inflation that is being watched with suspicion by financial markets and central banks. The fear of rising wages, which constitutes a large part of service inflation, is making central banks reluctant to ease monetary policy.

Persistency of supply and demand

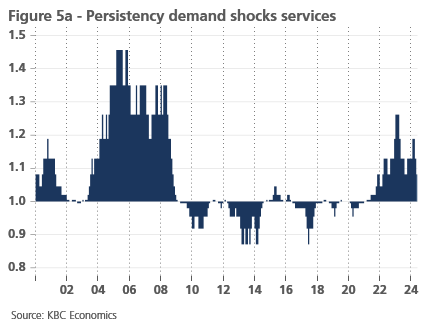

To measure the persistence of demand- and supply-driven inflation, we build on the work of Sheremirov (2023)1]. In the proposed method, the demand or supply shocks calculated in Shapiro (2022)2 are defined as persistent when these shocks occur above average. One expects the same amount of demand and supply shocks and the more one deviates from this expectation, the more persistent one catalogs the demand or supply shocks. In this article, we do not use Shapiro's method to identify supply and demand shocks, but use a Bayesian structural vector autoregression (SVAR) model, in which we calculate shocks based on sign restrictions. Since in this method demand and supply shocks can occur simultaneously for each inflation component, we modify the definition of persistence. As a basic assumption, we state that under normal conditions, positive demand or supply shocks occur as frequently as negative ones. This assumption also allows us to distinguish between persistent negative and positive shocks. We quantify deviations from this basic assumption for both demand and supply shocks using Shannon entropy3. For the goods, services and food component of PCE inflation, we first calculate the demand and supply shocks, then measure how random the negative and positive demand and supply shocks are.

Has the persistence of services inflation passed its peak?

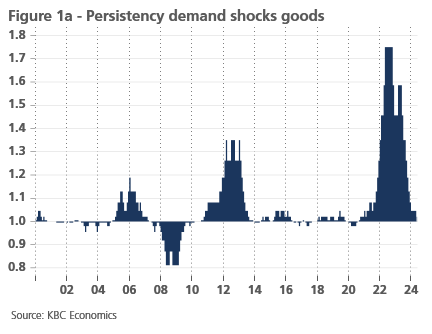

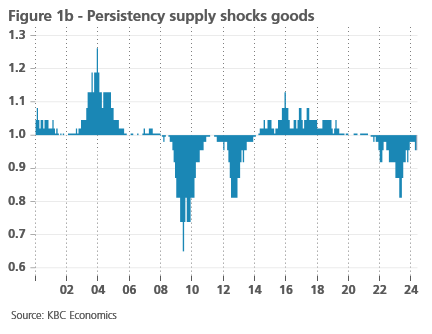

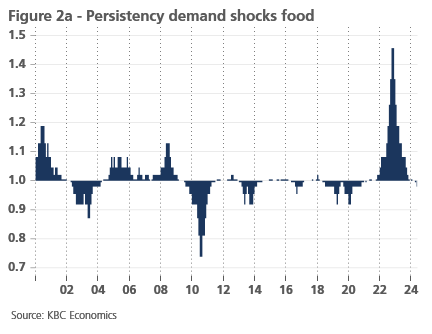

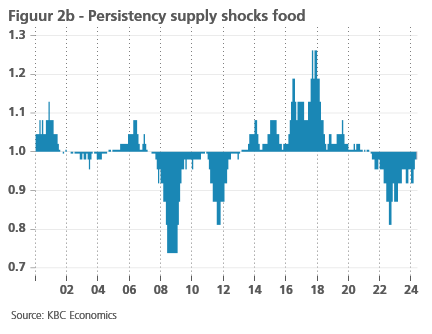

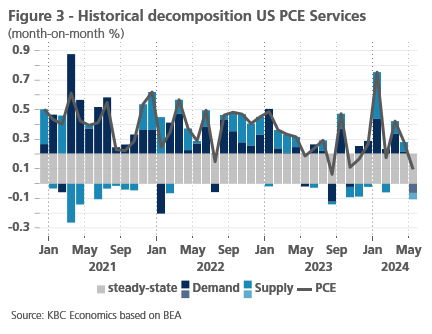

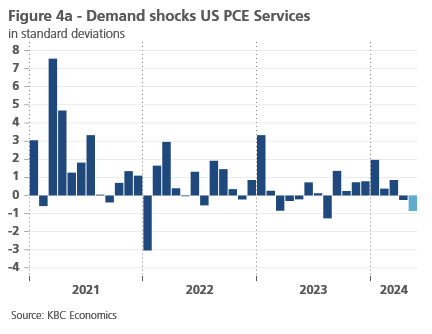

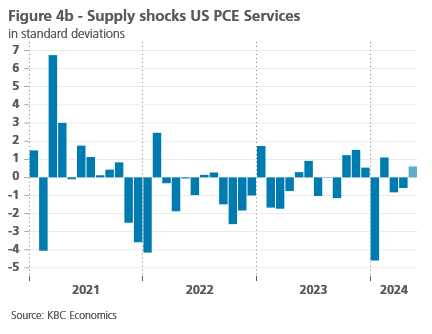

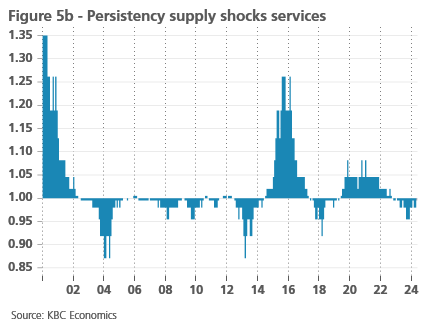

For most product categories we observe persistence in the negative supply shocks and especially in the positive demand shocks. Depending on the time interval over which we consider the randomness of the demand and supply shocks, the highly non-random shocks of 2021 and 2022 continue to weigh on the persistence value for 2023. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the persistence of PCE inflation for goods and food, which seems to be behind us. When positive and negative shocks occur randomly, we give persistence a value of 1. If positive shocks become persistent, the value is greater than one, and the opposite is valid for the persistence of negative shocks.

However, this story does not apply to services inflation. The supply shocks that have hit the services sector in recent years do not appear to be persistent (Figure 5). There is persistence on the demand side, however, and it increases again in 2024. While the lack of randomness of demand shocks remains lower than we observe in other inflation categories, it has fuelled fears of a wage-price spiral or over-optimism in the US economy. However, the April and especially the May data have allayed some of these fears. The decline in month-on-month growth in services is partly due to a negative demand shock, which also lowers the persistence metric.

A behavioural perspective

Are persistent demand shocks a problem? From a behavioural perspective, economic agents may come to regard certain shocks as the new normal. For example, a consumer or a firm may mistakenly expect that after a positive demand shock the economy will continue to perform at that high level, so the agent adjusts its behaviour and creates a new demand shock. For example, more is consumed or more people are hired than the agent's future economic situation will allow. Thus, non-random positive demand shocks can reflect a bubble in the economy. This can lead to (large) negative demand shocks in the future. Should we fear such a scenario after a period of historically high persistence of mainly positive demand shocks?

Persistency, what’s in a name?

Persistence can have several causes. In the methodology used, atypical shocks may have a different path from the average supply and demand shock. These are then misinterpreted as new shocks in the following months. However, as far as positive demand shocks are concerned, our focus for the post-covid period is more on the post-covid excess savings, partly caused by positive fiscal stimuli. These allowed for strong consumption and continued economic growth despite the persistence of adverse supply shocks. In other words, the persistence of demand served to counteract the persistence of supply. Now that the savings buffers have been largely depleted, it is hoped that economic agents will be able to continue their behaviour, as not only the savings buffers but also the adverse supply shocks should be off the hook.

Conclusion

Inflation in recent years has been extremely persistent in its various components. This has been the case both on the supply side and, in particular, on the demand side. It is fuelling fears of excessive optimism in the economy, although we point mainly to excess savings and fiscal policy. Nevertheless, it has contributed to central banks raising their policy rates dramatically. The persistence in the food and goods sectors is already behind us, but the continued, albeit limited, persistence in the services sector this year is keeping the Fed and the financial markets on their toes. Nevertheless, negative demand shocks in April and especially May in the services sector are taking some of the fears away.

1 Sheremirov, Viacheslav. "Are the Demand and Supply Channels of Inflation Persistent? Evidence from a Novel Decomposition of PCE Inflation." Evidence from a Novel Decomposition of PCE Inflation (November, 2022). Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Paper Series Current Policy Perspectives Paper 94983 (2022).

2 Shapiro, Adam Hale. "How much do supply and demand drive inflation?." FRBSF Economic Letter 15 (2022): 1-6.

3 H(X) = -∑2(i=1) p(xi) * log2(p(xi))