Slovak parliamentary elections

Slovak parliamentary elections

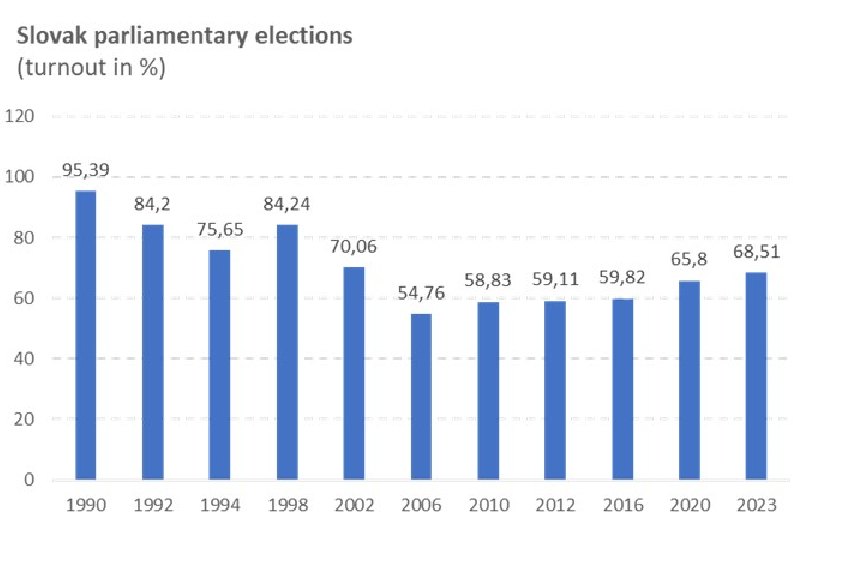

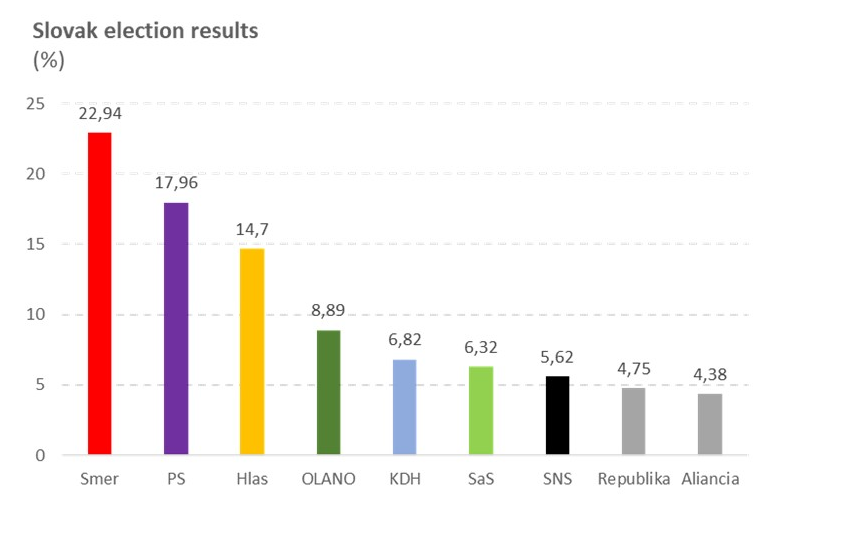

End of September, Slovakia held early parliamentary elections. The pro-EU government had previously collapsed after the rising coalition tensions because of chaotic domestic governance and pandemic crisis. The rising popularity of the more and more anti-systemic Smer party (defining itself as ’social democrats’) led to a unsurprising win for those forces. However, the result is not so dominant as in the past. Smer (’Direction’) is led by the experienced populist and former prime minister (3 times) Robert Fico. He led his party with his gradually more populistic antisystem rhetoric to victory in the elections with 22.94% of the vote. That still is the third worst result of the party’s history but with rising turnout it is more difficult to get a higher result (see figure).

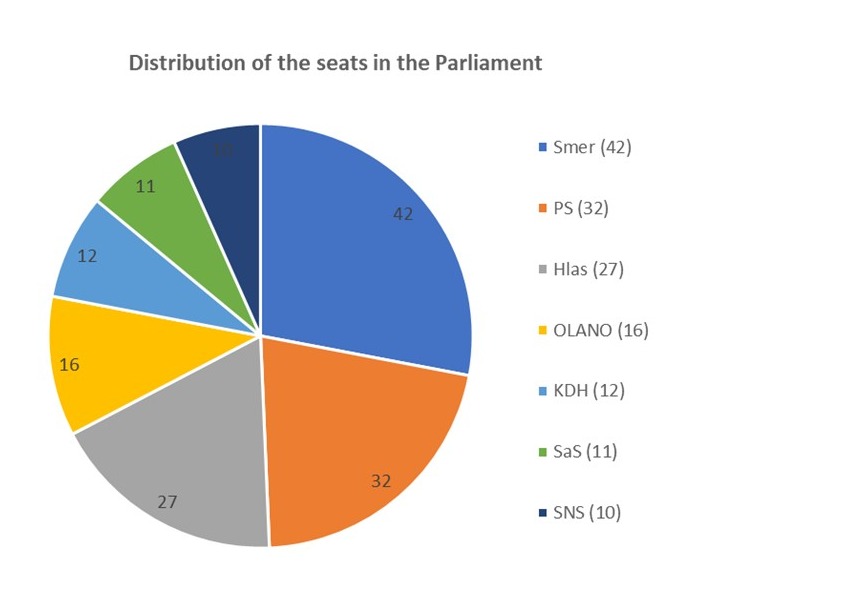

Moreover, the Smer party split approximately 3 years ago into Smer and a new party Hlas (’Voice’), led by the former PM Peter Pellegrini and long-standing companion of Robert Fico. Both parties define themselves as left-wing or socialist parties, focusing on the role of a strong and social state particularly in regards to pensioners and subsidies to the economy. Hlas party (14.70%) is the potential coalition partner of Smer (despite probable personal animosities between both leaders) and is now the third biggest party behind the new pro-EU party Progresívne Slovensko (PS). PS is led by the new young leader Michal Šimečka, currently the deputy president of the EU-parliament (the first Slovak in history). PS is a pro-EU centrist progressive party emphasising economic, social, European, environmental and climate change topics (to mention some of them). PS is the main challenger and a major critic of the Smer party, which has been tainted by corruption scandals. PS obtained the second place in the election race with 17.96%, the best result in its history. Last elections (3.5 years ago), PS did not get clear the 7% parliamentary threshold and thus stayed out of parliament. The fourth party is OLANO (8.89%) whose leader and former PM Igor Matovič is known for his mismanagement of the pandemic crisis. OLANO already signalled that it will stay in opposition and will focus on anti-corruption topics. The last three parties are the Christian-democrats from KDH (6.82%), liberals from SaS (6.32%) and the nationalists from SNS (5.62%).

The preferred coalition of Smer leader Fico is Smer+Hlas+SNS, holding altogether 79 seats in the 150 seats parliament (see figure). This is a thin majority. Moreover, for the SNS party, only one seat is held by an original SNS party member (its leader Mr Andrej Danko). All 9 other seats are distributed to non-party members. They were candidates on the list of the SNS and were elected through the election system of voters-marking selection (putting higher preference for certain candidates). Therefore, it is not clear how aligned the parliamentary members are with the leader on key party policy topics.

Some observers point to alternative scenarios of a wider four-member coalition of Smer+Hlas+SNS+KDH (91 seats) or a Smer+Hlas+KDH coalition (81 seats). The first one has a constitutional majority (91/150) but is possibly less stable as there more parties involved and the second has a comfortable simple majority (5 seats above 76 threshold). KDH declared during the campaign that it will not rule with Smer. However, its leader did not rule out possible roundtable non-obligatory talks. He emphasized that it is not the party management deciding but the Council of the KDH party (the regional party leaders structure), which is scheduled for 14 October. Therefore, this option cannot be ruled out. On the other hand, at least two-party members publicly explained they will not personally support a coalition with Smer, theoretically leading to the loss of two MPs. The winner of the election (Smer party) was the first to obtain a mandate to form a government on Monday (limited to two weeks). If unsuccessful, PS leader Šimečka will have the initiative with a probable intention to form PS+Hlas+KDH+SaS coalition, theoretically holding 82 seats. This is not the preferred option of the Hlas party and possible tensions between liberals and conservative Christian democrats are another possible complication. Therefore, Peter Pellegrini and his Hlas party will have the king-making role in forming the government and Smer leader Fico will get the chance to lead the new the ruling coalition as leader of the largest party (see figure).

What could a Smer+Hlas+SNS coalition mean for the economy? This is the first time that Smer will rule the country in tough economic conditions. The country needs to implement the consolidation package, designed by the care-taking government of the well-known economist and former vice-governor of central bank Ludovít Ódor. It is possible to implement it with some variability in measures but the new coalition will need to target 0.75 – 1.00 ppt of GDP of annual budgetary consolidation during the next four years. This is in the current environment of weaker external economic environment, persistent risks (e.g. escalation of the war in neighbouring Ukraine) and significantly higher interest rates. If it fails to consolidate its budget, the government bond spreads could rise, making loans more expensive . The rating agencies signalled some time ago that fiscal consolidation is the key pre-condition to keep the current rating status (S&P “A+ stable”, Moodys “A2 negative”, Fitch “A negative”). The main challenges are the economic environment, public finances, the green transition of the economically important car and other industries and higher inflation impacting household consumption. The country has already diversified energy import (gas), through cooperation in nuclear energy production (agreement with Swedish-U.S. Westinghouse and memorandum with French Framatome) and through new investments for diversification/processing in the oil industry. In combination with diversified gas import contracts and almost full gas storage, this would make Slovakia much less fragile to future energy crises.

The economic policy of the new government will be under scrutiny. The Smer party could significantly shape the new economic policy as a potential coalition leader. What could this mean? Looking back into history and at the current the rhetoric, the main concern could come from fiscal policy and public procurement (and fair public tenders). The potential risk is that the fiscal consolidation could be too slow or that public procurement could be less transparent. Smer, for example, advocated for the abolition of the public procurement office and for limited fiscal consolidation. This could prompt the European Commission to slow down, interrupt or stop the flow of EU money. The importance of EU money in public investments is obvious and its interruption would be challenging. If Smer is able to form the new coalition, it will be confronted with a tough economic reality, jittery financial markets, hostile foreign partners (e.g. EU) and difficult demands of its potential coalition partners. The Hlas already softened the rhetoric against the defence support for Ukraine by proposing to allow arm exports on a commercial basis (e.g. ammunition export). Hlas also softened its rhetoric against EU/NATO partners and will possibly be a more pliant partner in the potential new coalition, than initially expected.