Climate Scenarios Not Quite There Yet

The climate crisis is rife with uncertainty. Mapping out possible climate pathways is inextricably linked with important unknowns such as future policy developments, technological progress, behavioral change, and difficult-to-model tipping points. On top of this, estimating the impact that different potential climate pathways could have on the macroeconomy requires complex and innovative modeling techniques. The work done by the Network for Greening the Financial Sector (NGFS) to develop detailed climate scenarios that can be used by policymakers, supervisors and the private sector is, therefore, hugely beneficial for advancing our understanding of risks and opportunities posed by the climate challenge. However, there is still clearly more that needs to be done, particularly to avoid counterproductive messaging on the severity of the crisis and the need to act sooner rather than later.

The NGFS, a consortium of central banks and supervisory bodies working to develop “environment and climate risk management in the financial sector” and to mobilize green finance for a sustainable economy, released the first iteration of their climate scenarios in 2020. There have been three updates since then, with the latest being made public in late 2023 (also known as Phase IV). While the highlighted updates have a clear reasoning behind them, such as reducing reliance on carbon capture technologies, and incorporating setbacks to the energy transition that resulted from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Phase IV scenarios also lead, perhaps unintentionally, to some blurred policy messages.

NGFS design: matrix of transition and physical risks

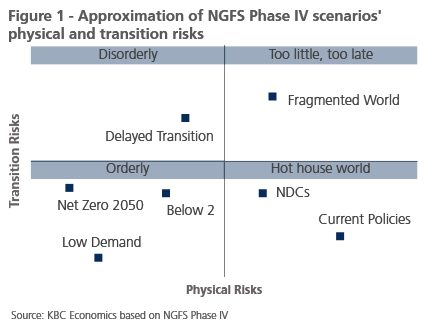

For background information, the NGFS classifies its various scenarios in a quadrant system, defined on one axis by transition risks, and on the other by physical risks. Scenarios are then either classified as orderly (low transition risks and low physical risks), disorderly (low/limited physical risks but high transition risks), hot house world (low transition risks but high physical risks), or too little too late (high transition risks and high physical risks) (figure 1). While it is intuitively clear that policymakers should strive to avoid the scenarios with high physical risks (i.e., where global policy is not enough to limit temperature increases), the argument for the orderly over disorderly scenarios has always been twofold: (1) implementing climate policies sooner rather than later allows for a smoother transition that ultimately limits (cumulated) costs, and (2) an orderly transition is the best bet for actually achieving Paris Agreement temperature targets (rather than overshooting) and likely the only way to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Net Zero becomes less orderly...

In Phase IV, Net Zero has moved up the transition risk scale toward the disorderly quadrant given delayed progress on climate policies and emissions reduction. This is captured by a much higher shadow carbon price (i.e. more stringent policy measures) now needed to reach Net Zero. This is a key message to send to policymakers; we have, barring some major technological breakthrough or significant change in behavior, run out of time for implementing a fully smooth transition to Net Zero. Furthermore, the longer we wait, the more disorderly the transition will inevitably be.

... and sometimes even more expensive than waiting?

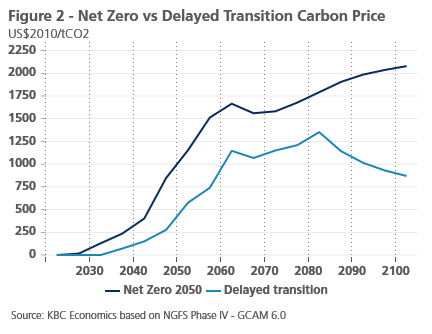

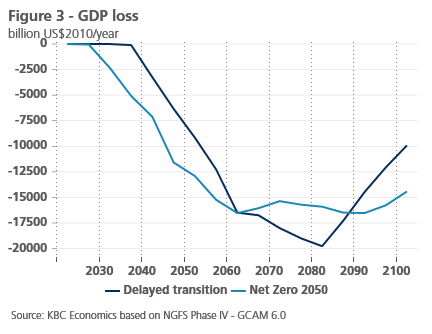

However, the change in scenario also inadvertently sends another message, which is that the Delayed Scenario, in which policy initiatives are initially limited and then increase drastically after 2030, requires a far lower carbon price than Net Zero, even in the longer term (figure 2). Furthermore, the policy cost difference between Net Zero and the Delayed Scenario as measured by GDP loss (estimated both through Integrated Assessment Models and the NIGEM economic model) is, over the long term, somewhat negligible, and even sometimes higher under Net Zero (figures 3 & 4).

The comparison with Net Zero is not entirely one-to-one. Global warming in the Delayed Scenario surpasses 1.5 degrees (averaging 1.67 degrees by the end of the century) and entails risks of overshooting 2 degrees of warming. Still, the message regarding the difference in policy costs is slightly problematic because policymakers need to balance transition costs with the physical costs associated with such temperature rises, and they might believe that the cost of an extra 0.17 degrees of warming isn’t worth the extra, frontloaded transition risk.

Room for further improvement

This is where modeling limitations become crucial; the true cost (economic or otherwise) of surpassing 1.5 degrees is not easily modeled. The NGFS even notes that while work has been done to add acute and chronic physical risk damages to estimates of GDP losses, these estimates are still incomplete.1 More importantly, the impact from reaching tipping points and triggering positive feedback loops for GHG emissions are not accounted for. The economic costs of the physical risks of climate change are therefore likely still significantly underestimated by these models. Since NGFS models are a major (and crucial) input for policymakers, regulators and financial institutions, these limitations, and their potentially counter-productive messages (at least at face value), are crucial to understand. Fortunately, the NGFS still continues to refine their modeling and scenario creation. But for now, uncertainty remains a major aspect of analyzing climate risk.

1 https://www.ngfs.net/ngfs-scenarios-portal/faq#macro-economic-impacts-from-climate-physical-risks