Innovation: a lifesaver for the European economy

Contents:

- Economic importance of innovation

- Measurement of innovation

- Complex process

- Innovation policy: a tangle with a European dimension

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF file.

Now that economic growth in some parts of the world has eased, the question of what the global economy can structurally improve resounds. Paul Romer, one of the Nobel Prize winners in Economics in 2018, is considered one of the founders of modern growth theory. Growth is achieved through a greater use of production factors, in particular labour and capital. Due to the increasing tightness in many labour markets and a reluctance in most of these countries to alter policies to improve participation rates or increase economic migration, activating a more intensive use of labour seems to be a difficult task. Recent upward wage movements are also gradually increasing the cost of labour. In addition, a greater use of capital - traditionally defined as the whole of business premises, factories, machinery and installations - is also subject to constraints. On the one hand, there are financial constraints, because corporate debt has increased considerably worldwide in recent years (also see: 'Debt quality, not accumulation, threatens financial stability'). On the other hand, additional investments in the capital stock are only meaningful if sufficient personnel can be recruited for the production process or business operations. The latter is not evident in a tight labour market. The main complaint of entrepreneurs today is that the increasing shortage of skilled employees limits the growth of their businesses. Therefore, we must seek macroeconomic salvation from another growth recipe, which was also emphasized by Paul Romer in his "endogenous growth theory", namely innovation or the creation of new technologies.

In the context of the fourth industrial revolution, where digital technologies are becoming increasingly important in production processes, innovation is one of the essential elements to ensure sustainable economic growth. Innovation is the driving force behind productivity growth and the launch of new products and services. With declining productivity growth in the Western world and increasing competition from emerging economies in a global market environment, innovation is rightly the necessary response of the West, and of Europe in particular, to these challenges. It is therefore difficult to overstate the importance of innovation for our economy.

Innovation is a broad and general concept that requires concrete implementation. The World Economic Forum (WEF) uses a number of principles to determine a country's innovative capacity. For example, a country's ability to innovate depends on the quality of a complex ecosystem. It is not enough for companies and research institutions to invest in research and development (R&D). After all, it is a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for innovation. Equally important is the conversion of R&D into successful products and services or into improving production or management processes. In other words, valorisation or actual implementation is crucial to create economic value from R&D activities. This is often where the shoe pinches. Many countries score relatively high in research activities, but fail to convert research results into new economic activities.

The degree to which a country is innovative is one of the components measured in the Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), the WEF measure that measures a country's competitiveness using twelve pillars. On the basis of the above principles, the WEF compiles two pillars that determine the score for the innovative ecosystem component. The first pillar comprises business dynamics, which include administrative procedures (cost and time of setting up a business, regulatory framework for insolvency, etc.) and business culture (attitude towards entrepreneurial risks, etc.). The other pillar gives a score on innovative capacity. Its subdivisions are: interaction and diversity (diversity of the workforce, international collaborations,...), research and development (R&D publications, patent applications,...) and commercialisation (trademark applications,...). In addition, other GCI components also play an important role in determining the extent to which a country is or can be innovative. These include the implementation of ICT applications, the quality of education, the intensity of competition and the availability of funding.

Based on the scores for the innovation capacity pillar (pillar 12 in the GCI), we see that the number of innovation hubs in the world is very limited. Only 4 out of 140 economies achieve a score above 80 out of 100 on the pillar, with 100 representing the ideal situation. Germany (87.5/100), the USA (86.5/100), Switzerland (82.1/100) and Taiwan (80.8/100) are at the top of the ranking, while Haiti (20.3/100), Congo (18.8/100) and Angola (16.8/100) are at the bottom. The global median score on the innovation capability pillar is only 36 out of 100, the lowest across the 12 pillars. Moreover, more than half of the countries studied score worst on this pillar.

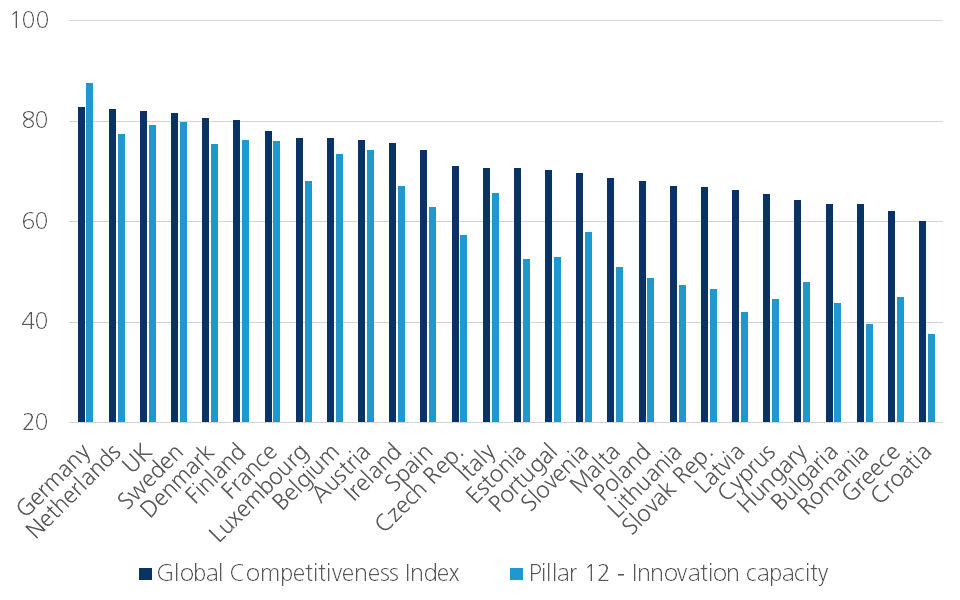

The situation within the European Union (EU) is similar. With the exception of Germany, the score on the innovation capacity pillar in all EU countries is lower than their overall score on the GCI (Figure A). Also immediately noticeable are the large differences between the European countries. (South) Eastern Europe still lacks basic infrastructure for innovation, which means that countries score weakly on the twelfth pillar, while their overall score on the GCI is much better. The absolute innovation frontrunner, on the other hand, is Germany. This strong German performance is due to good scores on patent applications, research publications, leading research institutions and relatively sophisticated customers, who constantly challenge companies to innovate. In addition, innovative companies can benefit from a favourable business environment to bring innovative products and services to the market. However, there is still room for improvement in Germany as well. Surprisingly, the country is lagging behind in ICT applications with a score of only 69.3 out of 100 (31st in the global ranking). Also the relatively low number of mobile Internet subscriptions and rather weak ICT infrastructure (e.g. internet cabling) require some catching up in Germany.

Figure A - Global Competitiveness Index scores (score out of 100)

With the exception of the four top innovators mentioned above, most countries perform poorly in terms of innovation. The WEF attributes this mainly to a lack of valorisation and explains this by the complexity of the innovation process. Innovation starts with ideas of which only a few develop into concrete inventions. In turn, not all inventions are commercialised either. Innovations stimulate economic and productivity growth only when they reach the market and are a commercial success. Any missing factor in the complex ecosystem - e.g. insufficient funding, hampering regulatory framework, etc. - is a key factor in the success of the project. - can cause new ideas not to become valuable commercial products.

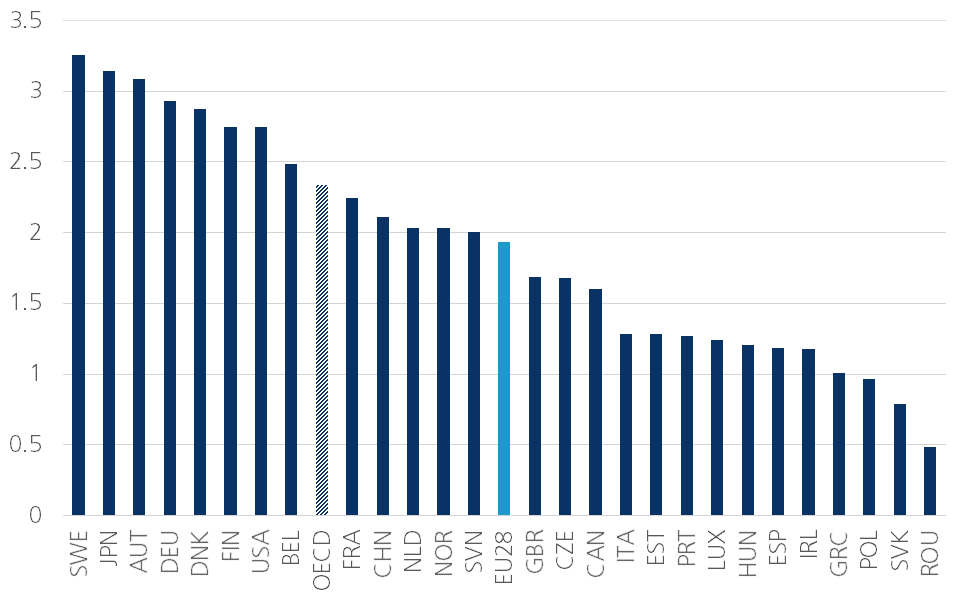

Because of the importance of innovation for economic development, innovation has traditionally been a part of a government’s policy agenda. This applies to both the national (and often also regional) and the international level. The European Union, in particular, has been a major driver of innovation in recent years. However, the institutional policy space around innovation for the EU remains very limited. Above all, the EU can create a general framework within which the EU Member States can design their own policies. In 2000, the European Commission launched the Lisbon objectives. The aim was to make the EU the most innovative region in the world. The recent WEF scores show that this task is still far from complete. The Lisbon objectives include a concrete focus on spending on research and development. These were to reach 3% of GDP in all EU Member States by 2010. This objective was not achieved at all, with a few exceptions. In 2010, the European Commission reiterated the same objective, albeit somewhat differently packaged, as the ‘Europe 2020 strategy’. The most recent state of affairs indicates that the objective has still not been achieved (Figure B). The 3% target is actually ad hoc, but was inspired at the time by the average R&D expenditure in other Western economies, in particular the United States and Japan. These countries did manage to maintain their R&D expenditure at that level. As a result, Europe's lag in terms of productivity growth, new technological sectors, etc. grew.

Figure B – Gross domestic spending on R&D (in % of GDP, 2016)

In addition to European targets for the level of R&D spending, Europe is committed to a general innovation-oriented policy. The focus here is strongly on valorisation, with a number of European initiatives being launched to increase cooperation between European companies and research institutions. The European funding programmes for innovation contribute to this by financing part of the research costs. The current Horizon 2020 programme focuses on strategic research themes that encourage collaboration between researchers from several Member States, as well as collaboration between businesses and universities. In particular, much attention is paid to the participation of SMEs in the entire process. Moreover, the focus is on the social contribution of each project. This programme makes a significant contribution to research and innovation in Europe, with a budget of around €80 billion over the period 2014-2020.

In a free market economy, innovation is primarily a market process. Only if there is sufficient economic return will companies be prepared to invest resources in research and development. Nevertheless, we note that public support at European and national level remains important in practice, especially in order to make up arrears. Funding for research, innovation and valorisation will be crucial in the future to prepare Europe for growing competition on the world market, as well as to mitigate the impact of social and demographic developments.