School leavers on their way to the labour market

A smooth match between the studies followed and the jobs on offer is generally considered crucial for a well-functioning labour market. In Flanders, this match has improved over the past two decades and the region scores well in a European perspective. While it is good that young people choose sufficiently for profession-specific education, it is also important that they acquire sufficient general skills to adapt flexibly in a rapidly changing economy and labour market. Moreover, due to demographic conditions, there will be job opportunities in almost all sectors and occupational groups in the coming years, which will make it easier for young people to choose a course of study or training they like.

After the pandemic, the labour market soon faced tight conditions again. Apart from delayed growth in the working-age population, it is also related to the phenomenon of mismatch between labour supply and demand. Indeed, despite numerous vacancies, there remains considerable unemployment. The mismatch between labour supply and demand is, in turn, a consequence of insufficient geographical mobility and a mismatch between labour supply and the profiles in demand on the labour market.

A good match between study choices and training supply on the one hand and employers’ labour demand on the other is one of the important factors in preventing mismatches. Horizontal mismatch occurs when too few young people choose studies that are well positioned in the market. Vertical mismatch means that graduates have insufficient or not the right knowledge and skills to get a good start in the profession for which they have been trained (e.g. with outdated training programmes). These mismatches are undesirable both economically and from the individual perspective of the graduate. They lead to a loss of return on educational investment because knowledge is not (fully) utilised in the labour market. Macroeconomically, underutilisation causes higher overall unemployment or underproductivity of workers. At the individual level, there are higher risks of (long-term) unemployment, lower wages or job dissatisfaction. This plays out in the short but also in the longer term, as the labour market position of young people at the start of their careers often determines their later careers (‘scar effects’).

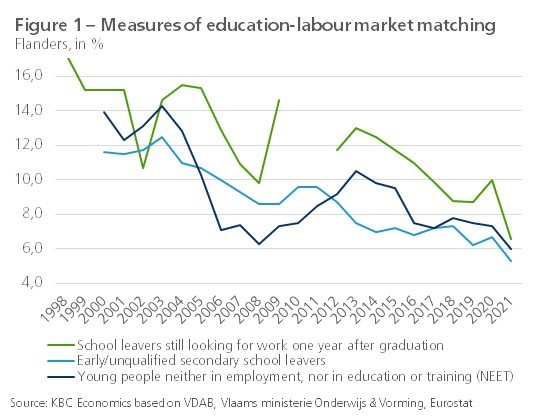

Figure 1 shows three measures that paint a picture of how smoothly young people progressed into the labour market over the past two decades: (1) the share of school leavers who are still registered as unemployed jobseekers one year after graduation (source: VDAB annual School Leavers Report), (2) the share of young people (18-24 years old) who left secondary education early and unqualified (source: Flemish Ministry of Education and Training) and (3) the share of young people (15-24 years old) who are neither employed nor in education or training (so-called NEETs, source: Eurostat). The figures refer to Flanders because, for the first measure, figures are only available for that region.

The figure shows that the connection between education and the labour market in Flanders has improved on a trend basis since 2000. There were fluctuations in the successive figures, but these had much to do with the economic cycle and the corresponding slowdown or acceleration in the job market. Specifically, the situation worsened during the dotcom crisis, the financial and debt crisis, and the corona pandemic. In periods of economic crisis, young people are usually the first to share in the blows. Belgium as a whole scores worse than Flanders for the latter two measures, but better than the EU average. The unqualified outflow of young people was 6.7% in Belgium in 2021, compared to 9.7% in the EU. Belgium’s NEETs rate was 7.4% in the same year, compared to 10.8% in the EU. The better Flemish figures (5.3% and 6.0% respectively) were more in line with those of the Netherlands (5.3% and 5.1% respectively).

The trend improvement has several causes. More recently, since 2016, increasing labour market tightness plays a role. Due to the rising vacancy rate, job opportunities for school leavers were higher than ever. There is also the increased participation in higher education. The VDAB’s annual School Leavers Report shows that the more highly educated the school leaver is, the lower the chance of still job-searching after a year. Among school leavers with a higher diploma, only some 2% were still looking for work after one year. Finally, young people are also increasingly making study choices focused on the labour market (including STEM and care studies), partly due to better study guidance and cooperation between education and the professional field.

Profession-specific or general?

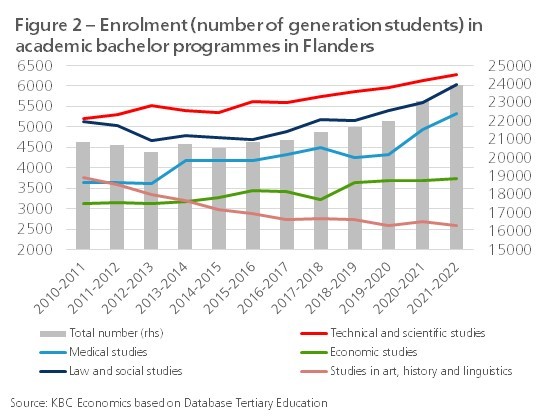

It is important that the improvement continues in the coming years. After all, the Federal Planning Bureau expects the working-age population to start declining from 2024 onwards, threatening to make the labour market squeeze even more acute. That is why it is essential that young people continue to opt sufficiently for education with a profession-specific slant. Especially in those labour market-oriented courses, professional competences should be included in the curriculum as much as possible and updated on a regular basis. The business sector can contribute by providing sufficient workplace learning capacity, access to their (high-tech) infrastructure and opportunities for the professionalisation of teachers and lecturers. In academic higher education, too, it is important for young people to pay attention to job opportunities after graduation when choosing their studies, something that has become more the case in recent years (figure 2).

However, making education more labour market-oriented also entails risks. After all, rapidly changing society and technology, and thus labour market requirements, require workers to be able to adapt flexibly. Too close a match between education and the current jobs on offer can cause mismatches later in the career, to the extent that the young person lacks skills (social competences, eagerness to learn, creativity, desire for continuous training...) that make such an adaptation smoothly possible. Therefore, in addition to job-specific knowledge and competences, a more general, broad-based basic education that focuses on such skills remains useful. It also remains important to let young people choose a course of study not only taking into account the chances of direct employment but also based on their interests, talents and intrinsic motivation, especially since these also largely determine the chances of success in education. Due to demographic conditions, vacancies are likely to occur in most sectors and occupational groups in the coming years. This will facilitate young people’s choice of training or studies that they like.