Labour hoarding is making the US labour market very tight

The recent labour market report showed that the US labour market is still running hot. Nonfarm payrolls increased by 517k in January, bringing the unemployment down to 3.4%. Meanwhile job openings kept growing, bringing the number of job openings to unemployed close to 2. The scarcity in the labour market is pushing firms to hoard labour in order to avoid labour shortages. Very low layoff rates, reduced average weekly hours and declining productivity all point to exceptional levels of labour hoarding. This has serious consequences, as it drives up wages and supports inflation, while keeping the labour market highly resilient to monetary tightening. It might make the recession less deep than expected, however.

Hoarding critical resources is a key survival strategy. To prepare for winter season, yellow pine chipmunks are known to bury food in different caches, while moles effectively paralyze and imprison earthworms for later consumption. To ensure survival this economic cycle, another wildly successful species, the US company, seems to be hoarding its critical resource, namely human labour.

Data points to unseen levels of labour hoarding

Evidence of exceptional levels of labour hoarding is piling up. When firms hoard labour, they are reluctant to lay-off even the less productive employees. Today, despite an ongoing economic slowdown and rising costs, firms are unusually reluctant to lay off workforce. Monthly layoff and discharge rates are at 1% of total employment, a 29% drop from pre-pandemic averages. As firms are hoarding labour, employees also have less to do. Average weekly hours worked, which increased to 34.7 last month are still down 0.3 hours since January 2021. Even more noteworthy, despite all the talk of the pandemic accelerating technologic change, labour productivity has surprisingly declined by 1.5% last year (see figure 1).

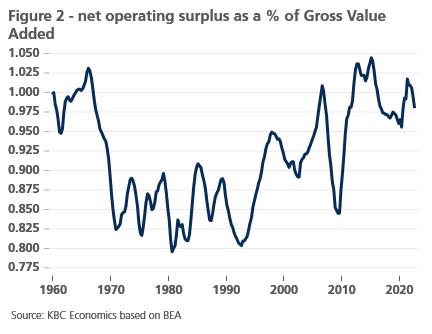

The current drive to hoarding labour is caused by multiple factors. First, the labour market is still exceptionally tight as the rate of vacancies to unemployed remains close to 2. In such circumstances, it is more difficult for firms to replace unexpected departures (see our opinion on labour hoarding in the Belgian economy). Having excess labour at your disposal then comes in handy. Second, corporate profitability remains elevated, allowing firms to absorb the higher labour costs (see figure 2). As usual, Covid worsened the problem. As Covid increased temporary absences, excess labour allowed firms to avoid operational disruptions.

Labour hoarding has surprising economic consequences

Excessive labour hoarding creates problems. It causes further tightness in the labour market, driving up wages, which are up 5.1% y-o-y. It also makes the labour market more resistant to monetary tightening. Though the Fed hiked the Fed Funds rate by 4.25 pp in 2022, the unemployment rate remains at 3.4%, a 21st century low. While this low unemployment is generally a good thing, in the context of the Fed trying to cool inflation, it is a complicating factor.

Nonetheless, when the Fed eventually breaks the back of the labour market, a relatively rapid rise in the unemployment rate can be expected. Once the labour market loosens slightly, a snowball effect could start. Some firms, especially those facing margin pressure, could fear temporary labour shortages less, as replacements will be easier to find, and will thus shed their excess labour. The resulting increase in unemployment could convince even more firms to shed their excess labour. A high unemployment rate would be the final result.

The ensuing higher unemployment rate will not necessarily translate into a deep recession, however. As firms will likely compensate their loss in labour units by increasing working hours and labour productivity, economic growth will likely slow down, but not turn (deeply) negative over the year 2023. That’s one reason why we expect economic growth to remain at a year-average of 1.2% in 2023, despite the ongoing severe monetary tightening. Adaptation is key to survival, both in nature and in the economy. In 2023, as the economic winds shift, US companies will again showcase their extraordinary adaptive capabilities.