International trade can save or break the recovery

The corona crisis is hitting our economy hard. Nevertheless, the next challenges are already underway. The US-China trade war has returned and is only a harbinger of a new wave of protectionism that will plague the global economy. Rising trade tensions are not unrelated to the corona crisis. After all, the corona crisis has disrupted international production chains and is causing companies to shift their focus to the domestic market. Governments, in a defensive mode, are supporting such a business strategy to stimulate the domestic economy. The flare-up in the US-Chinese trade conflict, and its extension to Hong Kong, is a matter of great concern as it sets the tone for the post-crisis period. As trade can generate positive growth dynamics, the speed and sustainability of the economic recovery will depend on the extent to which this protectionism gives way to free world trade.

Same old story

International trade can be very volatile. Traditionally, world exports grow faster than the world economy, which has led to an increase in the openness of the world economy, measured as the ratio of world exports to world GDP, in recent decades. We call this phenomenon globalisation (see KBC Economic Research Report of 30 April 2020). But in periods of crisis, international trade also falls far more sharply than general economic activity. The fall in demand during a crisis period leads to lower import demand. Moreover, international activities are always riskier, which puts pressure on the financing of export activities, for example, or delays major international investments. An economic shock also typically causes a chain reaction that puts pressure on international trade worldwide. That is no different this time. The corona crisis is leading to a sharp drop in international trade, as shown by the first monthly statistics.

Nevertheless, the corona crisis is different from previous crises in terms of trade, mainly because a number of effects are of a lasting nature. In the initial phase of the virus outbreak, the closure of Chinese companies and disruptions in supply lines from China already disrupted international trade. Some final products became scarce abroad, but even more important was the disrupted supply of intermediate products which also caused problems for Western companies. This supply shock came unexpectedly and made many Western multinationals realise that they are vulnerable to such international events. Some policymakers take advantage of this fear to encourage companies to move production back to their home market, or at least to become less dependent on their foreign supply routes. This exacerbates the downward pressure on international trade that was already visible earlier, in particular through the more assertive attitude of the US government towards trading partners. On the eve of the corona crisis, optimism grew that the US and China would bury the hatchet, but even the Phase 1 trade agreement of January 2020 offers little guarantee of a definitive end to trade hostilities.

US and China at it again

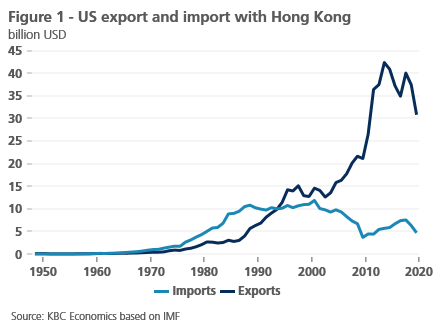

In the meantime, the US and China are once again facing each other with knives pulled. The accusing American finger, pointed towards China as responsible for the Covid-19 pandemic, puts the relationship back on edge. China’s tougher stance on rebellious Hong Kong adds an extra scoop to the tense relationship. Once again, international trade is the instrument with which the political confrontation is settled. Moreover, the US no longer wants to recognise Hong Kong as a region that can operate autonomously from China. Not only does this jeopardise Hong Kong’s position as an international financial centre, but it may also lead to less favourable treatment of Hong Kong’s exports to the US. Ultimately, the US could extend trade barriers imposed on China to Hong Kong. However, this seems to be a bridge too far as the US has a significant trade surplus with Hong Kong (figure 1). Far-reaching trade sanctions against Hong Kong could return like a boomerang and hit US exporters. On the other hand, if the US continues with its threat, this shows once again that the so-called trade war is not about trade, but about economic and political influence. Trade is only abused for that purpose.

Thus, the corona crisis threatens to quickly turn into a new international conflict that will once again damage the world economy. This puts the economic recovery after the corona crisis at particular risk, but also threatens damage in the longer term. Strong export growth would support global recovery. It is not the direct effect of exports on economic growth that is important, because increasing exports often go hand in hand with increasing imports. As a result, the direct contribution of net exports to growth remains limited. But new export opportunities create positive and indirect growth dynamics. Better export prospects lead to more investments by companies. Access to foreign products, services, and especially technology help the domestic economy. These dynamic effects support the recovery in the short term, but above all increase potential growth in the longer term.

Fears that the post-corona era will be structurally more protectionist are justified. The current trade tensions between the US and China are exacerbating these fears. It is even understandable that in periods of economic crisis countries are more defensive towards foreign companies and try to support their own companies. But history shows that it is best to abandon this protectionist attitude in order to speed up economic recovery. The world succeeded in this in 2009 after the financial crisis. Today this seems much more difficult.

Fortunately, Europe continues to take the lead in stimulating international trade. As a trading block, we do this out of self-interest, but the current efforts will probably be insufficient. In the recently announced European Recovery Plan, it is striking that the focus is almost exclusively on the domestic European economy. The plan rightly emphasises the importance of investment and structural reforms in the EU member states and provides a budget for this, although the resources are undoubtedly just a drop in the ocean. Unfortunately, the European Recovery Plan does not take into account the deteriorating international context for European exporters. The EU apparently believes that after the corona crisis, international markets will return to business as usual. Therefore, according to the European Commission, the current EU external trade policy offers sufficient guarantees to defend European international interests. This attitude is too optimistic and naive. It is time to adapt to the new reality.