Housing market acrophobia in some EU countries

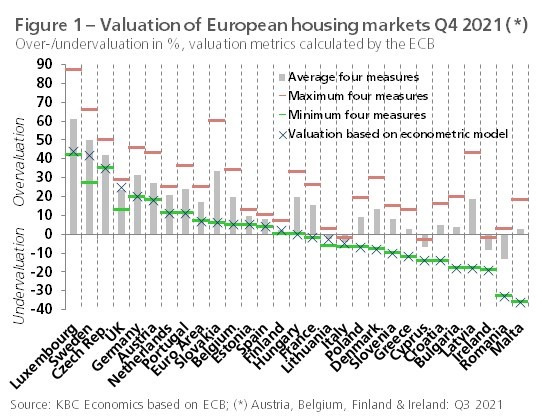

The European Central Bank (ECB) has recently published an update of its valuation measures for housing markets in the European Union countries (although no longer in the EU, the UK is also included). The latest figure refers to the fourth quarter of 2021, with the exception of Austria, Belgium, Finland and Ireland, where the latest figure refers to the third quarter. The ECB calculates four measures of over- or undervaluation, based respectively on: (1) the price-to-income ratio, (2) the price-to-rent ratio, (3) a bond-yield-to-rental-earnings ratio, and (4) an econometric model. The model-based calculation is often considered the most reliable. The econometric model approach estimates an equilibrium price on the basis of fundamental determinants (income or GDP per capita, interest rates, housing stock, etc.). When the actual recorded house price deviates from this equilibrium price, the model indicates an under- or overvaluation.

Figure 1 ranks the EU countries (including the UK) according to the situation of their housing market, from most overvalued to most undervalued, as reflected in the model approach (average, minimum and maximum of the four measures are also shown for information). Especially in Luxembourg (+44%), Sweden (+42%) and the Czech Republic (+35%), the ECB model (but also the other approaches) points to a substantial overvaluation at the end of 2021. Furthermore, the model estimate of overvaluation is also quite high in the UK (25%), Germany (20%) and Austria (18%). For Belgium, the ECB's model estimate of +5% is notably lower than what other institutions, including the NBB and KBC Economics, put forward as overvaluation (and also lower than the Eurozone figure of +7%). At the other end of the spectrum we find Romania (-33%) and Malta (-36%) where, at least according to the ECB model, the housing market is significantly undervalued.

More expensive markets

Figure 2 shows the evolution of the over- or undervaluation, based on the ECB model, during the two years of the pandemic. At the end of 2021, 21 out of 28 countries had an over- or undervaluation figure higher than at the end of 2019. In 6 countries (the Czech Republic, the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and Slovakia) it was even 10 percentage points or more higher. In most housing markets, despite the heavy impact of covid-19 on the economy, prices continued to rise strongly over the past two years. The fact that markets remained buoyant in difficult economic conditions was due to low interest rates and the income support that affected citizens received during the pandemic. This supported the affordability of real estate. The combination of low interest rates and an uncertain economic climate also stimulated investors' interest in real estate. In addition to continued strong demand, the price boom of the past two years in many countries was also due to the slow adjustment of the housing supply.

The sharp rise in overvaluation and its high level in some countries (mentioned above) raises the question of whether the market is overheating. The fear of a 'bubble' is justified, but it is difficult to predict whether, and if so when, this will lead to a price correction in the countries concerned. In any case, we expect price dynamics to weaken this year and next in most EU countries, but to remain positive. Given the currently very high inflation, house prices in real terms (i.e. adjusted for general price increases) are likely to decline. The expected cooling follows the ongoing rise in interest rates as well as the less favourable economic climate and increasing uncertainty due to the war in Ukraine. However, there is a chance that nominal house prices will continue to rise more strongly than expected, driven for instance by sustained investor interest. If so, for some countries this implies the risk of a (sharp) market correction sometime in the future.