The Fed should return to forward-looking inflation targeting after next policy review

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.960.9999.jpeg.cdn.res/last-modified/1732797909865/cq5dam.web.960.9999.jpeg)

In its policy review of 2020, the Fed adopted an average inflation targeting strategy. However, there are conceptual problems with this strategy, the main one being that past inflation should not matter for a forward-looking policy maker. Moreover, other major central banks have either not followed the Fed’s example (the case of the ECB), or returned from (implicit) average inflation targeting to forward-looking inflation targeting again (the case of the Bank of Japan). Therefore, the Fed should return to traditional forward-looking inflation targeting after its next policy review, expected for 2025.

In August 2020, the Fed concluded its latest monetary policy review. These reviews are intended to be conducted approximately every five years, which means that the next one will probably take place in 2025. The Fed’s 2020 review was consequential. One of the main outcomes was the shift from traditional (forward-looking) inflation targeting to average inflation targeting.

A new strategy in 2020

One of the main motivations for this change appears to have been to help anchor inflation expectations close to the Fed’s inflation target of 2% after a prolonged multi-year period of below-target inflation. However, average inflation targeting, as officially implemented by the Fed since August 2020, is conceptually not necessarily a good idea (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 9 October 2020). It has flaws since it is similar to implicit price level targeting. While there is a theoretical case for targeting a moderately positive inflation rate in a world with nominal price rigidities (facilitating changes of relative prices and thus supporting the efficient allocation of resources), the case for directly targeting the price level appears less convincing. The main reason is the backward-looking nature of an average inflation target, as opposed to the forward-looking nature of a traditional inflation target. If the argument in favour of a moderate inflation rate is that it ‘greases’ the functioning of the economy, past inflation rates should not matter.

The ‘make-up’ feature of average inflation targeting sooner or later leads to a monetary policy dilemma. If too low inflation is caused by economic slack, it is not controversial that the central bank allows this slack to be fully eliminated before tightening, even if that comes at the cost of temporarily higher inflation. On the other hand, the central bank will probably not follow the same reasoning if temporarily higher inflation occurs in combination with strong growth and low unemployment. When such a temporary positive demand shock is fading out, it is not credible that the central bank will deliberately slow down growth and raise unemployment only to reach its backward-looking average inflation target. In other words, an average inflation targeting plan is not fully time-consistent in the sense that the central bank cannot credibly promise today to pursue this objective in the future because its incentives will have changed by then.

In its 2020 policy review, the Fed apparently intended to mitigate this time-inconsistency problem by introducing an asymmetry in the announced inflation compensation rule.Strictly speaking, the strategy only refers to a future upward inflation compensation after a period of below-target inflation Conceptually, this asymmetry indeed addresses the mentioned lack of credibility after a period of above-target inflation, as is currently the case. This asymmetry suggests that recent periods of above-target inflation are not taken into account when the Fed considers its desired near-term inflation path. The question of how exactly these exclusions of past (high) inflation rates feed through into the Fed’s reaction function, further complicates the proper formation of stable market inflation expectations. The need to make these kinds of implicit calculations (including the risk of assuming wrong parameters of the Fed’s objective function) enormously complicates matters for markets and could lead to volatile and unanchored inflation expectations. These, in turn, would likely to lead to a higher inflation risk premium required by bond markets.

Outlier

Besides the fundamental arguments against average inflation targeting, there is also the observation that no other major central bank uses this strategy at the moment. In its 2021 monetary policy strategy review, the ECB did not follow the Fed’s example and stuck to traditional inflation targeting. The ECB did change the target from ‘below, but close to’ to a symmetrical target of 2% but kept its forward-looking nature. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) abandoned its ‘make-up’ strategy to return to traditional inflation targeting after its 2024 monetary policy strategy review. The BoJ abandoned its ‘inflation overshooting’ commitment, which was implicit average inflation targeting. In the Japanese case too, this previous commitment was linked to the intention of affecting inflation expectations (in Japan this meant raising them to the inflation target of 2%). However, after the recent inflation uptick in Japan, the BoJ considers this to be achieved and therefore returned to traditional forward-looking inflation targeting.

Already abandoned in practice

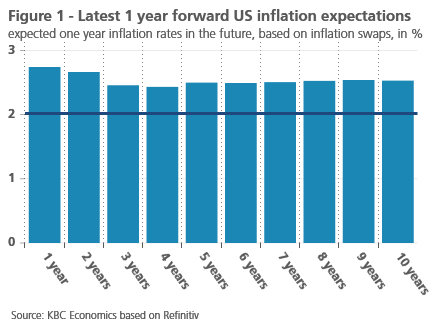

Despite the lack of transparency of the average inflation targeting rule, market inflation expectations for the US have nevertheless remained broadly anchored and, after the energy price shock of 2022, have gradually moved back towards the longer run inflation objective (Figure 1). The reason could be that markets may just have ignored the average inflation strategy altogether because of its complexity. A second plausible hypothesis is that markets implicitly believe that the Fed itself abandoned the strategy. Indeed, the Fed does not refer in any way to average inflation targeting in its policy communications anymore. As a result, for all practical purpose, the Fed is behaving like a classical inflation targetter. For example, in the statement after the latest policy meeting of 7 November 2024, the Fed only referred to a forward-looking inflation target: “The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run.”

The most plausible reason for this tacit abandonment by the Fed is that the 2020 policy strategy was designed to come out of a period of low inflation and that the Fed would not have chosen this strategy in the first place if it had known that an unprecedented upward inflation shock was imminent.

For these reasons, the Fed should not hesitate to explicitly change the strategy back at the occasion of the next review, which will probably be held in 2025, to the previous forward-looking inflation targeting of 2%. After all, the Fed updated its strategy in the past as well when needed. Until 2012, the Fed did not even have an operational definition of ‘price stability’. It was not until 2012 that the Fed defined this as an ‘inflation rate of 2%’. Similarly to the strategy change in 2020, at least part of the intention was to anchor markets’ inflation expectations, since it was in the same year as the announcement of the third round Quantitative Easing (QE3). The open-ended nature of this programme (nick-named “QE infinity”) might otherwise well have cast doubts in the markets’ eyes on the Fed’s commitment to price stability in the longer run.

Protecting the Fed’s independence

Preserving the credibility of the Fed’s commitment to the pursuit of price stability, is all the more important in a political context that seeks to undermine the Fed’s independence. US president-elect Trump will almost certainly exert pressure on the Fed to bring interest rates down to levels below the level that the Fed would otherwise consider to be appropriate to deliver its inflation target. Explicitly changing the Fed’s dual policy mandate may face too high a political hurdle in Congress for Mr Trump, but appointing a more lenient Chair as a successor to current Fed Chair Mr Powell in 2026 is very likely. Keeping in mind the importance of central bank independence and credibility for delivering on price stability, it is all the more important to strengthen the Fed’s policy framework, making monetary policy less dependent on politically motivated views of individual Fed FOMC members (including the Chair). Explicitly returning to a transparent forward-looking inflation targeting strategy would be part of that effort.

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.480.9999.jpeg.cdn.res/last-modified/1732797909865/cq5dam.web.480.9999.jpeg)