Green competition and opportunities are coming

.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.960.9999.jpeg.cdn.res/last-modified/1672930161835/cq5dam.web.960.9999.jpeg)

The EU Green Deal makes clear that the EU wants to be the global leader in terms of climate initiatives and green technology. The decision to commit 30% of the post-Covid recovery fund to the EU’s climate protection and emission reduction goals, and the decision to issue green bonds to finance the recovery, will help solidify this role. But other world powers are also stepping up their climate ambitions, with both China and Japan committing to carbon neutrality by 2060 and 2050, respectively. The US is also likely to take a more serious approach to the climate crisis with the recent election of Joe Biden as the country’s next president (though more aggressive policies will likely be thwarted if Republicans keep power in the US senate). These commitments from major world powers are undoubtedly welcome news for the fight against climate change, but they also suggest that it will be no easy task for the EU to maintain its position as a green leader. To remain competitive and take advantage of the new global opportunities that will present themselves in the march toward a greener economy, both the EU and its member states should steer clear of greenwashing their recovery plans or watering down new Green Deal regulations

Green leaders

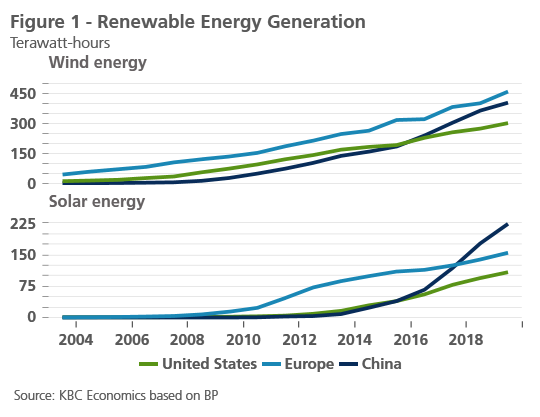

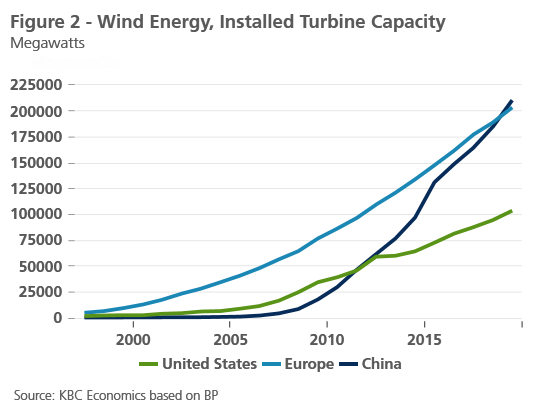

Many would argue that Europe is already the global leader in the fight against climate change. The emissions trading system launched in 2005 is the world’s largest carbon market, for example, and the European Green Deal has the ambitious aim of revamping the EU’s economic system and achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. The EU also leads in terms of renewable energy advances, particularly with regards to wind energy. However, as figures 1 and 2 make clear, China is quickly catching up, and has surpassed Europe in terms of both solar energy generated and wind turbine capacity installed. Furthermore, the EU is not the only major power with a commitment to achieving a carbon neutral economy in the next 30-40 years. Following the signing of international climate treaties such as the Paris Agreement, Japan, South Korea, and China all announced such commitments over the past three months. Meanwhile, the US has been the clear climate laggard in recent years, with the Trump administration pulling the US out of the Paris Agreement. However, US president-elect Joe Biden has committed to rejoining the Paris Agreement when he takes office in January and ran his campaign on a platform that included reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. The extent to which the US will actually implement an ambitious climate agenda depends on whether Republicans or Democrats take control of the Senate in January. But despite this uncertainty, the trend toward clean energy and a more sustainable global economy are clear.

But what benefit comes from being the leader in green technology? Aside from the environmental advantages, much of it boils down to keeping a competitive edge as the global economy undergoes a significant transition. The transition to a more sustainable economy isn’t just about isolated advancements in renewable energy. Rather the idea is that cheaper, more abundant, and cleaner energy will eventually be integrated throughout the economy, including industrial activities1. An example of this would be the use of wind generated electricity to produce hydrogen, which would then be used to power industrial activities with a lower emissions footprint. A recent report by the International Energy Agency suggests that renewables will overtake coal as the largest source of electricity generation worldwide in 2025, and that in Europe, the UK and the US, increases in renewables will outpace demand, which on the whole suggest declining prices2. Hence when we consider carbon pricing (which is likely to increase under the green deal), carbon border taxes (which may become more prevalent as more countries adopt targets to become carbon neutral), and general advancements in technology, green processes can be expected to become cheaper and gain a competitive advantage over polluting processes in the not so distant future. What’s more, new products, services and technologies that support the greening of the economy can also be exported elsewhere. Hence, those that lead in the climate transition will have a competitive advantage over those that lag behind.

Another advantage, particularly for Europe, in promoting renewable energy capacity is that this reduces dependence on imports of fossil fuels. As a recent European Commission report on clean energy competitiveness points out, the risk of becoming more dependent on raw material imports is countered by the fact that raw materials can remain and be reused in a circular economy4. This same report, however, suggests that the EU currently has the lowest research and innovation (R&I) investment rate in clean technologies as a percent of GDP compared to other major economies. Furthermore, both private and public clean energy R&I are declining, which is clearly inconsistent with the goals of the Green Deal. Perhaps the combination of increased competition and political initiatives can turn this trend around.

An opportunity in the recovery

Indeed, realizing the type of wide-scale economic transformation envisioned in the Green Deal requires significant investment. The recovery initiatives undertaken as a result of the Covid-19 crisis are an opportunity to increase investments in green technology. And so far, European economies are committing a greater portion of their recovery plans to sustainable efforts compared to other nations (a private research group, Rhodium, estimates that taken together, 20% of EU stimulus and member states’ stimulus will focus on green spending compared to 1-3% for the US, China and India. Amounts differ between member states with France committing one-third of its stimulus to green initiatives and Germany committing 11% of its stimulus). However, some question whether the EU recovery fund will be ‘green enough’, even with the Next Generation EU’s ‘do no harm’ principle and a commitment that 30% of funds will go to green projects. Implementation is left up to the member states, and the criteria by which the Commission will judge member states’ plans is not fully clear. Furthermore, critics say that the ‘do no harm’ principal is not sufficiently binding, and funds could still be used to support high polluting activities.

This does not necessarily mean that policymakers in member states will skirt green conditionality or commit only the bare minimum of recovery funds to green activities, and indeed, doing so would not be wise. Green competition is on the rise and presents an opportunity for countries that invest in green technology and in achieving a more sustainable economy. The EU has an opportunity to remain a global green technology leader. It is an opportunity that shouldn’t be squandered, both for the good of the environment and for the good of the economy.

1. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_20_12952.

2.https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2020/renewable-electricity-2#forecast-summary

3.https://eurlex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/uri=CELEX:52020DC0953&from=EN

4. https://eurlex.europa.eu/legalcontent/EN/TXT/PDF/uri=CELEX:52020DC0953&from=EN

https://rhg.com/research/green-stimulus-spending