Getting rid of vacant commercial premises in Belgium

If you stroll through the shopping streets, you cannot deny it: many commercial premises are empty. In recent years, the vacancy rate in Belgium has risen sharply to almost 12% by the beginning of 2021. The increased importance of online shopping is an important cause, but certainly not the only one. The development is worrying and requires a multitude of resolute and creative solutions. In addition to making city centres more attractive and stimulating new entrepreneurship in commercial centres, efforts must also be made to eliminate the oversupply on the Belgian retail market. The fact that relatively fewer commercial properties were reallocated helps to explain why vacancy levels in Belgium are significantly higher than in the neighbouring Netherlands.

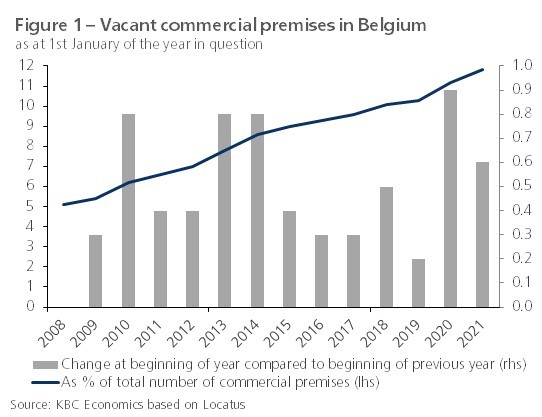

One of the most disruptive elements for a lively and attractive streetscape is the vacancy of commercial premises. According to retail data collector Locatus, the vacancy rate in Belgium has more than doubled in recent years, from 5.1% in early 2008 to 11.8% in early 2021 (see Figure 1). The increasing vacancy rate (around 24,000 premises at the beginning of 2021) occurred despite a decrease in the total number of commercial premises during the period. This mainly concerns smaller retail businesses (mostly in the fashion sector) in smaller central municipalities, but there are also many vacant premises in larger shopping cities. In Flanders, vacancy rates are highest in Limburg (13.3%) and lowest in West Flanders (10.1%). In Wallonia, Hainaut (16.1%) and Walloon Brabant (10.2%) have the highest vacancy rates. In Brussels, the vacancy rate is 11.2%

Causes of vacancy

The increasing vacancy rate has several causes. In the first place, it is related to trends that have been going on for some time, and which are related to changed purchasing behaviour and new shop concepts. The best known are the fast-growing popularity of online shopping and the advance of shopping centres and retail outlets outside city centres. People are also spending less and less of their budget on fashion and expensive goods (and more on trips, journeys, festivals, etc.), which is reflected in the rise of cheap chains such as Primark and Action. In addition, an increase in scale in the retail sector also plays a role, with the often older buildings in the centre no longer meeting the contemporary requirements of businesses. Furthermore, vacancy often has a catalysing effect, whereby a long-term unoccupied building can cause more vacancy in the neighbourhood, certainly when this is accompanied by neglect (the broken window syndrome). In this way, an entire neighbourhood can enter a downward spiral. The reduced attractiveness reduces the number of passers-by, which is particularly detrimental to shops that live on impulse purchases.

Finally, the increased vacancy rate is also related to the successive economic crises that have occurred since 2008 (the Great Recession, the Sovereign Debt Crisis and the Covid Crisis). It is worth noting that the strongest increase occurred between the beginning of 2019 and the beginning of 2020. During the Covid year of 2020, when all restaurants and non-essential shops had to close twice for long periods of time, the increase in vacancy levels was still limited overall (see figure 1). The fact that the effect of the pandemic on vacancy levels was relatively modest is surprising given the increased importance of e-commerce during the crisis (see figure 2). Likely, the massive government support was able to dampen the increase in vacancy levels. At the beginning of this year, Locatus still expected that, as the support measures were phased out, many retailers would not survive this and that the vacancy rate would therefore increase further to a predicted 13.3% at the beginning of 2022. In the meantime, the Belgian economy is recovering faster and more strongly than previously thought, mainly thanks to the rebound in household consumption, so this figure is probably too negative.

Tackling of vacancy

A certain amount of vacancy is not a bad thing in itself, on the contrary. Frictional vacancy (estimated at around 2%) is necessary because it provides the supply that enables movement and renewal in the retail market. Moreover, vacant space provides room for the redevelopment of neighbourhoods where there is a need for new functions (e.g., residential, cultural, sports, etc.). Vacancy only becomes a problem when it becomes structural and several buildings in a particular location are left without a long-term (re)use. The solution to the problem is not simple, however, and requires a variety of resolute and creative responses. Many cities and municipalities are already making efforts in many areas, with varying degrees of success.

First of all, it is important to create a sufficiently attractive environment in town and city centres, in which the interweaving of the functions of living, working, shopping and relaxing creates a favourable habitat for flourishing shopping streets. This includes the redevelopment and beautification of commercial cores and streets in such a way that the atmosphere and experience, as well as accessibility by various modes of transport, are improved. In addition, many specific supporting measures are needed, for example: fines for vacant properties, establishment bonuses, limiting peripheral large-scale retail locations and ribbon building, stimulating living above shops, good city marketing, responsibly relaxing urban development regulations, etc. All of this requires sound planning and a sustained policy over several years. If necessary, temporary solutions are needed (e.g. pop-up stores, stickering of empty premises, use by neighbouring shops or local artists, etc.) to avoid reaching the tipping point where the vacancy rate quickly spreads (according to American research, this is about 6%).

It is also necessary to stimulate new entrepreneurship in commercial centres. There is a shortage of newcomers in Belgium, especially young people, who show an interest in opening a business. The lack of initiative is partly due to the generally weak entrepreneurial culture in our country, with relatively few start-ups compared to many other European countries. Incidentally, (new) retailers must also pay sufficient attention to innovative concepts and earning models (e.g. experience shops) in order to minimise the risk of failure (and consequently vacancy). Related to this is also an eye for sufficient profitability and professional management.

Finally, care must be taken not to create an oversupply of new shops. In Belgium, too many new shops are sometimes added in scattered locations, which are, on balance, unnecessary and therefore have little chance of success. In the neighbouring Netherlands, relatively more shop premises have disappeared or changed their function in recent years, as a result of which the vacancy rate is significantly lower there (7.5% at the start of 2021). Belgium currently has some 18 retail outlets per 1000 inhabitants, compared to only 13 in the Netherlands. This means that certain commercial premises might preferably disappear from the stock and be given a different use more quickly.