EU funding for Central and Eastern European regions remains essential

The EU financial framework post 2020 should continue to prioritize economic convergence. Despite progress in income convergence between EU member states, regional income differences remain huge. In particular in Central and Eastern Europe, catching-up with the average EU income level has been limited to capital and urban regions. More emphasis should be put on the regional dimension in future EU convergence policies. Moreover, it is still the new EU member states that are require most financial support. Rather than offering additional financial support to Southern European countries, the latter would benefit more from structural policy improvements.

Next week, the European Commission will use its initiation right to launch a first draft for the next Multi-annual Financial Framework (MFF) starting in 2021 for a 7-year period. The MFF is the EU’s budgetary planning tool which reflects political priorities in the longer term. Those priorities are then translated into future EU spending programmes. One of the political aims within the EU is real macroeconomic convergence - or an economic catch-up - among the EU member states as well as among regions within these member states. To achieve its goals, the EU channels financial support via different funds. The Cohesion Fund (CF) focuses on countries where the gross national income per inhabitant is less than 90% of the EU average. By funding primarily transport and environment projects the CF aims to reduce economic and social disparities and helps lagging countries in their economic development. Meanwhile, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) tries to strengthen economic cohesion in the EU by correcting imbalances between the regions.

Convergence achievements

The comparison of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per inhabitant to the EU average is generally used as a measure of economic convergence. Substantial income differences across the EU point to the desirability of income convergence policies. Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia - the newest EU Member States - are the convergence laggards within the EU. Their living standard is still less than 60% of the EU’s average. More remarkably, Greece - a longstanding EU member since 1981 – is also in the bottom five. Greece undoubtedly experienced a catching-up effect, even during the period before actual EU membership. However, after the financial crisis the Greek economy fell back compared to its European peers. By contrast, Luxembourg and Ireland are the largest positive outliers. Their GDP is, however, artificially boosted by the presence of multinational firms and hence biased on the upside. Disregarding this, the Netherlands, Austria and Denmark are at the top of the comparison. Nevertheless, despite continued differences, a significant amount of progress has already been achieved. The Central and Eastern European countries as well as the Baltics, especially, have managed to substantially increase their standard of living relative to the EU average. Various studies have assessed the impact of EU funds on economic convergence. Though there is some debate on the impact of EU financial support, and even more on the effectiveness, most studies acknowledge the overall positive contribution to national and regional economic development.

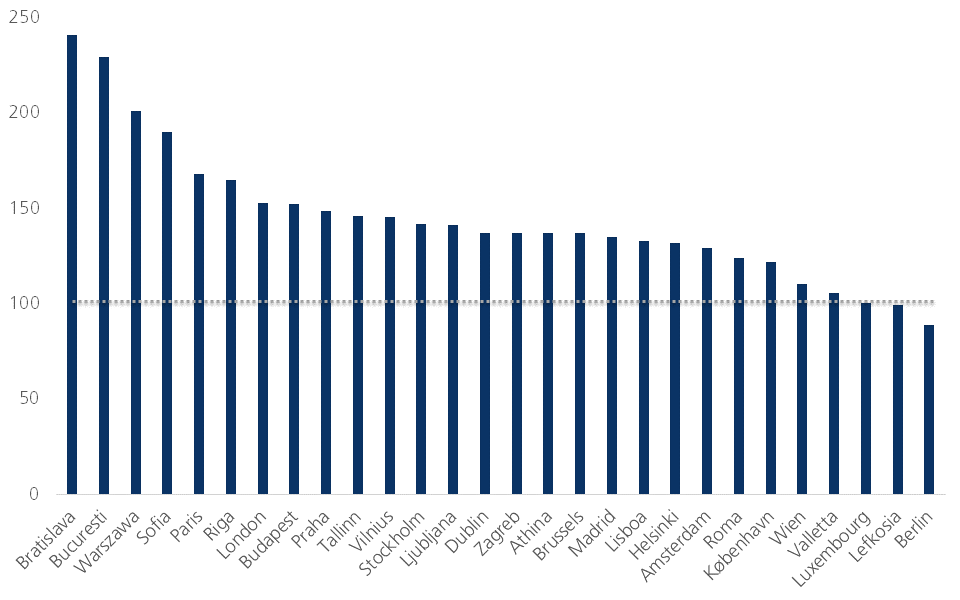

However, the job hasn’t been finished yet. As the centroid of the EU economy is located in a well-known banana-shaped zone in Western Europe – ranging from Manchester (UK) to Milan (Italy) with some extensions in the Nordic region – economic activity remains geographically concentrated. Countries outside this core region are at best peripheral suppliers to the core. Consequently, convergence at the country level is incomplete. More strikingly, regional dissimilarities within countries also remain huge. Contrary to a clear convergence trend on the national level in Central and Eastern European countries, large regional income disparities in the same area are evident. There is a particular contrast between the capital regions and the other regions. It seems capital cities have been the main beneficiaries from EU funds supporting economic convergence, while the rest of the country lags behind. Though urban areas, and mainly capital cities, in most countries are characterized by higher incomes, the discrepancy in the eastern part of the EU is striking (figure 1). This situation should be improved, not only out of fairness, but also to reduce congestion issues (mobility, housing etc.) in the capital cities and to boost country-wide welfare levels.

Figure 1 - GDP per capita for capital city regions (national average = 100; based on PPS per inhabitant, 2016)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Eurostat (2017)

Revising EU policies

Hence, although the country aggregates show a relatively benign image of convergence, regional details still point to large living standard differences between regions, for both new and old EU Member States. Therefore, to ensure a higher inclusiveness of economic progress, European convergence policies should aim to diminish interregional rather than international differences. Although already more European financial support flows via the ERDF – which has a more regional focus - than via the CF, the new Financial Framework for 2021-2027 could be an opportunity to allocate European funds in a way that would tackle the large interregional disparities even better.

In the ongoing debate some have argued that the EU should reorient its financial support away from Central and Eastern Europe towards Southern Europe. There are mainly political arguments behind this idea, namely a financial punishment for countries with an EU-critical stance. Nevertheless, at first glance, this approach would make sense from an economic perspective too. As Southern Europe suffered substantially during the financial crisis and its aftermath, more financial support would be welcome in the region. However, this approach would not be wise. First, as argued above, the regional disparities in Central and Eastern Europe are still substantial. Second, rather than financial support, Southern Europe needs structural reforms. Some EU funding will be helpful, if used effectively and efficiently, but too much EU funding would reduce the urgency of reforms. That could only lead to a worse economic outcome.