Energy crisis hides more persistent problems in supply chains

The normalisation of delivery times, production backlogs and container rates suggests that the worst of the problems in global supply chains is behind us. The reopening of China's economy and the accompanying wave of infections and absenteeism may bring another temporary increase in Chinese delivery times, but these economic costs do not outweigh, in terms of supply problems, the benefits from avoiding new lockdowns and port closures as a result of a persistently enforced zero-COVID policy. What does this perceived turnaround mean for inflation and economic growth in the euro area? To give a solid answer to this, we need to dig deeper and look at the underlying economic shocks behind the normalisation of supply chains.

Chinese reopening

China changed its COVID policy during the fourth quarter of last year, leading to a strong increase in the number of COVID cases. Given the relatively low vaccination rate among the Chinese population with less effective vaccines and a lack of natural immunity that previous exposure to the virus would have generated, this wave of infection is accompanied by a rise in absenteeism. In the short term, this is causing - besides a lot of human suffering - problems in the economy and supply chains, which can be seen, for example, in the delivery times of Chinese companies. PMI figures relating to these delivery times dipped last month (equivalent to an increase in delivery times). A lack of effective and/or broad vaccination also increases the risk of similar problems in the future with new waves of infections (by new variants). Labour shortages are obviously less problematic than a complete lockdown and closure of a port, for example. Despite the many challenges facing the Chinese economy (read more: Debt, decoupling, and diversifying growth: China’s many challenges), in the short term the excess demand resulting from the reopening of the economy will also lead to longer delivery times.

Different types of supply shocks

How does the reopening of the Chinese economy translate into European economic figures? For the third quarter of last year, we measure in our model a strong positive supply shock, which we associate with the removal of barriers in global supply chains. In the fourth quarter, however, partly due to the Chinese issues described earlier, we do not measure an additional positive bottleneck supply shock anymore. For the third and fourth quarters of last year, we estimate the impact on euro area GDP growth of the reduction of supply barriers (i.e., the positive supply shock) in the third quarter at 0.21 and 0.27 percentage points, respectively.

However, the measured positive bottleneck supply shock from the third quarter is insufficient to fully explain the fall in delivery times, production backlogs and container rates. Nor does the disappearance of supply chain overload (due to excess demand), which can be seen as an additional cause of high inflation and supply problems, provide a complete explanation. While no additional excess demand is observed, we do not see any convincing signs of sharply falling demand either (i.e., no observed negative demand shocks).

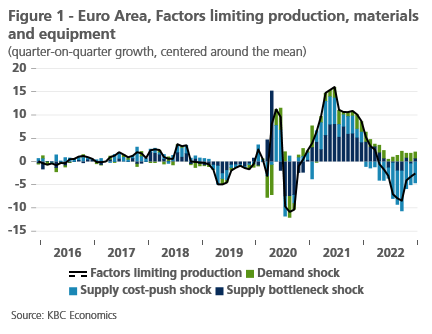

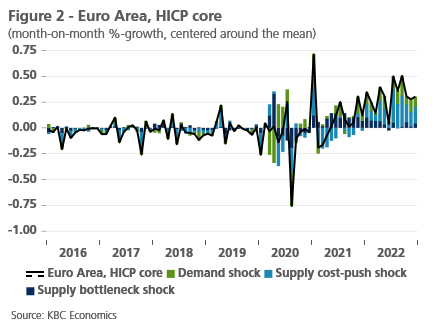

Much of the decline in delivery times, production backlogs and container rates can therefore be attributed to other supply shocks. In Figures 1a and 1b, we decompose an index showing how the shortage of materials and machinery limits output in the euro area, on the one hand, and core inflation, on the other, into three components. Using a SVAR model, we identify three economic shocks. First, a demand shock, which increases economic activity and core inflation and also puts pressure on the availability of materials. Second, a bottleneck supply shock, which decreases economic activity, increases core inflation and output constraints. Finally, a more general cost-push supply shock, which merely raises prices and reduces economic activity. After all, as economic activity declines, delivery times and production backlogs may also decrease.

Figure 1 shows that the growth of supply constraints in 2021 and the first half of 2022 is mainly explained by the impact of bottleneck supply shocks (dark blue). However, the decline in the index of production constraints in the euro area in the second half of 2022 is only partly attributed to positive bottleneck supply shocks. The bulk of this decline is due to negative supply shocks (light blue), which can be partly/primarily attributed to the energy crisis.

Impact on inflation

Figure 2 consequently makes it clear that excessive optimism about the mitigating impact of the easing of supply constraints on inflation was partly misplaced. Indeed, in 2021 and the first half of 2022, we find that bottleneck shocks contributed to the strong rise of core inflation, but the normalisation of supply chains in the second half of 2022 was accompanied by rising inflation due to cost-push supply shocks. The contribution to the strong rise of core inflation of the positive demand shocks, excess demand following the reopening of the European economy, is shown in green.

So, are these observations good or bad news for euro area inflation rates? It depends on how one looks at it. On the one hand, the positive bottleneck supply shocks in the second half of last year seem to have only marginally affected core eurozone inflation. On the other hand, this could mean that there is more room for additional positive bottleneck supply shocks during 2023, resulting in further easing of supply problems, a rise in GDP and a deceleration in inflation. The timing of these shocks remains uncertain in the current geopolitical context (i.e., it is difficult to forecast additional shocks occurring in the future). Without further easing, supply constraints and production backlogs could increase again when economic activity picks up as a result of falling energy prices. Decreasing, but not completely resolved problems in global supply chains may then become evident again.