Economic Perspectives January 2019

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The global economy has started 2019 on a more tentative footing. Weaker sentiment indicators globally, and more jittery financial markets suggest waning confidence may put downward pressure on growth prospects.

- Disappointing recent data for the euro area, including declines in industrial production in Germany, France, Italy and Spain, suggest that Q4 2018 GDP growth was weaker than previously anticipated, and momentum going into 2019 will be sluggish. A deterioration in manufacturing sentiment and industrial production is consistent with a less favourable global trade environment. The outlook isn’t all negative, however. The Euro area economy is still expected to grow at potential, and tight labour markets will continue to support higher wages

- Despite a notable drop in manufacturing sentiment in the US, the growth outlook continues to be positive and the labour market remains very strong. However, realized and expected inflation have declined somewhat due to lower oil prices. Given the more subdued outlook for inflation, as well as a marked dovish shift in Fed speak of late, we have lowered our expected path of Fed policy for 2019 from four hikes to two.

- Less than ten weeks from the scheduled departure date, the nature of the UK’s future relationship with the EU and the time and manner in which this will change is entirely unclear. The crushing defeat Theresa May’s proposed deal with the EU suffered in the UK parliament did not produce any coherent alternative. Financial markets have concluded that a ‘soft’ and probably later Brexit is now more likely but the next month could be very volatile.

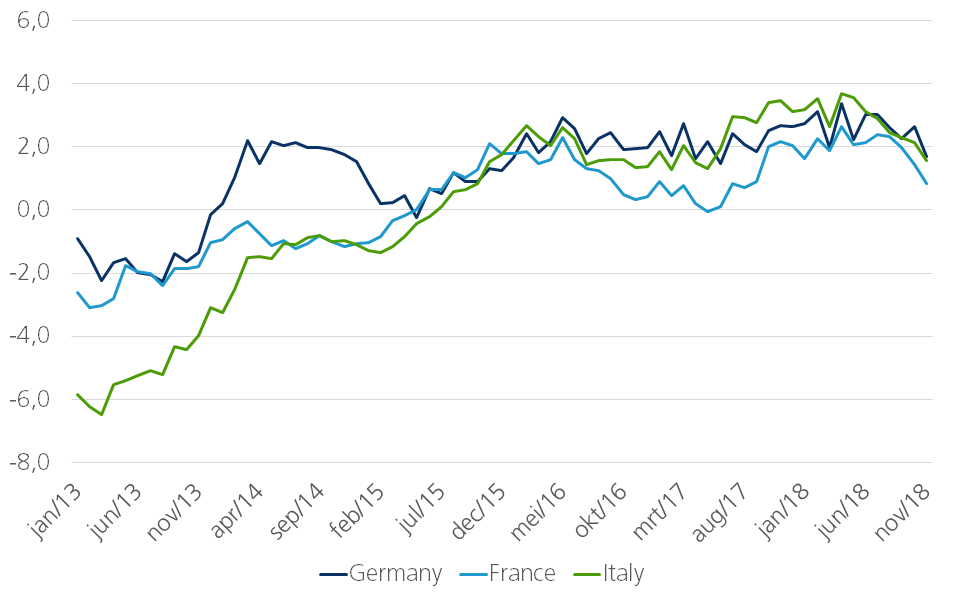

- Despite a still generally positive outlook for the global economy, uncertainty about economic conditions going forward has increased. As such, investors continue to seek safe haven assets and long-term benchmark yields have fallen. Together with slightly lower inflation expectations, it becomes difficult to see a likely trigger that results in higher benchmark yields. We have therefore revised down our expectation for both US and German 10-year government bonds for the end of 2019.

A cautious start to 2019

After a volatile end to 2018, the global economy is on more tentative footing at the start of 2019. Weaker sentiment indicators globally and more jittery financial markets suggest waning confidence may put downward pressure on future growth prospects. Hard data also suggests the manufacturing sector may be losing steam as uncertainty surrounding the global trade environment persists. Though recent volatility in oil markets has been driven, in part, by increased financial market volatility, the lower level and outlook for oil prices in recent months also reflect expectations for weaker global demand going forward.

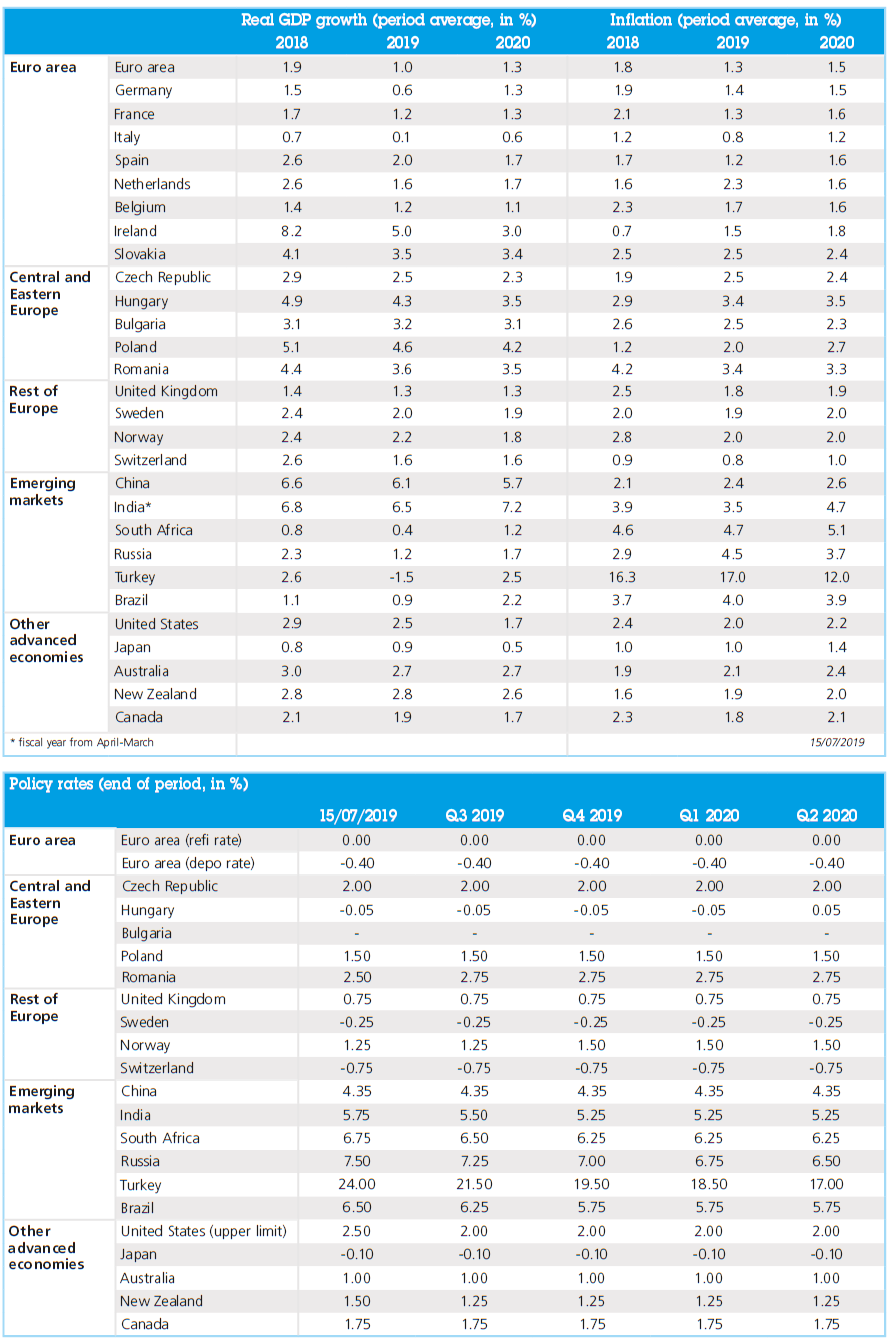

The outlook isn’t all doom and gloom, however. While PMIs have been shifting lower since the beginning of the year, they still point to expansion in most countries. Although global GDP growth is expected to decelerate through 2020, in most major economies growth remains above or close to potential with low unemployment rates and tight labour markets, which should give a boost to wages. Given several headwinds to growth, however, increased caution is warranted.

Figure 1: World PMIs

Hopes for an early Eurozone rebound are fading

A string of disappointing data releases for the euro area suggests that Q4 2018 GDP growth was weaker than previously anticipated and momentum going into 2019 will be sluggish. Eurozone business sentiment continues to slide with the manufacturing PMI declining for its sixth straight month in December. Though the decline in the services PMI has been less severe, it too has been on a downward trend for five months straight. That said, both manufacturing and service surveys remain consistent with positive growth for most, but not all, countries. In particular, French and Italian sentiment indicators suggest no forward momentum in these economies of late.

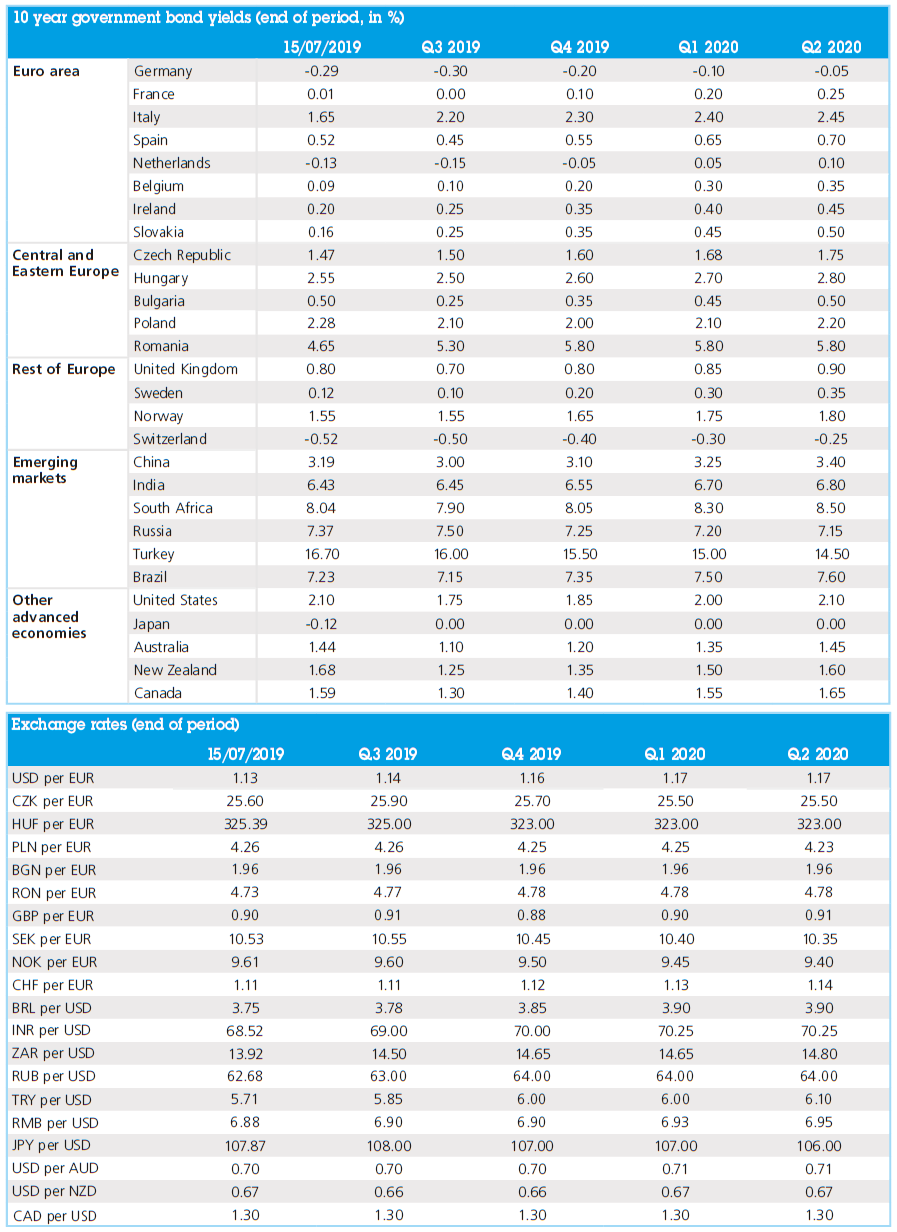

Waning business sentiment isn’t the only sign of weakness. Euro area consumer confidence dropped markedly in December as well but remains notably stronger than producer confidence. Continued job creation and rising wages are clearly supporting consumer sentiment. Hard data have been similarly disappointing: Industrial production in November declined notably in Germany (-1.9% m/m), France (-1.3% m/m), Italy (-1.6% m/m) and Spain (-1.5% m/m).

Figure 2: Industrial production, 12-month rolling average, yoy % change

The deterioration in manufacturing sentiment and industrial production is consistent with a less favourable global trade environment as uncertainty surrounding the US-China trade war persists. So far, the temporary ceasefire between the US and China has not yet led to an agreement to de-escalate the trade conflict. Furthermore, as mentioned in last months’ Economic Perspectives, temporary factors in the European automotive industry have been weighing on growth since September, and particularly on German output. Though these factors are fading, they likely continued to depress growth through the end of last year.

After a particularly weak Q3 2018, the most recent data suggest that final figures for Q4 will not see a strong rebound in the euro area. Indeed, recently published official growth estimates for Germany in 2018 confirm our expectations that while the German economy recovered somewhat in Q4, the recovery was tepid at best. As a result, we have downgraded our estimate for average annual GDP growth in 2018 from 1.9% to 1.8%. Higher uncertainty and the deterioration in both consumer and business sentiment will present a headwind to euro area growth in early 2019 as well. On a global level, concerns surrounding Brexit and the global trade environment will contribute to this uncertainty. At the more local level, the ongoing ‘gilets jaunes’ protests in France are already weighing on confidence and growth, with no sign of a quick resolution. Rather, the social unrest seems to be spreading to other European countries. Italy faces unresolved structural issues as well. Though the Italian government and European Commission reached a deal for a planned Italian budget deficit of 2.04% of GDP in 2019, the budget issue can be expected to resurface again later this year. Given these headwinds, we have also downgraded our forecast for 2019 GDP growth in the euro area slightly to 1.5%. Despite the weaker outlook for the Eurozone, the picture isn’t all bad. The economy is still expected to post a pace of growth in line with its potential or sustainable rate. Furthermore, the unemployment rate in the euro area is at post-crisis lows and continues to fall. Tighter labour markets across Europe should continue to support higher wages and in turn, consumer spending.

Soft, but not smooth Brexit

While a range of indicators suggest the UK economy is seeing some negative impact in areas such as consumer sentiment, home-buying and business investment from Brexit related uncertainty, growth has remained modestly positive if slower of late. The outlook for the coming year is very unclear because of continuing uncertainty about the timing and manner of the UK’s proposed departure from the EU. Following the crushing defeat in the UK parliament of the deal agreed between Prime Minister, Theresa May and the EU, the default option is that the UK is now scheduled to leave the EU on the 29th of March without any exit deal. Financial markets strongly hold the view that this will not happen as there is a majority within the UK parliament opposed to a ‘no deal’ Brexit. The problem is that there also appears to be a majority against all other proposed alternative options.

It is generally expected that the remaining EU 27 will agree to a temporary delay, meaning the UK will not ‘crash out’ of the EU at end March (The European Court of Justice ruled the UK can unilaterally revoke the Brexit process but only through an ‘unequivocal and unconditional’ decision, implying a delay must be agreed with the EU). However, the upcoming EU elections in May and the absence to this point of any workable proposals that could be agreed by the UK parliament are significant problems. Markets take the view that some sort of ‘fudge’ likely entailing a delay in Brexit will occur as there is a strong consensus that a ‘no deal’ Brexit will be extremely damaging to the UK and would also have a material negative effect on other EU economies- particularly given the recent weakening in growth momentum.

Expectations could change quickly and repeatedly because of notable difficulties in arriving at a workable compromise, meaning that the next month could see Brexit concerns causing further volatility. This bumpy path is broadly consistent with our long-held expectation of a ‘soft but not smooth’ Brexit process.

US growth remains on track despite a wobbly market

The US hasn’t managed to escape the downturn in sentiment either, despite being a stronghold in previous months. The ISM manufacturing survey dropped sharply in December to 54.1 from 59.3 in November. The recent increased volatility in financial markets also partially reflects concerns that the US economy may be past the peak of what has been a long and favourable economic cycle. The temporary inversion of the US yield curve in December was, for some, another harbinger of a coming deterioration in economic conditions. Yet, while economic growth is expected to decelerate in 2019 and 2020, the economy is still running well above potential. The labour market remains very tight and continued acceleration in wage growth should support household spending. As such, our expectations for average annual US GDP growth remain unchanged at 2.9% in 2018, 2.5% in 2019, and 2.0% in 2020, reflecting a moderate deceleration of a late-cyclical economy.

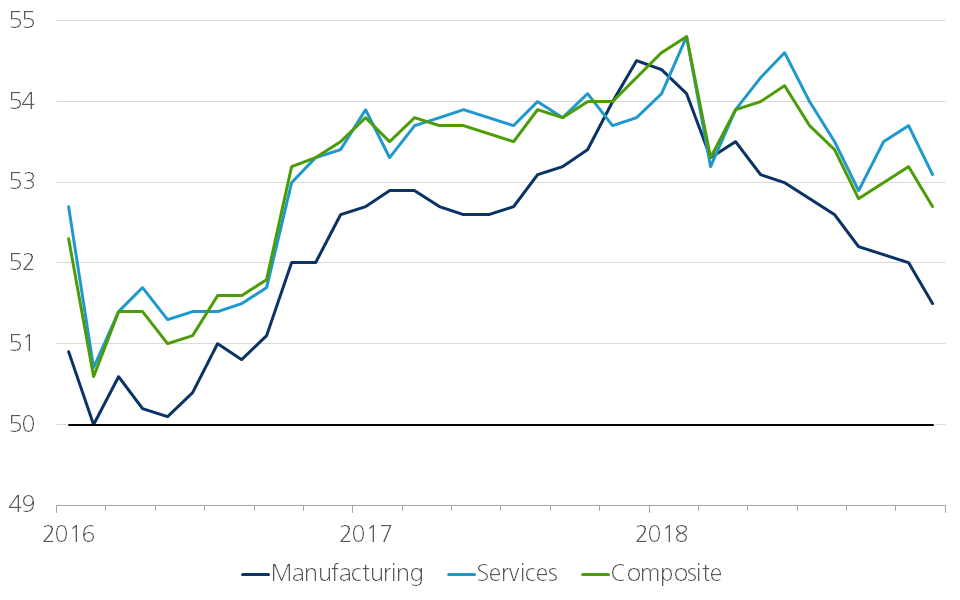

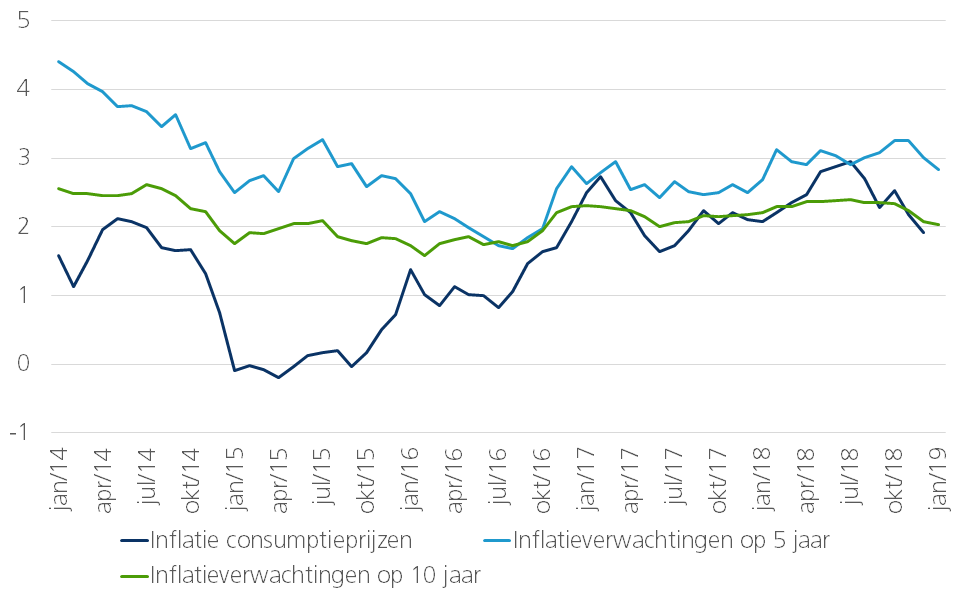

Despite above potential growth and rising wages, both actual inflation and inflation expectations in the US have come down, in line with the decline in oil prices.

Figure 3 - Realized and expected US inflation indicators (%)

With lower oil prices balancing out, to a degree, the predicted acceleration of core inflation due to a tight labour market, headline inflation is expected to moderate compared to 2018. We have therefore downgraded our average US inflation forecast (CPI) for 2019 to 2.2% y/y from 2.5% previously. With inflation expected to remain close to the Federal Reserve’s target, the US central bank will have less impetus for raising rates as aggressively as previously anticipated. We therefore bring our forecast for the path of monetary policy in the US in line with the median projection of Fed officials. Specifically, we now expect only two interest rate hikes in 2019 rather than four (see Box 1: The case for a less aggressive Fed).

Box 1: The case for a less aggressive Fed

Over the past several months, the outlook for the US economy has remained strong despite some rising risks. In contrast, the guidance coming from the Fed has clearly shifted in recent months from relatively hawkish to somewhat more accommodative. Indeed, Fed Chairman Powell went from suggesting that US interest rates were still ‘a long way from neutral’ in October to suggesting in January that a pause in the tightening cycle could be warranted. Market implied probabilities for the path of the Fed funds rate have similarly declined, with the market pricing in no further hikes in 2019 and the probability of a rate cut outweighing the probability of further hikes.

There may be several reasons for the shift in Powell’s tone. First, markets were clearly spooked by the prospect of an aggressively tightening Fed in 2019 as growth, though still above potential, is expected to decelerate going forward. Tighter financial conditions, and concerns over the removal of liquidity from the global economy in general has likely played a role in sparking increased financial market turbulence. Even comments by Powell on allowing the reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet to continue unchanged, prompted a slide in equity markets. Powell soon qualified those remarks, saying that the Fed ‘wouldn’t hesitate to make a change,’ regarding the balance sheet policy if conditions warranted it.

In addition to keeping an eye on market volatility, the change in Fed guidance likely also reflects a more subdued Fed outlook for headline inflation. Both realised inflation and inflation expectations in the US have come down recently, reflecting the recent decline in oil prices and an overall lower expected path for oil prices going forward. This is despite the still tight labour market which is expected to lead to further wage growth. With inflation expected to stay close to the Fed’s target, the central bank may indeed have more room to consider pausing, or even stopping, its hiking cycle earlier than previously anticipated.

Given the shift in guidance from Fed officials, and our new outlook for inflation, we now only expect two additional rate hikes in 2019 rather than four. We expect that the first hike will come in the first quarter and the second in Q3, with the Fed then ending its hiking cycle. There is downside risk, if sentiment continues to deteriorate, that the Fed may end its hiking cycle even earlier.

A number of downside risks to the outlook for the US economy have become more prominent of late. First, weakness in the international economy as evident in poorer readings for indicators from the Euro area to China, coupled with uncertainty about trade tensions are a constraint on US exports and capital spending (see box 2: Rising hopes for a trade war deal). Second, the impact of US tax cuts that boosted activity in 2018 looks set to fade. In its place, domestic policy difficulties as seen in the Federal Government shutdown could prove a headwind to growth. The ongoing partial shutdown is the longest in US history, and may threaten confidence the longer it persists. 800,000 government employees and an estimated 1.3 million contractors are currently going without pay, and several government agencies have temporarily cut back on most of their normal activities, which will have a ripple effect through the economy. Though during past US government shutdowns, the effect has only been temporary with most government workers (but not contractors) receiving back pay, the length of this shutdown is now unprecedented. The impact the shutdown may have on consumer and business confidence is a risk to watch going forward.

Box 2: Rising hopes for a trade war deal

The negative impact of the US-China trade war is beginning to filter through to the broader economy. Business sentiment is declining globally, weighed down heavily by weakness in manufacturing. In addition, the growth slowdown in China is contributing to increased anxiety about global economic conditions. The 3-month ‘cease-fire’ announced in December eased some tension temporarily, as the two sides agreed not to impose additional tariffs, but the veil of uncertainty was far from lifted. If no deal is reached between the two sides before 2nd of March, the US plans to increase tariffs on USD 200bn of imports from China from 10% to 25%. The Chinese authorities would likely retaliate, perhaps also with non-tariff measures, and the continued escalation of the conflict would have negative ramifications for global sentiment and growth.

The negotiations currently taking place between China and the US have provided some cause for optimism with the talks lasting longer than planned and a new round of trade talks expected in Washington. Given the growth slowdown in China, and increased financial market volatility in the US, both parties have an incentive to avoid further escalation of the conflict and instead reach a deal.

However, reaching such a deal remains very complicated. US demands, which include a reduction of its bilateral trade deficit with China, increased market access, better treatment of US companies in China, and a way to monitor the implementation of Chinese trade concessions, will be difficult for China to meet. Furthermore, structural issues related to technology and IP protection are far too complicated to be resolved in such a short time frame. As such, further escalation of the trade war remains an important downside risk to the global economy.

Finally, recent months have also seen tentative signs of a softer trend in housing related spending. The latest Fed Beige book summary of current economic conditions also suggested that while US growth is still solid, the pace may be easing and provided anecdotal evidence of increasing risks to the downside. For these reasons and, in circumstances where financial markets may be hinting that the Fed should be careful not to tighten too far, it is not entirely surprising that the words ‘caution’ and ‘patience’ have appeared more prominently in recent Fed comments.

Market volatility & safe haven flows

Despite the still generally positive outlook for the global economy, including growth at or above potential in most major advanced economies and tight labour markets that are leading to upward wage pressures, there is a rising sense of unease about economic conditions going forward (see also the Economic Opinion of 14 January 2019). This is reflected, in part, in sharply increased financial market turmoil in recent months entailing a marked rise in volatility. Oil price volatility as well, points to increased uncertainty about future demand (see Box 3: Lower oil prices and lower demand). These considerations mean increased caution is warranted.

Box 3: Lower oil prices and lower demand

The energy market has become markedly more volatile recently with Brent oil prices falling sharply from above USD 85 per barrel at the beginning of October to now stand at around USD 60 per barrel, having swung across a much wider range in the interim. The high volatility in oil markets is, to an extent, a reflection of the increased volatility seen in broader financial markets. As discussed in the main text, a downturn in sentiment, increased nervousness about a possible deterioration of economic conditions, the phasing out of unconventional monetary policy and a number of risks continuing to hang over the global economy are contributing to the higher volatility.

We have adjusted our outlook for oil prices slightly lower over the long term, with prices rising back only to USD 65 per barrel by the end of 2019 and then falling again towards USD 60 per barrel by the end of 2020. While there are some supply factors at play, the lower outlook overall, and specifically the decline in 2020, reflects lower demand as GDP growth slows globally. As such, lower oil prices are only partially an exogenous shock, and its ability to act as an economic stabiliser for the business cycle is therefore limited.

Global growth is expected to be lower in 2019 than in 2018, with slowdowns in the US, the euro area, and China. The ample liquidity associated with unconventional monetary policy appears under threat as central banks act on or talk about normalizing policy. At the same time, risks to the downside, which have been hanging over the global economy for some time, persist. Such risks include Brexit, the trade war rhetoric and measures of the US in particular, the growing global debt mountain, and concerns about the Italian economy.

As highlighted last month, it is not surprising, given the multitude of highly persistent downside risks, that investors continue to turn towards safe haven assets. German and US 10-year yields have fallen yet again, reflecting, in part, this flight to quality. The term-premium in Germany remains compressed, and the expected rise in long term yields that would be consistent with macroeconomic fundamentals has failed to materialize. With inflation expectations somewhat lower, the persistence of safe haven trends, and technical and policy factors at play that keep German bonds scarce, it becomes difficult to see a likely trigger that results in higher benchmark yields. We have therefore revised down our expectation for both US and German 10-year government bonds to 3.25% and 0.80% respectively for the end of 2019.