Economic Perspectives January 2020

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- After the global economic slowdown in 2019, 2020 starts with a slightly more positive economic outlook. Economic sentiment as well as activity data suggest some recovery in the global economy, although not all regions will evolve equally well.

- We confirm our scenario of a gradual recovery in the euro area economy in 2020. The manufacturing sector seems to have reached its trough in the fourth quarter of last year and a gradual recovery throughout 2020 is to be expected. Meanwhile, domestic demand and services remain resilient with limited spillovers from the manufacturing weakness. Unemployment rates remain very low in most European economies, while wage growth remains substantial despite the recent growth slowdown.

- Also in the US economy, economic developments are in line with expectations. In the context of global manufacturing weakness and an unfavourable, though somewhat improved, trade environment, US industry keeps on struggling. However, several positive signs in the US economy justify optimism. Private consumption is holding up well and we expect it to continue to be an important growth driver, supported by ongoing improvements in the US labour market.

- The economic outlook offers some support for current financial market optimism, although various risks may still affect the outlook. The signing of the US-China phase I trade deal makes further escalation of the US-China trade conflict unlikely in the short-term. However, several structural issues remain unresolved, which will likely cause more sparks of trade hostility going forward. Moreover, the risk of a direct confrontation between the EU and the US has become larger now after several recent political confrontations. The UK will leave the EU at the end of this month, but the trade negotiations that follow are likely to be bumpy as it is entirely unrealistic to envisage a comprehensive agreement can be reached by the end of this year. Also geopolitical tensions persist. We don’t expect the recent US-Iran conflict to escalate into a full-blown military confrontation. However, the intrinsic instability of the Middle East may cause volatility in financial markets in the future.

- This environment makes it likely that major central banks will remain on hold. There were some patchy signs that inflation in the euro area and the US might be picking up somewhat in recent months, but it is too early to speak of any sustained increase in underlying inflationary pressures.

Euro area scenario confirmed

Recent weeks brought few surprises in the latest data on the euro area economy. Revised GDP growth data were not materially different from earlier releases. Corporate sentiment indicators are meanwhile confirming our scenario of stabilisation with early signs of improvements in the manufacturing sector. In particular PMIs are illustrating this, while improvements are less visible in the Economic Sentiment Indicator from the European Commission. Though corporate pessimism still dominates in the manufacturing sector, the earlier downward trend in confidence seems to have halted in most of the euro area economies. The main exception to this is the Italian economy, where business sentiment continues to decline and activity remains weak.

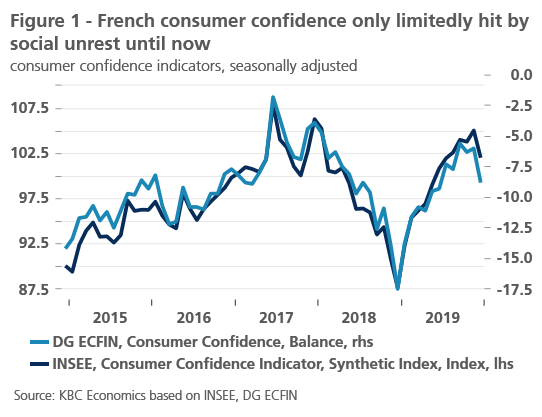

Meanwhile, private consumption continues to be resilient. Consumer confidence, though slightly down in recent months, is still at favourable levels. One country worth highlighting is France. In the context of social unrest and persistent strikes as a reaction to the pension reforms (also see KBC Economic Perspectives of December 2019), consumer confidence has only gone down marginally (figure 1). Compared to the slump at the end of 2018 due to the yellow vest protest, this recent downturn is very limited. Nevertheless, the longer social unrest persists, the higher the likelihood of a more severe effect on general economic sentiment in France. For now, we don’t think there will be a material impact on the French growth outlook but we will keep monitoring the situation closely.

Drawing together these elements leaves us with unchanged growth forecasts for the euro area as a whole. Real GDP growth in 2020 is expected to recover from the 2019 weakness on a quarterly basis, but annual average growth will remain muted and slightly below potential growth at 1.0%. The recovery in euro area quarterly growth will be largely driven by the expected recovery in the German economy. Since we’re at the start of a new year, our forecast horizon has also shifted forward. Looking to 2021, we expect annual average real GDP growth in the euro area to be somewhat stronger than this year (1.3%). These figures are corrected for any leap year effects (also see Box 1). Private consumption will remain an important growth driver.

Box 1 - Leap year, a boost for growth?

2020 is a leap year: it numbers 366 days instead of 365. Of course, this will have economic consequences as there will be one additional day for consumption and production. In a leap year these are therefore automatically higher than in the previous year, at least if all other circumstances are the same. The latter is never the case in practice. But the leap day does have the consequence that the growth rate of the economy in a leap year is mechanically boosted relative to the previous year. Similarly, this mechanical effect is reversed for the growth rate of the year following a leap year.

At first sight, such an impact does not seem very important. But one extra day on 365 means an increase of rounded 0.3%. In reality, the theoretical impact is larger, because it is not the number of calendar days that is relevant, but the number of working days. This is not only determined by leap year effects, but also, and more importantly, by the statutory regulation of normal working days and public holidays. This differs from country to country and may even differ from region to region within countries. The latter is, for example, the case in Germany. The impact on the number of working days also varies from year to year, depending on the coincidence between public holidays and weekly rest days. In the euro area countries, there are on average about 250 working days a year. The "growth effect" of one extra day is then already 0.4%. However, the exact number of working days varies from year to year, sometimes by two to three or even more days. In Germany, for example, there will be 251.5 working days in 2020, compared to 247.8 working days in 2019 (source: ECB). This represents a "growth" of 0.9%. If the economy were growing at a rate of 4 to 5%, that wouldn’t make a huge difference. But with the current growth rates in most euro area countries of 1% or less, such differences are more than a drop in the well.

Of course, this mechanical growth effect is not one that most economic analysis is interested in. It looks for the real pulse of the economy. In order to measure it, it is important that the analysis is based on figures corrected for the number of working days. This is the case for most quarterly gross domestic product (GDP) figures, which serve as the basis for calculating economic growth.

Where possible, KBC Economics only uses workday corrected figures in its analyses, publications and forecasts. This is a common practice in economic analysis which allows for the most accurate description of the strength or weakness of economic dynamics. However, growth figures also circulate on the basis of time series not corrected for the number of calendar days. For example, the quarterly GDP series published by Eurostat are adjusted for the number of calendar days, but the Eurostat annual series are not. The annual series use an accounting rather than an economic approach. Therefore, when comparing growth rates from different sources, it is important to bear in mind what adjustments the figures have or have not undergone.

In terms of risk factors, the picture for the euro area is dominated by threats to the downside. A further escalation of the US-China trade war is now less likely given the partial deal that was recently reached. Although the majority of tariffs between the two countries remain in place, the agreement reduces the trade uncertainties that companies face. However, a better US-China relationship does not guarantee a more favourable international environment for the European economy as the EU is increasingly becoming the target of more assertive trade policies by both superpowers (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 18 December 2019). The risk of a direct trade confrontation between the EU and the US is high on our watchlist because of its high probability and potentially severe economic impact in the euro area and in particular Germany.

The UK will formally leave the EU by the end of January but, with a transition period agreed to end 2020, the immediate threat of a no-deal Brexit has gone. Nevertheless, given the fact that the ensuing trade negotiations will likely be turbulent and structural damage that has been done to the UK economy, Brexit troubles are likely to cast a lasting shadow on the euro area economy going forward.

UK: uncertainty far from gone

Although recent Brexit developments have prompted short term relief, the latest economic data releases suggest UK growth is still weak and unbalanced. With expectations for some temporary pick-up in sentiment and spending as Brexit moves out of the headlines, a significant fiscal stimulus promised and the direction of negotiations between the UK and EU unclear, the Bank of England may opt to remain on the sidelines rather than implement a pre-emptive rate cut. However, elevated uncertainty will likely remain a feature of the UK economy and related policy decisions in the months ahead.

The substantial majority won by Boris Johnson in the recent British election emphasises the extent to which the population at large now simply wants to ‘get Brexit done’. It also removes the key obstacle a previously fractured parliament presented to UK government decision-making. Finally, it also means the new Government is fully committed to Brexit. These developments will likely materially change the complexion of UK/EU negotiations. They make it very likely that the UK will adhere to the commitment not to extend the transition period beyond the end of 2020 (although a short technical extension may be possible). In turn, this makes it likely that any agreement between the UK and EU is ‘narrow and shallow’ rather than wide reaching. This implies a ‘bare-bones’ deal on trade in goods with very little coverage of services.

US industry struggling

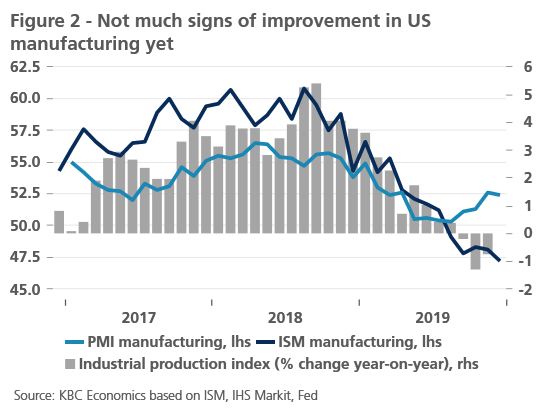

A divergence between the services and manufacturing sectors remains a feature of the US economic picture. Corporate sentiment in the domestically-oriented services sectors is again trending upward while manufacturing shows little sign of improvement (figure 2). Industrial production has also been weak over the past few months. An element that could be an additional drag on the sector’s activity in Q1 2020 is the Boeing 737 Max production halt. Though the importance of the company in the total US economy is rather small, via indirect effects on suppliers there will likely be a - albeit muted - impact on Q1 GDP growth. This will only partially be offset by the end of the strikes at General Motors. Hence, we adjusted slightly downwardly our growth forecasts for Q1, but this didn’t have an impact on our annual average growth figure. Therefore, we stick to our scenario with 1.7% real GDP growth in 2020. For 2021 we expect the growth pace to be roughly similar.

The unchanged scenario also remains underpinned by recent positive elements in the US economy. Retail sales and consumer confidence are holding up well, supported by still favourable developments in the labour market. Job creation has slowed throughout 2019, with rather disappointing payroll gains in December, but nevertheless remains reasonably solid. The unemployment rate held steady in the December reading to stand at 3.5%, maintaining the lowest level since 1969. These data suggest we may be approaching, or are at full employment. However, disappointing wage growth figures, with average hourly earnings growth falling below 3% yoy, are signalling otherwise and suggest that the unemployment rate isn’t showing the full picture of the US labour market.

Looking at other indicators, there might be some room left for further jobs growth. The prime age (25-64y) employment to population ratio has recently reached the pre-crisis peak, but is below what was seen in the 1990s. Moreover, the prime age participation rate has moved up since its trough in 2015 but remains below both the pre-crisis average and what was seen in the 1990s. If we consider labour force flows, the net figure of people moving from unemployed to employed less unemployed to not in the labour force turned positive in 2016 as has remained positive since. Additionally, the net figure of people moving from not in the labour force to employed less not in the labour force to unemployed reached its pre-crisis peak in late 2016 and has continued to surpass this level since. A longer view of these data suggests that there is scope for both to remain in positive, and possibly increasing, territory for some time. As the prime age labour force participation rate remains somewhat weak, there is likely room for further solid payrolls growth. This will support consumer spending power going forward.

Geopolitical turmoil, no lasting impact

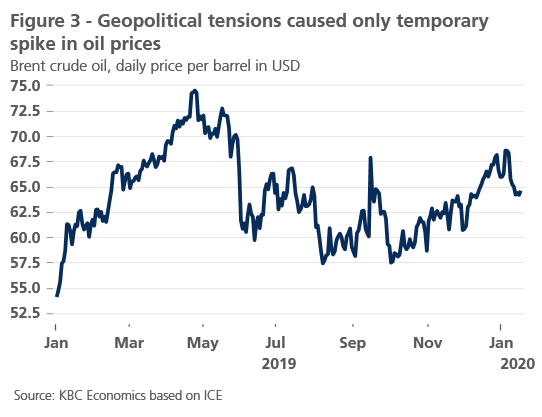

Global financial markets were spooked by the spike in hostility between the US and Iran at the start of the year (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 10 January 2020). Worries were, however, short-lived as US President Trump rather quickly cooled down tensions. Hence, the probability of an escalation of the military conflict has reduced. Following the attacks, the oil price jumped up to more than USD 70 per barrel of crude Brent oil, reflecting a spike in the geopolitical risk premium. As tensions abated relatively fast and there was no permanent disruption to oil supplies, the oil price shock was only temporary (figure 3).

Therefore, there will be no major impact on inflation figures, nor on (potential) GDP (see also Box 2). Nevertheless, the upward move in oil prices is not something new and has been seen since several months now. This has been due to the oil production cuts agreed by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in December 2019 that keep oil supply relatively contained.

Box 2 - Not all shocks are the same…

The recent surge of geopolitical tensions in the Middle East coincided with a spike of oil prices above 70 USD per Barrel Brent. What impact do economic shocks in general have on our scenario of economic growth and inflation? To make a correct analysis, we need to assess three characteristics: identification, magnitude and persistence.

Identification

In general, increasing oil prices are unambiguously associated with higher headline inflation. The link with economic growth is less clear-cut: it may be higher or lower. It really depends on the fundamental reason why oil prices are increasing.

To get the analysis right, it is important to assess whether higher oil prices are really the origin of the occurring economic shock, or whether they are themselves rather the consequence of another shock that occurred in the ‘background’. Are they the result of an independent (exogenous) shock to the economy, e.g. due disruptions through political events such as war? In this scenario, higher oil process are probably associated with decelerating economic growth. Or is the increasing oil price simply an automatic (endogenous) response to another economic shock? For example, improving sentiment may accelerate economic growth, which in turn may also lead to higher demand for energy and hence also to higher oil prices. The economic characteristics of both scenarios is very different.

Magnitude

In order to have an analytical framework, economists often think of the economy as a system that operates on an ‘equilibrium’ path unless it is pushed away from this path by an external ‘shock’. As this shock ends, the economy will gradually return to its equilibrium path. These shocks can differ both in terms of their magnitude and their persistence. Obviously, a stronger shock causes a stronger deviation of the economy from its ‘normal’ equilibrium path than a weaker one. The transition period to return to the equilibrium path after the shock has ended will also last longer, other things being equal. Whatever the magnitude of such a shock, the economy will normally return to its original equilibrium path, in some cases after a catch-up phase of the economic cycle.

Temporary versus permanent

Next to their magnitude, the persistence of economic shocks plays at least an equally important role. First, by their very nature, permanent shocks have a longer-lasting impact than temporary ones and hence a larger impact on the economy, other things being equal. Second, permanent shocks are also more likely to structurally change the equilibrium path of the economy in the long-run. For example, a permanent upward oil price shock may affect the long run potential real GDP growth rate of an economy (i.e. a negative supply shock), while a temporary shock will probably not. Third, a permanent shock may also affect expectations by economic agents, thereby creating an additional transmission channel to the economy. In the example of a permanent upward oil price shock, inflation expectations are likely to adjust upward as well, becoming self-fulfilling by feeding through into nominal wage negotiations (the so-called second round effects). If left unchecked, this effect would exacerbate the impact of the original shock on economic growth (downward) and inflation (upward). In order to prevent inflation expectations from spiralling up, central banks are therefore likely to respond to this permanent shock by tightening monetary policy, dampening economic growth even further. In case of a temporary shock, with no or little impact on inflation expectations, central banks are more likely to adopt a wait-and-see stance.

Application to our economic scenario

Applying this framework to the latest spike of oil prices, our assessment is that its magnitude is quite moderate and, more importantly, of a temporary nature. As a result, its impact on our economic scenario has been quite limited. However, we continuously monitor every parameter mentioned above, since they might change their nature quickly over time.

At the end of Q1 2020, the oil price is likely to remain somewhat elevated at USD 65 per barrel Brent due to more aggressive than expected production cuts by OPEC in Dec. 2019, some easing of the Sino-US trade tensions and an elevated geopolitical risk premium (which is probably overshooting). The oil price will moderate to USD 60 again from Q2 2020 on as high price sensitivity of shale oil production, which, from Q2 2020 on, will likely also offset the OPEC production cuts currently in place, as OPEC members are unlikely to fully comply with their agreed quota and as OPEC production cuts are unlikely to compensate for non-OPEC production growth in 2020. The risks to the oil price scenario are broadly balanced. A structural break in oil supply – e.g. caused by attack(s) on major oil installations – would cause the oil price to increase more permanently. While a renewed oil supply glut in case of no extension of the OPEC production quota would weigh on oil prices.

Euro area inflation seemingly rising

Euro area headline and core inflation rose to 1.3% yoy in December 2019. The increase was mainly driven by a larger contribution from food and services prices in recent months. This price evolution may owe something to the evolution of wages in the euro area. Due to increasing labour market tightness in many European countries, annual wage growth rose to 2.61% in the third quarter of 2019 (ECB figures). Higher wages generally seep through more strongly and faster into service prices, which seems to be the case in recent data. This is a structural form of inflation, for which we - and the ECB in particular - have been waiting for a long time. Also underlying the rise in services inflation were increased prices of holiday packages, which is a quite volatile component and may reflect technical changes in the measurement process rather than any marked build-up in price pressures in this area. Besides services and food prices, energy prices also again contributed positively to headline inflation as global oil prices climbed. It remains to be seen whether the recent modest upward move in euro area inflation is sustained.

In any case, the ECB’s inflation target of around but just below 2% is still a long way away from current inflation readings. Therefore, we don’t expect the ECB to change its monetary policy stance any time soon. In this context together with the envisaged economic developments, we expect German 10y bond yields to increase gradually throughout 2020-21, similar to the expected yield evolution in the US. This gradual normalisation of long term interest rates is still subject to risks. Negative news on the trade war or Brexit might lead to a temporary fall back in interest rates. On the other hand, more positive economic news or a structural change in monetary policy targets, as a result of the ongoing monetary policy evaluations at the Fed and ECB, might result in a faster than expected yield normalization. Hence uncertainty in terms of the evolution of interest rates persists.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date, up to and including 13 January 2020, unless stated otherwise. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 13 January 2020.