Economic Perspectives February 2020

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF

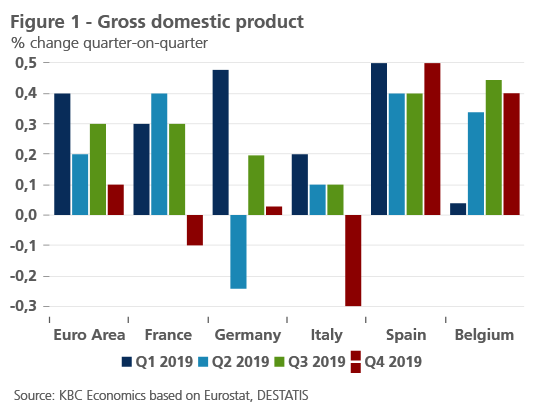

- For the euro area as a whole, the incoming data support our view of a gradual growth recovery in the course of this year. Consumption demand remains resilient and although it’s too early to speak of a sharp recovery, industrial sentiment indicators are showing signs of stabilization. However, the euro area economy remains a mixed bag with upside and downside surprises in Q4 real GDP growth figures across countries.

- The US economy continues to perform well, and even slightly better than expected. Q4 GDP growth was pushed up by a marked decline in US imports, but consumption of domestic goods and in particular services is holding up well. Since the prospects for the US labour market are still favourable, private consumption will continue to be the main growth driver.

- The outbreak of the coronavirus means a new headwind for the Chinese economy, which seemed to be doing better at the start of this year. The magnitude of the economic impact of the epidemic is hard to estimate given that we don’t know yet how quickly the virus will be contained. However, assuming that the peak of the virus will be reached before the end of the first quarter, the economic blow will likely be temporary and a normalisation after the dip is likely. Moreover, it will be mainly China that will suffer economically as the macro-economic distortion to the global economy remains limited under this scenario. This outcome is nevertheless prone to a high degree of uncertainty. The risk that the disease spreads much more across the globe is not negligible. In that case, the negative impact on global economic growth would be much more severe.

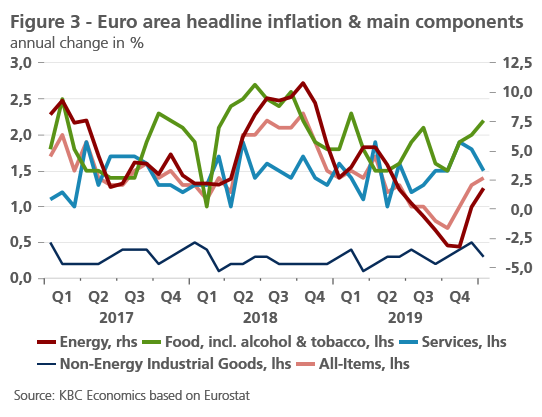

- The uptick in euro area inflation at the end of 2019, that has already partly been reversed, was mainly caused by volatile components. While there are some signs of rising wage growth translating into stronger inflationary dynamics – mainly in labour intensive services sectors with small weights in the overall inflation index – our overall scenario of very gradual inflation increases remains in place.

- Major central banks are expected to remain cautious going forward. However, the recent unexpected rate hike by the Czech National Bank signals that a gradual further normalisation of monetary policy in Central Europe is taking place.

Q4 surprised, scenario unchanged

Real GDP growth figures for Q4 2019 brought several upside as well as downside surprises in euro area countries. Disappointing results were released for Italy (-0.3% qoq) and France (-0.1% qoq) (figure 1). In Italy, there was a decrease in value added in agriculture and industry, while services stabilized. The combination of the significantly weaker-than-expected last quarter of 2019 and a slight downward adjustment of our Italian quarterly growth projection for Q1 2020 (from 0.1% qoq to 0.0% qoq), led to a downward adjustment of our 2020 annual average GDP growth forecast from 0.5% to 0.0%. In France, there was some negative impact from social unrest on growth, but also one-off factors were at work in Q4. The exceptionally mild winter weather caused less consumption demand for heating. Moreover, inventories contributed sharply negatively to GDP growth as a consequence of de-stocking of aeronautical and naval equipment production from earlier quarters. Nevertheless, the disappointing Q4 figure hides continued underlying strength of the French economy, which is why we don’t think a major revision of our French growth projections is necessary.

On the other hand, real GDP growth in the fourth quarter was better than we anticipated for Spain (+0.5% qoq) as somewhat weaker domestic demand was compensated by stronger exports. Belgian (+0.4% qoq) and German (0.0% qoq) real GDP growth also surprised to the upside. Though somewhat better than we anticipated, German real GDP growth in Q4 was weaker than in Q3 (+0.2% qoq) as a result of a slowdown in both household and government expenditures according to preliminary figures. Net exports contributed negatively to GDP growth in Q4 as exports slightly decreased while German imports rose compared to the previous quarter. Investments showed a mixed picture, with a marked decrease for machinery and equipment – related to the weakness in German industrial sectors. Meanwhile, investment in construction increased. On balance, Q4 real GDP growth for the euro area as a whole was in line with our expectations (+0.1% qoq), resulting in an annual average growth rate of 1.2% for 2019.

High-frequency indicators paint a broadly similar picture as in previous months. Sentiment indicators don’t show any material change. There are persistent signs of stabilization of corporate sentiment, now not only in the PMI’s but also better visible in European Commission’s Indicator. Solid levels are still being reported in France, despite some weakening. Recent social unrest and public strikes hence don’t seem to impact economic sentiment as sharply as was the case during the yellow vest protests at the end of 2018. An important point of weakness in the euro area remains Italy, where weakness in sentiment and activity data persists despite the favourable results of regional elections for the current government coalition. Industrial activity indicators are showing some improvement in the euro area, but it is too early to talk of a strong general recovery, particularly as Germany industrial production continued to shrink. Meanwhile, consumption demand remains resilient supported by strong labour market performance.

Therefore, despite some surprising Q4 GDP figures in the underlying country data, we did not change our annual average GDP growth forecasts for the euro area. Growth will remain rather muted this year, but will recover on a quarterly basis, resulting in an average annual growth of 1.0% this year and 1.3% next year. We assume that the negative impact of the coronavirus and associated measures on euro area growth will be mild and temporary, mainly concentrated in the first half of the year (also see below).

Steady US growth

The US economy reported slightly stronger-than-expected real GDP growth in Q4 2019 (+2.1% qoq annualised). This was a steady growth pace compared to the previous quarter, but underlying growth details showed some signs of weakness in investment and personal consumption. The headline growth figure was also boosted by the largest drop in imports since 2009, leading to a positive growth contribution of net exports. On balance, this means that US consumers are consuming less, which is mostly absorbed by lower imports, while consumption of domestic services remains strong. The slowdown in annual retail sales growth - to 3.5% in 2019 from 4.8% in 2018 - underscores this weakness in (foreign) goods consumption as well. One potential explanation for this are anticipatory imports of consumer goods into the US in earlier quarters. The likely trigger for this was the threat of new US import tariffs on imports from China that were partly implemented in September 2019. As a consequence, US inventories of Chinese consumer products were high at the start of Q4 and were drawn down in the course of the quarter. This also is consistent with the drawdown in inventories that we saw in Q4. Meanwhile, consumer sentiment remains solid despite some monthly choppiness. Therefore, despite the declining GDP growth contribution of private consumption, the underlying message about US consumers still remains positive.

Corporate confidence is improving again as the four main business sentiment indicators are now back in expansion territory. The latest uptick was likely also driven by the signing of the US-China trade deal (also see Box 1). However, there continue to be challenges ahead, in particular for the US industrial sector. Industrial production continues its year-on-year declines. Moreover, the Boeing production halt will weigh down on production as well. The negative impact of the coronavirus is expected to remain mild (also see below), but the risk of more severe economic damage increases the longer it takes to contain the virus outbreak.

Box 1 – Feasibility of Chinese import commitments in US-China trade deal is questionable

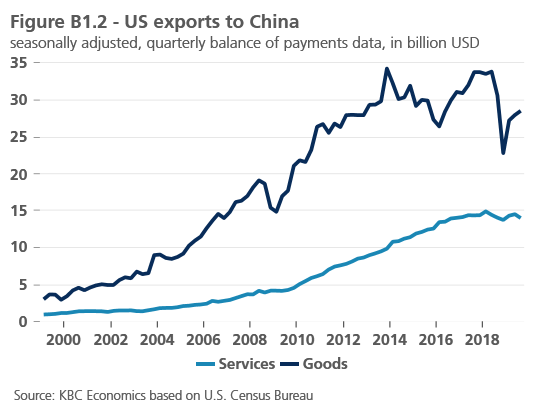

The “phase one” trade deal between the US and China that was signed mid-January will go into effect from this month on. One important element of the trade agreement is the set of import commitments China agreed to. US exports to China have been much smaller than US imports from the country. The difference between the two, the US-China bilateral trade balance, has hence been negative and this deficit has even been growing over time. In order to reverse that trend, China committed to increase its imports from the US by at least USD 200 billion, compared to total Chinese imports from the US in 2017, over the course of this and next year (figure B1.1). The phase one deal contains a more detailed plan to achieve this. In terms of subcategories it implies an increase of imports worth USD 77.7 billion for manufactured goods, USD 32.0 billion for agricultural goods, USD 52.4 billion for energy products and USD 37.9 billion for services, spread over two years’ time.

The commitments are sizable and the feasibility of them can be questioned for several reasons. For one, the mentioned import increases are benchmarked to 2017 data flows. According to US data, the US exported roughly USD 130 billion of goods and USD 57 billion of services to China in 2017. Comparing these figures to the Chinese import commitments in the phase one trade deal, this would imply that over the course of this and next year together, Chinese imports of goods and services from the US would have to more than double. Moreover, as a consequence of rising trade tensions between the US and China, export flows from the US to China have declined in the past few years (figure B1.2). This is in particular the case for trade in goods. Hence, compared to trade flows in 2019, the Chinese import commitments are even larger. Since most tariffs that were implemented in China and the US in recent years are – despite some minor rollback – not reversed by the US-China trade deal, such a sharp recovery of bilateral trade is not very likely.

Furthermore, assuming that China did stick to its commitments, Chinese imports would very likely be directed away from its other trading partners. After all, the Chinese economy is going through a transition towards lower-quantity and higher-quality growth. Hence, a steep rise in its total demand and imports is unlikely. Significantly higher Chinese imports from the US would therefore likely result in lower imports from other countries.

It is also questionable whether US companies will be able to increase their production to export more to China. Given capacity constraints and the late-cyclical stage of the US economy, this might not be fully feasible. In that case, the US-China bilateral trade balance might become less negative, but bilateral trade balances with other US trading partners might worsen, meaning no major improvement in the US’s total trade balance.

In our view, the feasibility of the Chinese import commitments in the US-China trade deal is hence questionable. Especially in the short-term, the Chinese measures taken to contain the spread of the coronavirus might complicate the compliance further. Furthermore, the consequences might reach much further than only the US and Chinese economies. It remains to be seen how many of the promises made in the deal will be redeemed.

To summarise, our real GDP forecasts for the US economy didn’t change compared to last month. We still project annual growth to reach 1.7% in both this and next year. Private consumption is expected to remain the most important driver. It will be underpinned by favourable labour market dynamics since comments by the Federal Reserve suggest a willingness to ensure maximum employment.

Poor timing for China

Before the coronavirus outbreak became headline news, a string of positive Chinese data was suggesting that the government’s previous stimulus efforts were having some effect. Business sentiment in the manufacturing industry has recovered to expansionary territory while sentiment in the services industry is still strong. Industrial production growth is showing signs of stabilization, as is fixed asset investment in the industrial sector. What’s more, the signing of a phase one trade deal with the US, removes some of the headwinds that have been dragging on the Chinese economy. While the trade war was not the sole driver of the slowdown, it increased uncertainty, weighed on sentiment, and likely had some negative impact on China’s manufacturing industry and foreign trade.

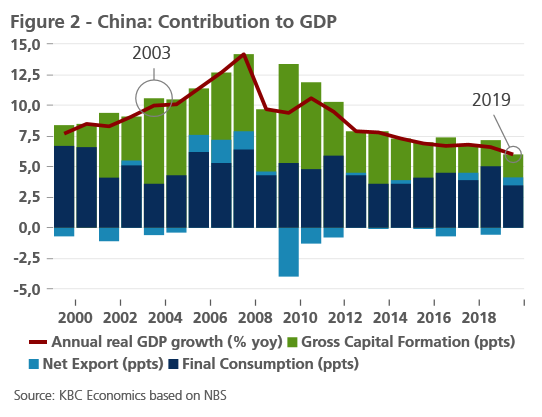

Unfortunately, that good news has now been overshadowed by the outbreak of the coronavirus. As seen with the SARS outbreak in 2003, the macroeconomic effects of an epidemic can be sizeable. The magnitude of the corona impact is hard to estimate given that we don’t yet know how quickly the virus will be contained. But hits to tourism, transport, retail, and general consumer demand in areas directly affected by the virus are already being seen. Mild, second round effects on China’s trade partners due to weaker Chinese demand are also possible. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that there will be some, at least temporary, drag on Chinese growth.

Consumption and travel will likely normalise once the outbreak of the virus is under control. However, given the current timing around the Chinese New Year celebrations, there will likely not be a compensating ‘excess of spending’ such as additional eating or travelling later in the year. Hence, once the shock has ended, the earlier losses won’t be fully compensated. Though industrial production will also recover again after the temporary effects fade out, also firms are not very likely to go much further and compensate fully for earlier lost production. After all, the Chinese economy is going through a longer-term process of slower but better-quality growth. Moreover, global economic growth is expected to remain rather muted this year. Besides, a key issue is the extent to which Chinese fiscal policy is loosened and/or monetary measures boost demand. China is already facing elevated inflation driven by food prices and high indebtedness of both the corporate sector and households. Furthermore, the share of consumption in Chinese GDP growth has become much larger relative to the importance of investments (figure 2). Therefore, we don’t expect the Chinese authorities to massively intervene to artificially ramp up growth via investments as was the case following the SARS outbreak in 2003.

Based on these arguments, we expect Chinese growth to slow down considerably in Q1, followed by a partial recovery in Q2 and an even stronger recovery in Q3. On an annual basis, we downwardly revise our outlook for Chinese real annual GDP growth in 2020 from 5.7% to 5.2%.

Our scenario assumes that the coronavirus remains largely contained within China in terms of mass cases and fatalities. The lockdown of the city of Wuhan, the Chinese city where the first cases of corona popped up, together with the lockdown of some other economically important cities in China, probably helped in limiting the spreading of the virus and hence underpins this view (also see Box 2). Of course, these projections are subject to a high degree of uncertainty. The risk that the disease spreads much more toward the US, Europe or other areas in the world is not negligible. In that case, the negative impact on economic growth across the globe would be much more severe. For now, we mildly change the quarterly growth dynamics for the euro area and US. However, these quarterly changes have no impact on our annual growth forecasts for the euro area and the US.

Box 2 – Wuhan: much more than just the place where the coronavirus broke out

Wuhan and dorona. These two concepts have become inextricably linked over the past few weeks. The number of infections continues to rise daily and the number of deaths rose to more than 1000, making the coronavirus more deadly than the SARS epidemic that broke out in 2002-2003. For China, however, Wuhan - the capital of Hubei province - is much more than just the place where the virus broke out. Wuhan is a logistics hub, also known as “the Passage of China”. The city with about as many inhabitants as Belgium contains crucial transport channels by road, air, water (Wuhan is located at the junction of the Yangtze and Han rivers) and rail. This extensive transport network makes Wuhan very attractive to companies. It is in particular popular among industrial firms (automotive, steel and chemical), although the metropolis has been welcoming more and more technology companies in recent years.

The city - and the province – have been able to benefit from its strategic location. Wuhan became an important economic engine. Economic growth reached 7.8% in 2019. In comparison, total Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 6.1% last year. The city accounts for more than 60% of Hubei province’s foreign trade (244 billion yuan, some 32 billion euros). Hubei’s economic importance in turn also increases year after year. The share of Chinese GDP is steadily increasing: from 3.2% in 2007 to 4.3% in 2019. The province is thus the seventh most important in China’s total GDP. Expressed in terms of investments, the picture looks even more impressive. 7.5% of total Chinese capital expenditure is accounted for by Hubei, compared to approximately 3.5% in 2007.

Volatile components driving inflation

The upswing of headline and especially core inflation in the euro area at the end of 2019 raised the question whether euro area inflationary dynamics were finally rising. However, the end-2019 upswing of core (services) inflation was more of a “false alarm”, mainly due to volatility, in particular coming from a change in the way German package holiday price inflation is calculated (figure 3). Indeed, core inflation already returned back towards its trend level (1.1% in January 2020). There are some signs of wage inflation feeding through in services inflation for labour intensive services though – e.g. for housing related services, recreation and personal care. However, these subsectors have a low weight in the overall inflation index. Moreover, productivity gains are tempering the impact of labour cost increases on inflation. Hence, overall, our scenario of only gradually increasing euro area inflation resulting from very gradually building wage pressures, with a moderating impact of energy prices in the short-term, remains intact.

Risks to headline inflation are tilted to the downside, especially in the context of the corona outbreak. In recent weeks, the negative demand impact from the corona epidemic on Chinese growth in Q1 2020 and the related (expected) fall in oil demand caused – aside from the unwinding of large speculative positions in Brent crude during the earlier upward price spike - a sharp drop in oil prices. If the epidemic turned out to be much more severe than currently assumed, the negative impact on oil demand and prices would be larger. As a consequence, this would drag down headline inflation across the globe further.

Long-term rates infected by corona, central banks on hold

Apart from declining oil prices, the coronavirus outbreak triggered a fall in long-term government bond rates too. The gradual global normalization path of long-term interest rates, that started late summer 2019, has been interrupted by the uncertainty and potential negative economic impact of the epidemic. However, we expect rates to continue their normalization path as soon as the virus outbreak gets under control.

Meanwhile, intra-EMU spreads remain very limited due to the ECB’s Asset Purchasing Programme. There has been a striking further drop in the Italian-German spread as an immediate political crisis has been averted after recent local elections.

The major central banks are expected to keep policy rates stable for the remainder of 2020. Only in case the coronavirus caused more international economic damage, central banks would likely intervene again.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date, up to and including 10 February 2020, unless stated otherwise. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 10 February 2020.