Does increased liquidity affect the European housing market?

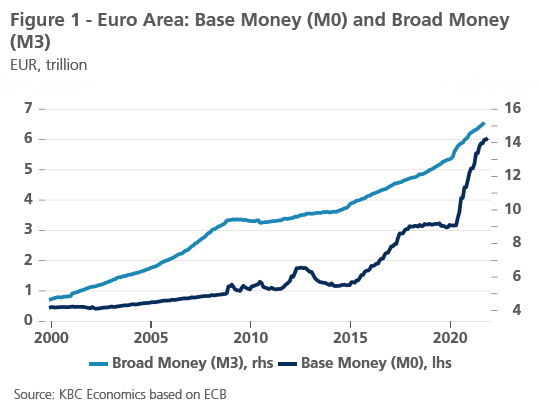

From a theoretical point of view, additional liquidity in the market can increase house prices through various channels. For example, loans may be taken out at more favourable terms and more households may have access to them. Rising house prices due to increasing demand for real estate also increase the collateral that can be used for a loan, which may further reinforce this effect. A generally stronger economic activity, supported by the available liquidity, can also push up rents, which again has an increasing effect on house prices. Figure 1 shows the evolution of base money and broad money in the euro area. We ask ourselves whether the recent increase in base money (M0), as a result of ECB’s quantitative easing, may be causing the eurozone housing market to be overvalued. We then compare the increase in broad money M3 over the past year with the one prior to 2008. We conclude by asking whether the eurozone housing market can be considered overvalued or not.

Housing market and base money

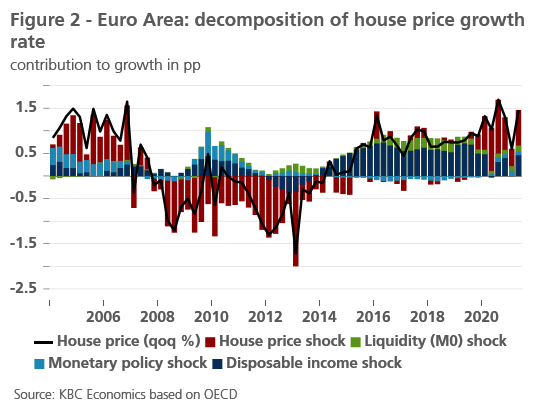

In Figure 2, using a structural BVAR model, we identify several economic ‘shocks’, unpredictable events that either positively or negatively affect euro area house price inflation. Later, we consider how the same shocks can affect the broad money supply M3, but first we focus on the impact of the recent increase in base money (i.e., the monetary base or M0).

A shock to disposable income (dark blue) increases the demand for property and will consequently make it more expensive. The contribution of monetary shocks is shown in light blue. Lower than expected short-term interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing and increase not only the demand for real estate (which positively influences house prices) but also that for other durable goods, which also increases money demand. Shown in red are the effects of the house price shock. This shock can be associated with other factors that increase the demand for real estate and its price, on top of the standard macroeconomic fundamentals. Such shocks are often associated with under- or overvaluation of the housing market, they increase house prices and consequently the borrowing capacity of homeowners, which can cause a rise in demand for credit and thus the money supply. A liquidity shock, shown in green, driven by ECB’s recent quantitative easing, measures the extent to which additional liquidity in the market - independent of the interest rate – is leading to additional price effects in the housing market.

As indicated in the introduction, there are theoretical reasons to expect an effect of liquidity shocks on house price inflation. Although other shocks contribute relatively more, liquidity shocks do have an effect on house price growth, as can be seen in Figure 2. When we calculate the cumulative effects on house prices, we obtain a total contribution of the liquidity shocks of 2% in the period 2020 - 2022, which is similar to the cumulative effect in 2015 - 2017 of the increase in M0. This calculation assumes no additional liquidity shocks than those already observed in the current and previous year.

Housing market and broad money

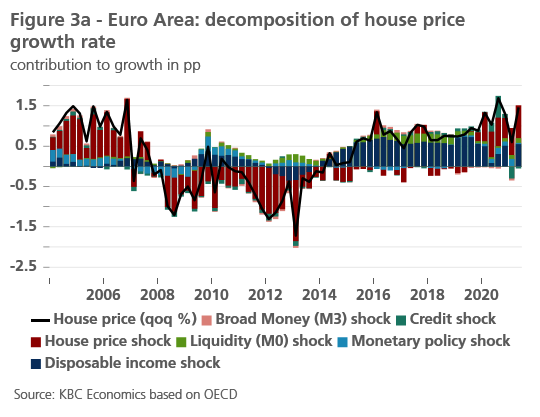

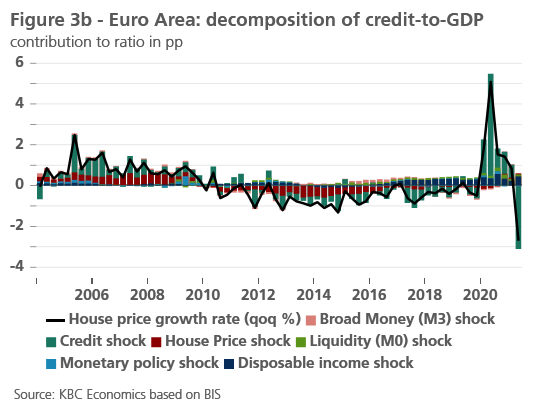

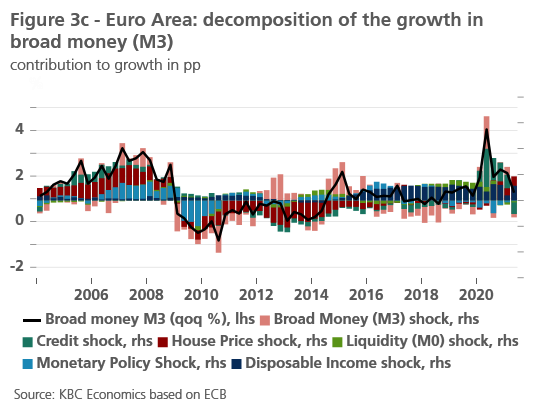

The creation of the housing bubble before 2008 went hand in hand with a rise in broad money (M3). Should we therefore be concerned about the recent rise in M3, observed in Figure 1? To analyse this, we extend our model with two variables, namely total credit provided to the non-financial private sector as a percentage of GDP and broad money (M3). We observe that credit growth (Figure 3b) in the years prior to 2008 was strongly driven by house price shocks, which we associate with under- or overvaluation of the housing market. We observe the same when we look at M3. The red house price shocks accounted for a large part of the growth in M3 in the years before 2008. Thus, the house price shocks are the reason for higher money supply and not the other way around. Correlations between house prices and M3, show that the house price is the leading variable. The strong credit shock of the past year, which was also largely responsible for the increase in the broad money, has only a limited effect on house prices. We can therefore conclude that the rise in M3, can be driven by several economic shocks. The current rise in M3, has a different cause than the one before 2008, a cause that is not symptomatic of an overvaluation of the housing market.

Is the housing market overvalued?

Of course, the euro area housing market is very heterogeneous and statements about under- or overvaluation could hide differences between countries. However, Figure 2 and 3a show house price shocks in 2020 and the first half of 2021. These changes in euro area house prices cannot be accounted for by fundamental shocks to the housing market and may thus indicate increasing overvaluation. In contrast, strong house price inflation in previous years was mainly driven by economic fundamentals.

Nevertheless, a few comments should be made. This simple model, designed to measure the effects of liquidity shocks on the housing market, does not include all fundamental variables. We should therefore be careful to consider this housing price shock entirely as an overvaluation. In addition, there is the unique nature of the corona crisis that must be considered. In this model, negative shocks to disposable income were obviously observable with each new corona wave. However, as expected, the effects of these shocks were short-lived, compared to historical shocks of the same type. Simply put, why should housing prices in an efficiently functioning market adjust to unexpected declines in disposable income as they did in the past, knowing that these declines are only very short-lived. A strong economic rebound together with a sustained favourable interest rate environment may cause the measured overvaluation to disappear on its own over the next few years. However, if house prices continue to rise faster than what fundamental shocks to the economy can justify, then we will have to watch out.

ECB’s valuation models also show an increase in the overvaluation of housing markets. Compared to the first quarter of 2020, the overvaluation in half of the EU countries was even 10% or higher in the first quarter of 2021. A warning the ECB repeated in its November Financial Stability Review. The IMF notes in its latest Global Financial Stability Report that for developed countries, compared to the years before covid-19, the fifth percentile of the house price growth distribution fell from -6% to -14%. Simply put, the probability of a correction has increased. However, the same remark about the specificity of the covid shock can also be made for these models.

In conclusion, the positive liquidity shocks of 2020, resulting from ECB’s quantitative easing, have a rather limited effect on European house prices in the model used. The recent rise in M3 is not symptomatic of a housing market bubble, as it was in 2008. The measured house price shocks (indicating possible overvaluation) can be partly explained by the specificity of the corona crisis and should not be interpreted as a generalised bubble or cause major concern at this stage. However, if house prices continue to rise more strongly than what we can expect from fundamentals in the coming quarters, we should revise this view and a correction in the housing market in the medium term will become likely. It is important to underline that this analysis does not rule out strong under- or overvaluations in specific euro area countries.