Debt, decoupling, and diversifying growth: China’s many challenges

Content table:

I. Introduction

II. Debt difficulties and risks

Real estate crisis textbook case of underlying risks

Financial stability parallels

III. Finding new engines of growthDual circulation agendaIV. Conclusion

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

I.Introduction

The Chinese economy has developed at an unprecedented pace over the last 30 years, becoming the world’s second largest economy and accounting for roughly fourteen percent of global trade. Much of this development can be attributed to the integration of China in the global economy against the backdrop of an abundance of cheap labour, significant investments in infrastructure and general catch-up growth. While growth has been trending lower for over a decade, China’s macroeconomic outlook has grown more complex in recent years as important headwinds continue to mount.

Over the past year in particular, economic developments in China have become increasingly turbulent, raising the question of whether China could be headed for a more serious crisis. While there are several headwinds — some of them structural in nature – that appear to be tipping the balance in that direction, there are important countervailing factors as well. Long-standing problems like an unbalanced economy with weak consumption, troubling demographic projections, and tensions with the West seem to be coming to a head with shorter term problems, like China’s covid policies (the ongoing reversal of which poses its own concerns), the crisis in the property sector, and new geopolitical tensions that accelerate US-China decoupling. In addition, China’s debt problems are not limited to the real estate sector, and risks related to Local Government Financing Vehicles appear to be increasing.

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. Despite China’s high debt levels, most of this debt is in local currency, and held locally, while external debt, when measured against income sources such as GDP or (net) exports, remains relatively limited.

China also has very strong policy levers it can rely on, including the ability to intervene, if necessary, should a more substantial crisis arise. Additionally, some progress has been made in terms of rebalancing growth, though challenges remain, and three years of strict covid policies have been a setback for that rebalancing. From a longer-term perspective, however, China’s dual circulation policy agenda is meant to address China’s unbalanced economic drivers at the same time that it protects China from the negative impacts of decoupling. Whether the (sometimes conflicting) goals of this policy can be achieved, however, remains to be seen. How these many headwinds and unanswered questions resolve themselves will help determine whether China can escape the middle-income trap and continue on the path toward convergence with high income economies, or whether it will face a long spate of below-potential growth, and possibly even a major crisis.

II.Debt difficulties and risks

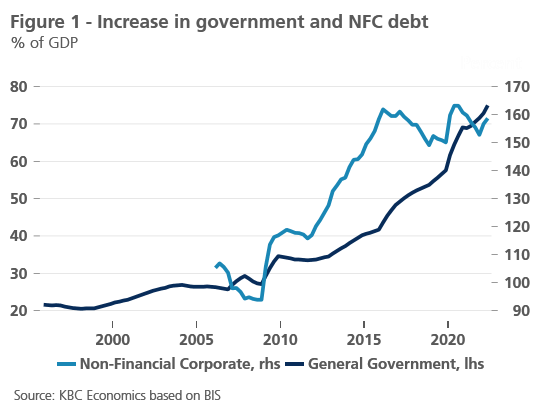

Many of China’s structural challenges (and resulting financial stability risks) stem from an overarching problem of too much debt that has built up in the economy. Debt-led and state-directed investment growth has supported China’s high growth rate and catch up for many years and has been relied on heavily in times of economic slowdowns to maintain stable growth and employment. This has particularly been the case since the global financial crisis, with government debt-to-GDP and non-financial corporate (NFC) sector debt-to-GDP increasing from 27% and 94%, respectively, in 2008, to 73% and 157%, respectively, as of Q1 2022 (figure 1). Meanwhile, household debt has also grown significantly, which is discussed below.

The growth in both government and NFC debt, however, is closely linked. In fact, much of the off-balance sheet debt of the local governments is recorded as corporate sector debt. As this raises questions of implicit guarantees and contingent liabilities, the IMF considers a non-augmented and augmented indicator of Chinese government debt, with augmented government debt being much higher (expected to have reached nearly 110% of GDP in 2022).

This debt-led investment model has become increasingly inefficient over time, with a higher increase in debt needed to achieve the same increase in nominal GDP. E.g., the ratio of the annual change in debt relative to the annual increase in nominal GDP averaged 1.8 between 1997-2008. In response to recent crises, that ratio reached 5.6 in 2009, 4.9 in 2015 and 13.1 in 2020, and averaged 4.1 over the period 2009-2021. As this illustrates, the same levers have been relied on for years, leading to a build-up of underlying risks.

Real estate crisis textbook case of underlying risks

The financial stability risks stemming from overleverage in the Chinese economy can be clearly illustrated by the liquidity crisis that has captured the real estate sector since 2021. While the crisis itself is relatively recent, the problems herald back to developments over the past twenty-five years as real estate grew to become a major driver of the Chinese economy, eventually accounting for a quarter of total fixed asset investment in 2021.

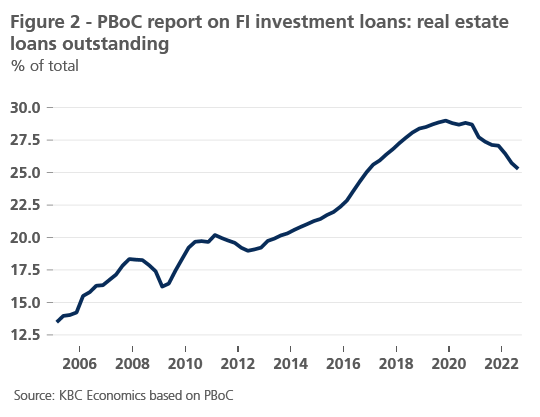

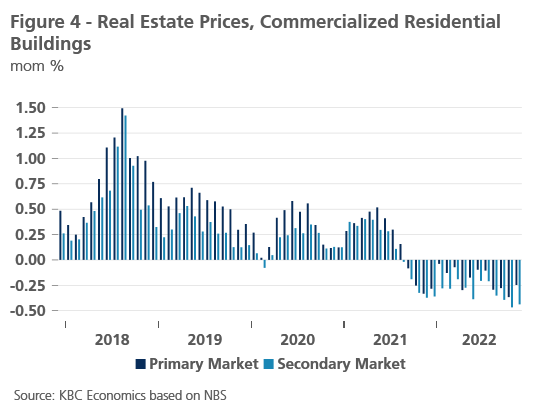

The growing importance of the real estate sector also meant growing debt burdens – not only for households taking out mortgages, but also for property developers – and, hence, potential risks to financial stability. Real estate loans accounted for nearly 30% of financial institutions’ loans outstanding in 2019. That number has since come down (to 25% as of Q3 2022), partially reflecting a policy shift to try and limit overleverage in the sector and, particularly, property developers’ indebtedness (figure 2). A major tenant of this policy shift, known as the Three Red Lines, was introduced in 2020 and placed limits on a property developer’s borrowing capacity based on its outstanding debt relative to assets, equity, and cash. These rules sparked the liquidity crunch among (less creditworthy) property developers and subsequent downturn in real estate prices, but sustainability concerns had already been simmering for some time.

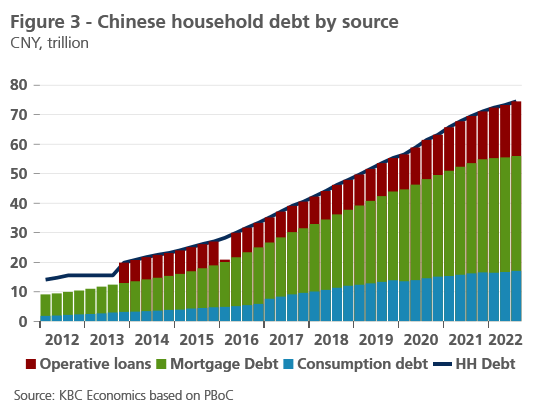

What makes developments in real estate particularly concerning for the larger economy, is that the sector is linked to other sectors in many different and complex ways, making it a systemic risk. First, there is the link with the household sector. As real estate has grown in importance, the housing market has become a major destination for household savings; it is estimated that between 50-75% of household wealth is held in real estate assets1 2. Meanwhile, more than half of the sharp rise in household debt over the past two decades has been driven by mortgage debt (figure 3).

In China, homebuyers often take out mortgages for unfinished homes or apartments. This can function without problem, as long as payments to real estate developers are being channelled toward completing those projects. But as mentioned previously, property developers’ debt has increased substantially over the years, borrowing from both traditional banks and the shadow banking sector alike. The government’s crackdown on shadow banking in recent years, together with the above-mentioned policy to limit property developers’ indebtedness in 2020, induced project developers to increasingly channel the earnings from new projects toward covering debt payments and other costs. This led to stalled projects, which in turn led to some homebuyers stopping their mortgage payments over the summer 2022 (i.e., a mortgage boycott). The problems among property developers have, more generally, shaken confidence in the sector, which is a major reason why real estate prices declined throughout 2022 (figure 4).

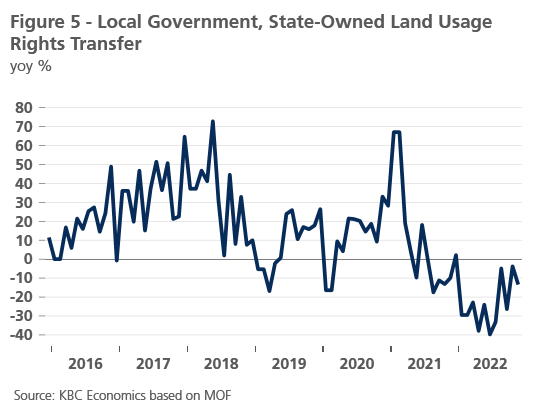

Households are not the only sector exposed to the real estate market. Local governments which are expected to support economic activity and meet growth targets, are also directly affected by the downturn in the property sector. Specifically, one of the main ways that local governments raise non-tax revenues is through land sales (i.e., selling the rights to use state-owned land). Such land rights transfers have been weak since mid-2021, and though there may be signs of some recovery, land sales are still negative in year-over-year terms (figure 5). This is unsurprising given the downturn in the property sector and the inability of some developers to cover debt payments and other costs, let alone buy new land rights.

As land sales and therefore local government revenues have dried up, it has been reported that Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs) are stepping in to buy land from local governments at inflated prices3. LGFVs’ balance sheets are crucial for understanding the financial stability and sustainability of local governments. Since local governments in the past have been limited in the amount of debt they could issue, these LGFVs are often used as a means to finance infrastructure projects and meet growth targets imposed by the central government. These LGFVs are owned by and connected to a local government (leading to assumptions of implicit guarantees and contingent liabilities), but LGFVs are off balance sheet for local governments, and hence LGFV debt is not included in measures of government debt. Rather, they are considered state-owned enterprises and contribute to China’s very high corporate debt ratio. Despite this accounting separation, when LGFVs buy land rights from local governments, the governments are effectively selling to themselves. The central government recognized the danger in this, and in October 2022, the Ministry of Finance introduced a new rule limiting local governments’ ability to inflate land-sale revenue through purchases by linked SOEs. While this rule may help protect against further weakening of the financial stability of LGFVs, it puts further pressure on local government revenues. This means less room for fiscal policy manoeuvring and support at a time when economic growth is struggling to recover.

The central government has since changed track from focusing on real estate deleveraging and is trying to support the sector again; enforcement of the Three Red Lines policy has been eased, the PBoC has reduced mortgage interest rates, and state banks and other lenders have been urged to keep lending to developers. In particular, in August 2022, the PBoC, together with the Finance Ministry greenlighted $29 billion in special loans to be issued to real estate developers (via state banks). These loans should be used specifically to finish stalled projects, thus potentially stabilizing confidence, but not addressing the underlying debt of the developers. Then in November, the government came out with a 16-point plan to rescue the sector, mostly focused on easing the liquidity crisis by encouraging lenders (including banks, trust companies and asset management companies) to support property developers and by extending payment deadlines on developer’s outstanding loans due within the next six months. One major element was the temporary easing of a cap on banks’ property-related lending. The package also included measures to encourage homebuying (e.g., changing down payment requirements and encouraging banks to extend mortgage repayments). While these measures may indeed ease the liquidity crunch and support confidence in the sector, it remains to be seen how authorities will tackle the more structural issue of an overreliance on real estate related growth and the over-indebtedness of the sector.

Financial stability parallels

As mentioned above, the problems in the real estate sector are merely one manifestation of China’s larger debt problem. Indeed, strong parallels can be seen when digging into the financial stability risks of LGFVs. LGFV debt has skyrocketed in recent years, reaching an estimated 39% of GDP in 2020 according to the IMF5. Though there is a lack of transparency surrounding LGFVs, the IMF also estimates that 80-90% of their spending comes from new external financing, mostly in the form of debt. The funding raised by LGFVs is meant to fund infrastructure and other public projects (including real estate development) that help local governments reach local growth targets. But as mentioned previously, overtime such investments have become less and less productive and efficient. This means that earnings from these projects are no longer enough to cover debt repayments, and a significant share of new financing is reportedly being used to cover operating costs.

Extending the parallels to the real estate sector further, it has been reported that LGFVs are finding it increasingly difficult to raise funds6. This may be related to the government’s crackdown on the shadow banking sector and fight against overleverage. As a result, LGFVs are reportedly turning more toward retail investors and paying higher interest rates—a potentially worrisome sign in terms of LGFV liquidity.

It is far too early to say whether LGFVs will run into a similar problem as have overindebted real estate developers. For starters, their balance sheets are opaque, leading to increased uncertainty. In addition, implicit guarantees from the government, for now, support LGFVs’ borrowing capacity. But it is not out of the question that an eventual quest to clean up the debt situation of local governments and LGFVs could lead to a similar liquidity crisis. Such a crisis would almost certainly require intervention from the central government. They do have the capacity to intervene and stem a debt crisis, but not without some pain for the macroeconomic landscape. This is especially true given LGFVs’ important role in funding infrastructure projects that are normally a major driver of economic growth and given their strong connection with the fiscal position of local governments.

III.Finding new engines of growth

The previously mentioned issues are worrisome, but a Chinese debt crisis is, at the current juncture, certainly not inevitable. However, whether simple deleveraging or more substantial reforms of the real estate sector and LGFVs are necessary to address China’s debt problem, either way, China needs to move away from the debt-led growth model it has relied on for many years. Put another way, China needs to find new engines of growth.

Dual circulation agenda

This is where China’s Dual Circulation agenda comes into play. In many ways, dual circulation reflects the long-standing goal of moving China’s export position up the value chain while also expanding domestic demand. There is increasingly, however, an element of self-reliance and even isolation wrapped up in this agenda. Moving up the value chain to higher tech exports means being less reliant on high-tech exports from other countries—a problem that is only intensifying with current China-US relations. Expanding domestic demand and consumption also means less reliance on exports (and investments) as a major driver of growth.

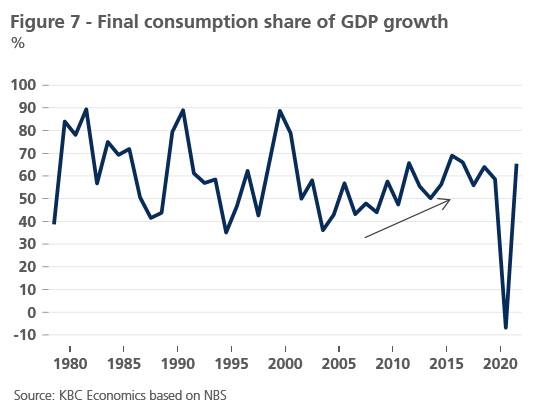

In some sense, we do see progress toward these rebalancing goals. China’s backward participation in global value chains (the foreign value added imbedded in China’s gross exports) has declined over time, while China’s forward participation (China’s own value added in foreign exports) has increased (figure 6). At the same time, between 2005 and the years leading up to the pandemic, the share of final consumption in China’s GDP growth clearly increased (figure 7). However, this increased share for consumption is not all it seems. Over this same period, GDP growth decelerated, meaning higher consumption relative to GDP reflects a higher share of a declining whole, mostly due to investments’ contribution declining rather than consumption significantly increasing. Meanwhile, there are several factors likely to weigh on consumption growth going forward, including high household debt, inequality, and demographics.

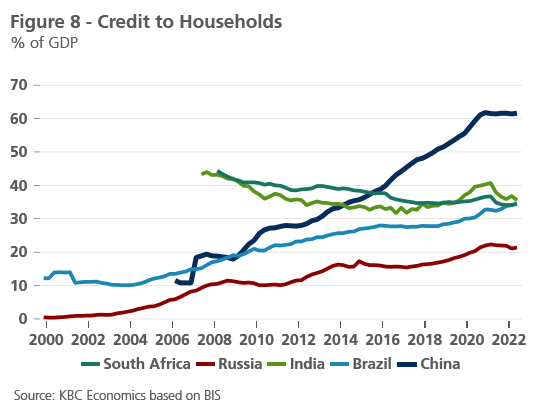

As seen in figure 8, Chinese household debt has sky-rocketed in recent years and, at 61% of GDP, is well above that of other emerging markets or large middle-income economies and is more on par with advanced economies like the euro area and Japan. Such an elevated household debt ratio potentially constitutes an economic vulnerability, as households may focus on balance sheet repair in case of shocks. Some research suggests that household debt above 60% and 80% of GDP has negative effects on consumption and growth, respectively7. Furthermore, with more than half this debt accumulation driven by mortgages and a substantial amount of Chinese wealth tied up in real estate assets, the downturn in the real estate sector is hurting household balance sheets and confidence, and weighing on consumption (for further details see: China's household debt problem (kbc.com))

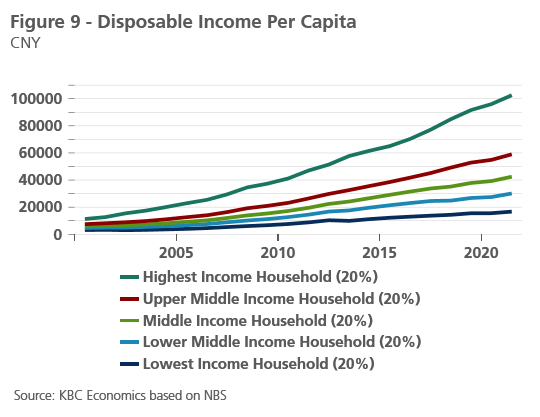

Meanwhile, widening income (and wealth) inequality within China over the past two decades (figure 9), is also linked with higher savings and reduced consumption. This is exasperated by demographic trends and projections for China as well, with China’s population expected to continue aging (and at a faster rate than many G20 nations) in the coming years. This not only means that, all else equal, labour productivity must continue to increase to maintain economic growth. This aging trend, together with widening inequality, and an insufficient social safety net, also encourages savings. Indeed, China’s household saving’s rate is still very high globally, and well above that of high-income economies. Hence, social and economic reforms are clearly still needed to achieve a structural rebalancing of the economy toward a consumption-driven growth model (for further details see: : China's tipping point (kbc.com)).

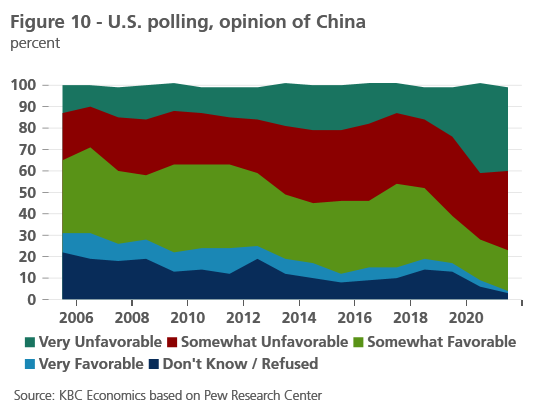

The self-reliance aspect of the dual circulation agenda becomes increasingly important in light of potential decoupling with the US (or the West more generally). Decoupling can refer to many facets of the US-China economic relationship, from goods trade to financial links to technological ties. But a deteriorating geopolitical relationship and a worsening perception of China in the US (figure 10) threatens these links on all fronts.

However, the technological conflict simmers beneath the surface of both trade and financial conflicts and has been heating up recently. China still remains reliant on high tech imports (like semiconductors), especially from Taiwan and elsewhere (including the US). This becomes a point of worry for China given rising geopolitical tensions with Taiwan and the US. The US recently passed the CHIPS act to secure its own domestic supply of chips, but also went a step further a few months ago, imposing restrictions on the export of advanced chips made with US equipment to China. The ban extends to equipment and software for manufacturing chips, and even the ability of US citizens and residents to work for Chinese chip manufacturers. Given the extended use of US equipment for manufacturing chips globally, the policy is a significant measure in terms of isolating and limiting China’s technological progress. But while policy has been framed as one protecting US national security and foreign policy interests, it also applies to dual use chips, meaning those involved in civilian high-tech goods. Hence, the escalation of tensions with the US could mean a major setback for China’s manufacturing sector more generally. This is why technological self-sufficiency remains a major pillar of China’s current economic agenda.

Of course, while China may want to insulate itself from external influence and promote self-sufficiency, true decoupling is tricky and complicated and would result in significant economic losses on both sides. Indeed, a true decoupling can harm China’s growth prospects and casts uncertainty on China’s economic relationships with other economies.

But so far, indications of decoupling from a trade and financial perspective remain limited. On the trade side, there are the lingering effects of the Trump trade war, including tariffs that remain in place. However, trade links between the two economies remain robust for now, dipping after tariffs were first introduced in 2018, but recovering strongly through the pandemic (figure 11). US direct investment in China has not seen significant disruptions either (figure 12). This likely reflects that despite political developments between the countries, the economies are still very interconnected, and decoupling is costly. In light of the escalation of the technology war in recent months, however, the risk of further deterioration of the trade and financial relationship between the two countries has increased.

IV.Conclusion

The challenges outlined above have important implications for China’s macroeconomic outlook in the coming years. Furthermore, they come at a time when China’s economy has already been struggling with a number of shorter-term headwinds that led to growth well below potential in 2022. Though the strict zero-covid policies that were a major contributor to this subpar growth have been lifted, and China is now dealing with an extremely disruptive exit wave, the eventual normalisation of the covid situation in China (perhaps by spring 2023), does not necessarily mean the economic path going forward will be all smooth sailing. China still needs to contend with the legacy of an inefficient build up of debt in recent years and find new engines of growth, all while facing an aging population and a more hostile external environment.

1 Li, Cheng. 2017. “China’s Household Balance Sheet: Accounting Issues, Wealth Accumulation, and Risk Diagnosis.” Munich Personal RePEc Archive No 79838.

2 Xie, Yu and Yongai Jin. 2015. “Household Wealth in China.” Chinese Sociological Review, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 203-229, doi: 10.1080/21620555.2015.1032158.

3 China’s local government financing vehicles go on land-buying spree | Financial Times (ft.com)

4 China’s 16-Point Plan to Rescue Its Ailing Property Sector - BNN Bloomberg

5 Hoyle & Jeasakul. 2021. “Local Government Financing Vehicles Revisited.” IMF Country Report No. 22/22: People’s Republic of China, Selected Issues.

6 China’s growth hopes rest on troubled local government financing vehicles | Financial Times (ft.com)

7 Lombardi, Marco, Madhusudan Mohanty, and Ilhyock Shim. 2017. “The real effects of household debt in the short and long run.” BIS Working Papers No 607.