China and Hong Kong’s important relationship

China’s unique economic model appears to reconcile a number of seeming contradictions. It is moving towards a market economy but still relies on centralized planning and industry protections. It hopes to boost lending to small private companies rather than rely on state-owned-enterprises but does so by leaning on large, state-owned banks. And as its importance in global markets grows, it is reaping the benefits of a more open financial system while still maintaining capital controls and investor restrictions. This last apparent contradiction has become more notable in light of the current protests in Hong Kong. Hong Kong, as a prominent global financial hub with its own governance system, has allowed China to dip its toes into global financial markets while keeping its own financial sector “dry” and under government control. But part of what makes Hong Kong a financial hotspot is its independent rule of law. China wants the best of both worlds, but to get that something may have to give. Whether with Hong Kong, or through other cities, if China wants to continue its entry into the global financial system, it will likely either have to step up its financial market liberalisation or ensure Hong Kong’s unique status in relation to the mainland.

An international powerhouse…

China’s economy is in transition. The government is focused on increasing the value-added in the country’s manufacturing and export sectors (i.e. higher tech exports) and on driving economic growth through domestic demand and services. China is also trying to move from a middle-income country to a high-income country and to expand its international influence, e.g. through the Belt and Road Initiative. As the second largest economy in the world, and with a GNI per capita that has more than tripled in the past 10 years, it is well on its way to achieving these goals. But challenges remain, especially given China’s substantially large debt burden, both among corporates and households (see KBC Research Report from May 2019).

…with a still closed financial system

One area where there is still significant progress to be made is in the opening up of China’s financial system. Restrictions on international investors trying to invest or open businesses in China have been a major complaint of both the US and the EU. It is not a coincidence that under pressure from the trade war, China announced a timeline to remove restrictions on foreign ownership of futures, mutual funds, and securities companies throughout 2020. But while China has introduced limited opening up measures, China is far away from full capital account liberalisation. According to a June 2019 report from Merics, a German think tank focused on China, capital controls currently in place include, inter alia, restrictions on cross-border transactions, reporting obligations for banks on daily transactions above CNY 50,000 (USD 7,000), facial recognition at Macao ATMs to withdraw cash, restrictions on cash withdrawals overseas, and restrictions against “irrational” overseas investments. Thus, with every step towards more openness, China has kept one hand on the faucets. It has imposed safeguards to prevent the possibility of volatile capital outflows often associated with open markets.

This slow move towards more open capital markets is a prime example of China’s unique economic model. On the one hand, increased openness is important for China’s goals of moving up the value-chain ladder and increasing the country’s influence abroad. The former requires inward investment, especially in light of China’s shrinking current account surplus and growing fiscal deficit, while the latter is being driven by outward investment in other countries. On the other hand, strict control over the financial system, and therefore interest rates and the exchange rate, is an important facet of a centrally planned economy. It has helped promote financial stability in China despite slowing growth, growing debt burdens, and increasing complexity in lending.

Hong Kong’s special role

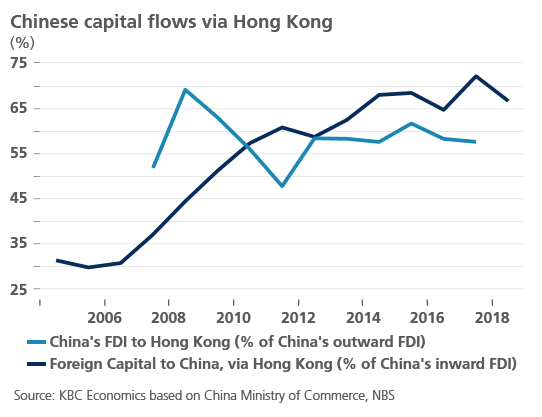

So how has China managed to selectively open its financial system? Much of the answer lies with Hong Kong. When Hong Kong was returned to China in 1997, separate legal and judicial systems were established for the Special Administrative Region until 2047. This allowed Hong Kong to maintain the legal framework and institutions that had contributed to it becoming a leading financial centre. Indeed, international investors’ preferences for transparency and market friendly institutions have made Hong Kong a gateway from the rest of the world to China. Over 65% of foreign direct investment into China, for example, is channelled through Hong Kong. The reverse is also true, with much of China’s outward investment flowing first through Hong Kong (figure 1). A large share of Chinese companies’ Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) and bond issuances happen in Hong Kong, and Bond Connect and Stock Connect are schemes that allow for (controlled) equity and bond trading between mainland China and the rest of the world. Thus, so far, China has had the best of both worlds. It has access to international markets via Hong Kong while still maintaining tight control over the capital flowing in and out of its borders.

A reputation under pressure

As noted in the KBC Economic Perspectives of November 2019, the events in Hong Kong are a clear drag on Hong Kong’s economy. But they can also be damaging from a long-term, structural perspective. Questions surrounding Hong Kong’s status are not going away. As 2047 edges closer, there are reasonable questions about whether Hong Kong’s independent legal system and the rule of law will disappear. If these important facets of Hong Kong’s institutional set up do slip away, the comparative advantage that Hong Kong has as a financial hub compared to say, Shanghai, diminishes. But that comparative advantage is still important to China because the inflow and outflow of investment, subject to government control, is crucial to China achieving its many goals as an international superpower. The recent passage of US legislation that puts Hong Kong’s special economic status with the US under tighter scrutiny highlights how China and Hong Kong’s unique economic model could be in jeopardy. Thus, it seems China currently has three choices: either guarantee Hong Kong’s separate status beyond 2047, speed up the country’s financial market liberalization (accepting the consequences that such openness might have for financial stability), or accept that the transition to a high-income, high-tech, global economy, may take longer than previously expected.