Bank credit supports the economy

While the European banking sector was part of the economic problems in the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the euro crisis of 2011, it is now part of the solution. In particular, companies have significantly increased borrowing from banks in recent months, which has strengthened their liquidity buffers. Thus, during the coronavirus shock, the banking sector has done its bit to stabilise the economy. The role of the banking sector also remains important for the post-pandemic economic recovery. The sector is facing a difficult search for the right balance between a credit policy that is not too strict and a credit policy that is not too flexible. This balancing act is not new. It is at the heart of the banking profession. But the coronavirus shock is a real game changer, which can also bring down previously healthy companies. That makes the balancing exercise extremely difficult. The biggest pitfall is that so-called ‘zombie companies’ are kept alive too long. That would allow the economic malaise to drag on and affect the longer-term growth potential of the economy. This must be avoided, even if it sometimes requires unpopular decisions in difficult circumstances.

Surging credit growth...

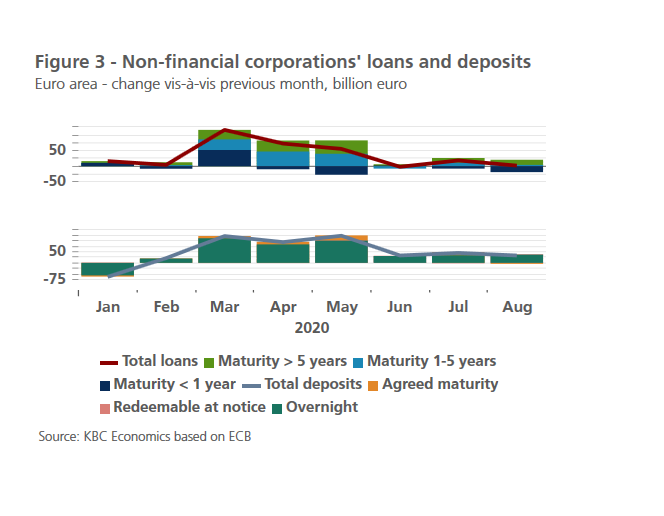

The unprecedented economic downturn in the first half of 2020 was accompanied by a remarkable acceleration in bank lending to non-financial corporates (NFC). In the euro area, NFC credit growth rebounded from 3% (compared to the previous year) in early 2020 to 7.3% in May. This is the highest level since the beginning of 2009 (Figure 1). In June-August it stabilised at around 7.1%. Household credit growth decelerated slightly as consumer credit growth came to a standstill during the lockdowns and barely recovered afterwards. The growth rate of housing loans, which represents a much larger proportion of loans to households, has remained more or less stable at just over 4% since the onset of the coronavirus crisis.

The upturn in bank loans to businesses contrasts with developments during previous crises. When the US banking crisis blew over to Europe in 2008, the flow of credit to companies in the euro area came to a standstill. The euro crisis of 2011 was even followed by several years of shrinking credit. While the banking sector was then part of the economic problem, it is now contributing to the solution.

... stabilises the economy

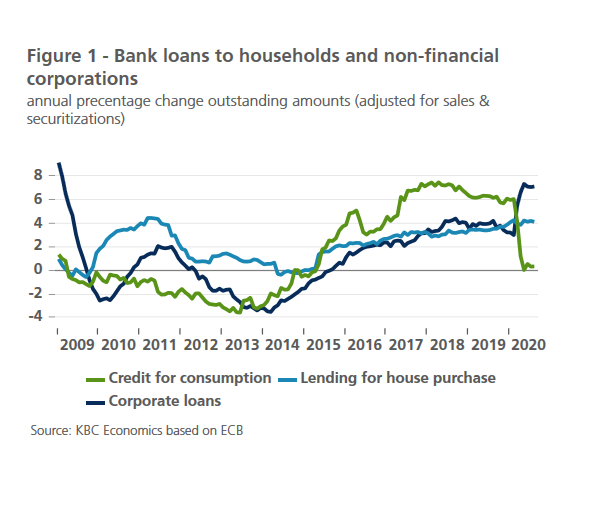

Indeed, the expansion of bank credit was an essential part of the stabilisation of the economy during the lockdown. As could be expected during a recession, demand for investment credit plummeted. However, the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey shows that corporate demand for credit for stock financing and working capital reached an unprecedented peak in the second quarter (figure 2).

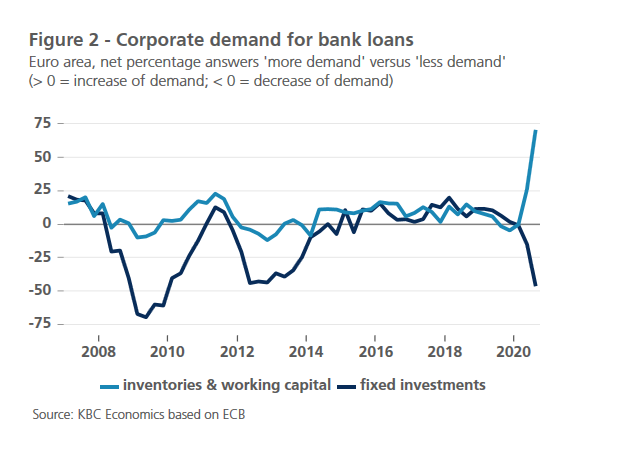

Companies used the borrowing to strengthen their liquidity buffers during the lockdown in March-May. Figure 3 illustrates the parallel course of credit take-up and deposit growth. Companies took up credit and parked it in their current account. In this way they strengthened their liquidity buffer. The further slight increase in corporate deposits at the banks during the summer months suggests that they did not have to draw on these buffers en masse. Moreover, the easing of lockdowns from May onwards allowed them to convert (on balance) short-term loans (< 1 year) into medium (1 - 5 years) and long-term loans (> 5 years). This may indicate a relatively strong resilience of the business sector as a whole, which also allowed it to increase its financial resilience. This would be encouraging for the economic recovery.

Delicate balancing exercise

Bank lending remains very important for that recovery. Banks are facing an extremely delicate balancing exercise. Too strict a credit policy increases the chances of business failure and unemployment. This would exacerbate the economic malaise and, by increasing credit losses, also harm the banks themselves. Excessive leniency would, however, put the banking sector at excessive risk. This threatens to exacerbate the economic damage in the long term. In addition, companies that are not viable today or in the future and do not have sufficient financial buffers of their own (so-called ‘zombie companies’) would prolong an economic crisis and erode the growth potential of the whole economy, as scarce resources remain immobilised in a unproductive way. This pitfall must be avoided. In the worst case, the banking sector itself gets into trouble.

The balancing exercise is, of course, nothing new for banks. Dealing with it is a core competence of the banking métier. Nevertheless, the uncertainty caused by the pandemic makes the exercise even more difficult today. Banks that invest in long-term relationships with their customers and know their customers well may find it easier to successfully manage this exercise. But for them, too, the challenge remains exceptional. There is a growing awareness that the coronavirus is a real game changer, which can also bring down previously healthy companies. A sharp nose for early ‘zombie’ detection is therefore more important than ever. And it will sometimes require unpopular but necessary decisions in a difficult environment.