A US withdrawal from NAFTA would not be a wise decision

Already before President Trump was elected, he expressed his discontent about the current form of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between the US, Canada and Mexico. Consequently, renegotiation rounds started quickly. The general mood in these negotiations has recently deteriorated and concerns about the US withdrawing from NAFTA have become more legitimate. Leaving the trade deal would however be the wrong decision for the US economy. After all, although the consequences of NAFTA were not all roses, the benefits of the trade deal have been felt economy-wide. Furthermore, Mexico in particular would have ample room to retaliate against the US in the context of a hostile trade relationship.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Canada, Mexico and the US entered into force in 1994. The deal heralded a period of increasing trade and financial flows between the three countries. The current US administration’s support for NAFTA is however rather limited. Already during his election campaign, Trump signalled his discontent about NAFTA saying it was “the worst trade deal maybe ever signed anywhere, but certainly ever signed in the US”. Trump usually mentions job losses caused by NAFTA - with some estimates pointing at 600,000 job displacements - as the main argument for this provocative statement. Not unexpectedly, the first round to renegotiate the terms of the deal already took place in August of this year. Although Trump’s rhetoric around NAFTA was at times hostile and arguably always appropriate, the essence of it – namely to adjust the details of the 23-year old deal – is far less controversial. Since the agreement was signed, the global economy has changed a lot. For example, the sector of e-commerce didn’t even exist at that time. Hence, a modernisation of the agreement doesn’t seem so odd. However, the US negotiation team wants to go much further than a mere upgrade. Instead, they aim for a “fair” trade deal that brings back jobs and decreases the large US trade deficit. The White House website even states that if negotiation partners refuse such a renegotiation, the President will give notice of the US intent to withdraw from NAFTA.

The latter has become more probable recently. Today, the fifth negotiation round begins. Although the atmosphere at previous rounds was relatively constructive, the fourth round was characterised by little common ground. The main reason was a hardening in the US stance with proposals that were unacceptable to the Mexican and Canadian governments. As a result of these tensions, negotiations will be extended into 2018. It may be that the unreasonable demands by the US are just a negotiating tactic. However, one could also interpret it as a way to provoke Mexico and Canada to leave the table, so that they look responsible for the failure of the negotiations. Though in our view, sabotaging negotiations so that NAFTA is abolished, would not be one of President Trump’s wisest decisions. After all, also the US economy would be worse off without NAFTA.

As mentioned above, the consequences of NAFTA have not been all roses. Besides the job displacements mainly concentrated in the auto industry, the US trade deficit with Mexico has increased sharply since the start of NAFTA. However, this does not mean that the end of NAFTA will reverse these trends. After all, bringing lost jobs back to the US is not as evident as Trump claims it to be. Besides, a number of studies state that some of the negative economic effects even might have occurred without NAFTA. Moreover, the negative impact was highly concentrated in specific sectors, while the benefits of the agreement are economy-wide. Larger export shares, efficiency gains and lower prices are beneficial to all Americans. Note that, a US withdrawal from the trade deal doesn’t mean that trade flows will immediately collapse to zero and all positive effects will be instantly offset.

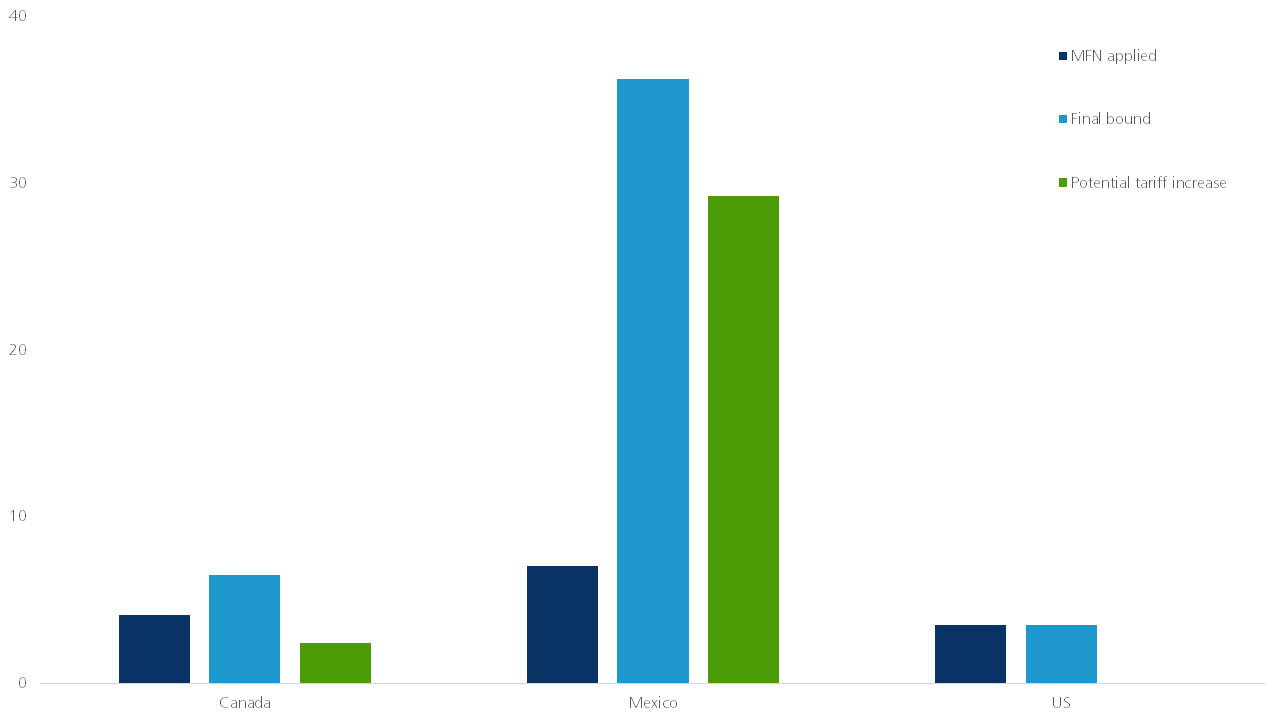

Figure 1 - Tariff rates under WTO rules (simple averages; 2016; in %)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on WTO Tariff profiles (2017)

There are nevertheless additional unfavourable effects of a withdrawal from NAFTA. Most likely, the direct impact of a unilateral withdrawal would be a substantial depreciation of the Mexican peso and Canadian dollar against the American dollar. This would adversely affect US exporters. Furthermore, the uncertainty over the potential new trade framework might weigh heavily on US output and domestic and foreign investments. Also and in particular in the longer-term, withdrawing from NAFTA will not be in the US economy’s interest. Trade would revert to most-favoured-nation (MFN) rules from the World Trade Organisation (WTO). These MFN tariffs are what WTO members impose on imports from other WTO members with which they do not have a preferential trade agreement. Hence, as Canada and the US had already agreed upon a FTA before NAFTA, the former would likely only apply to trade with Mexico. The average MFN tariff level in the US is 3.5% while in Mexico it stands at 7% (figure 1). Therefore, US exporters shipping products to Mexico would face a higher increase in tariffs than Mexican firms exporting to the US. The average tariff level would be rather contained, but the large differences across goods would raise trade costs for certain products sharply (e.g. agricultural goods).

Furthermore, in the context of a hostile trade relationship, retaliation is likely and hence bound tariff levels are important to take into consideration. These bound rates are the maximum tariff level that a country can apply without violating WTO rules. The average bound rate for the US is roughly equal to its MFN rate. Hence, if the US doesn’t want to violate WTO rules, it can hardly increase its tariffs. In contrast, the average bound rate for Mexico is much higher than its MFN rate and equals more than 36%. The potential tariff increases that US exporters face in Mexico, might hence be very high (figure 1). According to WTO rules, if Mexico chooses to increase its tariffs towards the bound rates, it would be obliged to charge that tariff to all of its trade partners with which it does not have trade agreements. However, since Mexico is part of nineteen trade deals, a large part of its imports are without duties. This means that Mexico could easily raise tariffs on those products that it can import from its trade agreement partners to retaliate against the US. Certain American industries are particularly vulnerable to such Mexican tariff hikes. One example is the steel sector for which the Mexican bound rate is 35%. A tariff increase of this amount would hit American steel producers hard as Mexico could still import steel from elsewhere without higher trade costs. In sum, if NAFTA came to an end, Mexico would have ample room to retaliate against some US sectors. In that case the US would have no similar defence measures, although it might still use other trade defence measures (e.g. anti-dumping measures).

As said earlier, the tougher US demands could just be a tactical move to increase pressure on Mexico and Canada. A US withdrawal from NAFTA is therefore not certain yet. If President Trump does decide to pull out of the trade agreement anyway, it might signal a more extreme protectionist stance towards all international trade. This tendency would not only harm the US, but would also be detrimental to the global economy as a whole.