Putin 4.0: Is this time going to be different?

Vladimir Putin was elected President of the Russian Federation for the fourth time in March. As a welcome gift, he received a package of fresh sanctions from US President Trump targeting major Russian oligarchs and their companies. This will undermine his ambitious plan to reform the Russian economy introduced in his inaugural speech. Even without the sanctions, however, previous experience does not suggest that the Russian economy is to experience significant transformation. Therefore, the Russian economy will most likely remain heavily dependent on its commodity industries, i.e. an economic model that is associated with persistent institutional weaknesses.

Yesterday, the World Cup kicked off in Russia, which will attract more than 3 billion viewers over the next month. However, the ambitions of the home football team are very modest. However, when it comes to the economic ambition, it is a completely different story. According to the inaugural speech of President Vladimir Putin, Russia is to become one of the world’s five largest economies in the next six years.

Ambitious goals, but obstacles remain

Vladimir Putin was elected for the fourth time in March as Russian President. Rather than a growing standard of living, agitation and a number of more or less unrealistic promises were behind this success. The Russian economy is still struggling with the effects of the economic recession of 2015-16 caused by the collapse of oil prices (from 115 USD per barrel in June 2014 to below 30 USD per barrel in January 2016), and amplified by Western sanctions in reaction to the annexation of Crimea. The sluggish real GDP growth of 1.5% last year only underlines the prevailing problems that call into question the achievement of the so-called national development goals by 2024. In addition to catapulting Russia from the twelfth position into the top five of the world’s largest economies (before the UK, South Korea or India), these goals also include reducing the poverty level by half, ensuring sustained natural population growth and significant productivity growth and technological innovation.

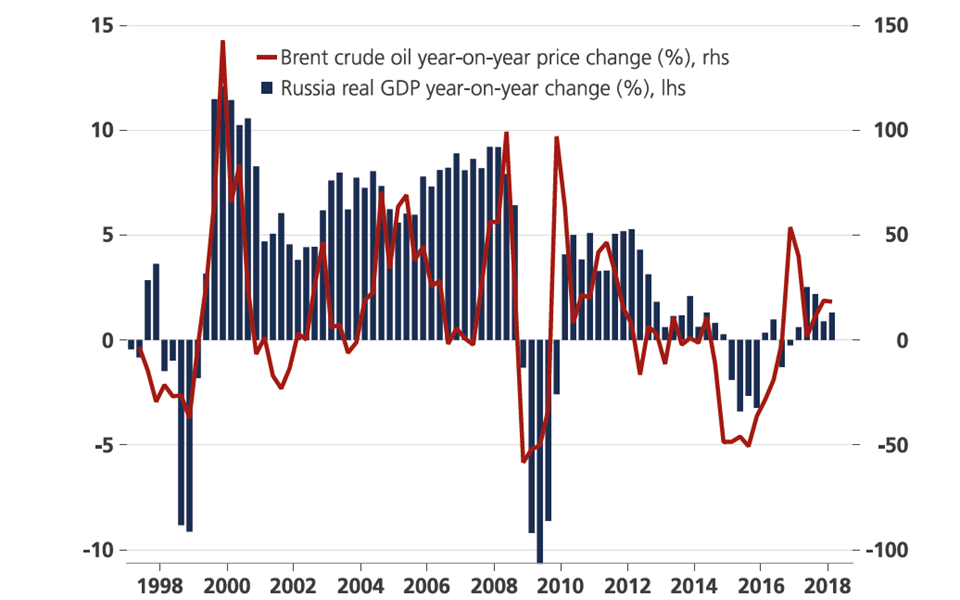

The fundamental problem of meeting these goals is that they require a drastic transformation of the Russian economic model. This is primarily based on the country’s vast natural resources, predominantly oil and gas (Figure 1). They together account for more than a third of the government budget revenues and even more than half of export revenues. In addition, this model carries long-term institutional weaknesses, i.e. the increasing share of the state in the economy (around 70 %), widespread corruption and weak innovation capacity. In the medium to long-term, Russia will also have to deal with the effects of adverse demographics, which the government has yet failed to address.

Figure 1 - Russian economy remains highly dependent on oil price

Moreover, Russia has to live with the economic sanctions from the West as a result of its expansionist ambitions. Annexation of Crimea prompted the US and the European Union to respond by comprehensive sanctions that have restricted Russian entities’ access to foreign financial markets as well as foreign technology in the energy and arms sectors. A new round of sanctions imposed by the US in April this year, responding to the alleged Russian interference with US domestic affairs, further deepened the sanctions regime. For the first time, sanctions were targeted not only at individuals but also at companies controlled by these individuals, which was particularly troublesome for the aluminium market as Russian aluminium giant Rusal (responsible for 6% of global production) was sanctioned. Furthermore, the risk of further tightening sanctions may cause uncertainty and weigh on confidence. In the long term, the restriction to access the Western technology seems to be the most problematic aspect, further undermining the country’s innovation potential.

2018 is not 2014

On the other hand, compared to 2014, Russia is in a more comfortable position. Firstly, Russia’s external position is stronger, which makes the economy one of the least vulnerable among emerging markets. The current account is in sufficient surplus (Figure 2), foreign exchange reserves are rising, the government debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively modest and the share of volatile foreign short-term debt is declining. Moreover, Russia has managed to improve its macroeconomic framework, i.e. let the rouble float freely, implemented the inflation targeting regime, and introduced the counter-cyclical fiscal rule, which requires the excess revenues from oil compared to the budget (with a conservative 40 USD per barrel benchmark) to be saved in the National Welfare Fund.

Figure 2 - Current account surplus in healthy surplus (in % of GDP)

Rising oil prices, however, are the most fundamental difference compared to 2014. They explain why the new round of sanctions have not triggered a similar disruptive storm as in 2014. In this respect, Russia has benefited from cooperation under the OPEC+ (14 OPEC and 10 Non-OPEC member states) scheme, which since the beginning of 2017 has been collectively curbing production by 1.8 million barrels per day, about 2% of global oil production. As a result, the price of oil had temporarily risen up to 80 USD per barrel recently, more than 70% since the agreement was in place. Although Russia is now pushing for a gradual ease of production limits, some form of cooperation with the cartel will most likely persist. For Russia, this cooperation has not only been successful in increasing oil prices, but also in terms of strengthening its international position by playing a key role in this arrangement.

More of the same

Nevertheless, the successful cooperation within the OPEC+ illustrates the continued excessive dependence of the Russian economy on oil. President Putin’s plans are not new, but, as in the past, specific steps how to reach these goals are missing. In addition, the current situation is less favourable for far-reaching economic reforms than was the case when the oil price was well above 100 USD per barrel. What outcome, then, to expect for the Russian economy after (possibly) the last six-year term of Vladimir Putin in power? Simply put: more of the same…