Income inequality contributes to lower real interest rates

In recent decades, the ‘natural’ interest rate (r*), which balances planned savings and investment, has been on a downward trend worldwide. Among other things, this has had serious consequences for monetary policy. The consensus among economists is that the downward trend is mainly the result of developments in the determinants of macroeconomic saving and investment. Income inequality is one of them. After all, to the extent that the trend of inequality increases and higher income percentiles have higher savings ratios, a lower r* is needed to restore the balance between savings and investment. This is supported by both theoretical and empirical literature. In addition, research by economists at the Bank for International Settlements suggests that the very low r* may also be determined by other factors, such as the persistence of highly accommodative monetary policy. Under this hypothesis, central banks are not only affected by the low r*, but they are also partly causing it. If this hypothesis is correct, it is high time for a policy reversal.

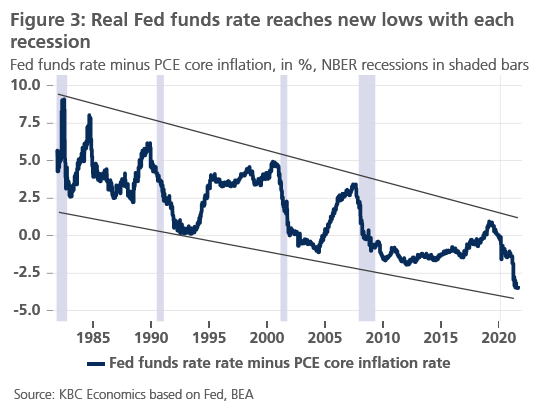

During the past decades, the ‘natural’ rate of interest (r*) has shown a declining trend (Figure 1). R* is the real (inflation-adjusted) short-term interest rate that balances planned macroeconomic saving and investment (including the balance of the public budget and of the current account) under conditions of full employment and stable inflation. This interest rate concept provides an important benchmark for monetary policy makers. A real policy interest rate higher than the natural rate has a restrictive effect, while a lower real policy interest rate has a stimulative effect.

However, the natural rate of interest is a rather abstract concept. Fed board member Warsh called it a variable that in practice is unobservable, unpredictable, imprecise, and highly volatile (Warsh (2018)). Nevertheless, r* is often referred to in monetary policy debates. A low r* is said to limit the scope for central banks to stimulate the economy through their real policy rates if necessary. The low r* thus becomes an important justification for non-conventional policies in the form of financial asset purchase programmes by central banks.

What drives the natural rate ?

Since the natural interest rate provides a balance between planned macroeconomic saving and investment, the literature traditionally also refers to saving and investment determinants to explain the declining trend of the natural interest rate (e.g. Lane (2019), Brand et al. (2018)). In a nutshell, the main factors are related to the declining trend in potential growth, which in turn has to do with, among other things, weaker growth in total factor productivity, a larger share of the service sector experiencing slower productivity increases, and the declining growth of the working-age population. All these factors lead to slower growth in investment demand and thus, ceteris paribus, to lower natural interest rates. On the savings side of the equation, demographic developments, in particular rising life expectancy, may also lead to more precautionary savings, putting further downward pressure on the natural interest rate.

Income inequality

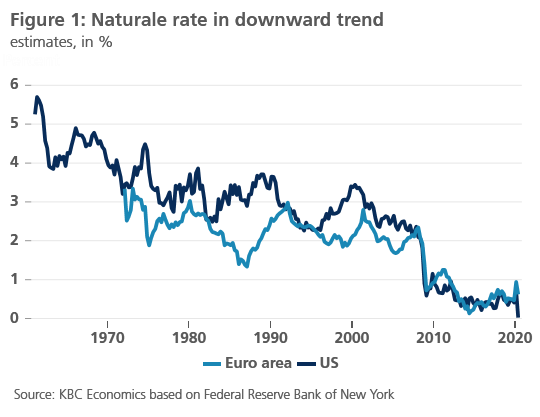

Increased income inequality in many large economies (Figure 2) is also often referred to as a driver of increased saving, and thus of the lower r*. To the extent that higher income categories have structurally higher saving rates than lower ones, the trend of increasing income inequality leads to an increasing trend of net saving in the economy and consequently, ceteris paribus, to a decline of r* (Mian (2021), Lane (2019)).

Econometric research by economists at the Bank for International Settlements supports this hypothesis (Borio et al. (2017) and Rungcharoenkitkul (2020)). They find a significant (bivariate) relationship between increasing income inequality and a lower natural interest rate. When they simultaneously take into account the other traditional savings-investment determinants of r*, the link is still there, but it is not statistically significant for each sub-period considered. This may be due to the smaller number of observations.

Monetary regime

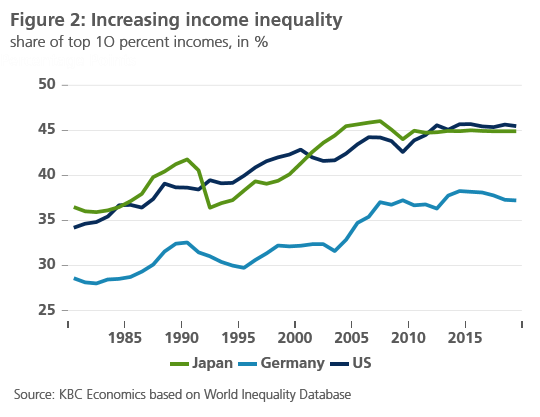

Structural changes in the monetary regime also appear to play a role in this analysis. This allows the hypothesis that monetary policy is not only affected by the downward trend of r* but is at least partly responsible for it. Figure 3 suggests that the increasingly accommodative monetary policy in the US has indeed led to anomalies. For example, the Fed’s real policy rate has had to go deeper and deeper with every recession in recent decades to provide the desired degree of economic and financial stabilisation (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 29 November 2019).

If monetary policy really contributes to an ever lower r* itself, it is high time for a policy reversal (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 8 May, 2019). Via a higher r*, that reversal would again create policy space for the conventional interest rate channel in future recessions.