Fiscal policy: forgotten tool in inflation battle

Fiscal policy in many euro area countries faces clashing choices between, on the one hand, calls for more public money for numerous social needs and, on the other, the need to save for the sake of public finance sustainability. That choice should not blind policymakers to the role of fiscal policy in fighting inflation. A recent IMF study shows that limiting public spending could help reduce inflation in the euro area, and somewhat reduce the need for interest rate hikes by the ECB. Since inflation is a currency union-wide problem, tightening fiscal policy in all euro area countries, regardless of their debt levels, would make the biggest contribution. This requires coordination, which would probably work better with a stronger fiscal capacity at the currency union level.

Blinded by ripping choices

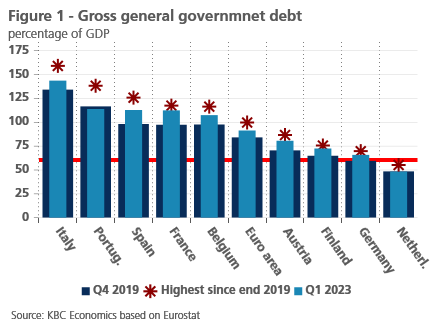

Fiscal policy faces clashing choices. On the one hand, needs for additional spending pop up on all sides: ageing, greening the economy, digital transition, strengthening defence, education, health care, and so on. On the other hand, the sustainability of public debt calls for thrift. After all, support measures during the covid and energy crises sent public debt ratios soaring everywhere, although the post-pandemic growth recovery and especially high inflation have already caused a (possibly temporary) reversal in the meantime (Figure 1).

Because fiscal policy was, until recently, flanked by expansionary monetary policy, with the European Central Bank (ECB) keeping interest rates extremely low and largely absorbing the growth in government debt by buying government paper itself on the secondary market, debt sustainability posed no problem. The tight rules of the European fiscal framework were rendered unproblematic by activation of the so-called escape clause in 2020-2023. The policy focus was on filling emerging needs.

However, the fiscal rules will come back into force in 2024, and the inflation surge has meanwhile made the ECB change its policy. It is no longer a (net) buyer of government securities and has raised its policy rate to the highest level since the start of the currency union in 1999. Long-term interest rates have also risen and interest charges in government budgets are gradually starting to rise again after years of decline. We may not be (now or in the future) at this point, but with ailing economic growth, rising interest rates are reviving prospects of a doomsday interest and debt snowball in public finances, especially as the ECB is far from winning its battle against inflation. It remains an open question how high it will have to raise interest rates to nip inflation in the bud.

Avoiding policy conflict

In this context, it is sometimes feared that high public debt would restrict the ECB’s room for manoeuvre. Indeed, by raising interest rates too much, it would itself jeopardise the sustainability of public finances, at least in highly indebted countries. These fears are understandable, as countries with debt ratios above 100% of GDP account for about half of the euro area’s GDP. If they fall into a debt crisis, it affects the entire euro area.

But such fears remain blind to the fact that responsibility for the sustainability of public finances lies primarily with the fiscal authority and that fiscal policy also affects inflation. A central bank can fight inflation by raising interest rates and reducing liquidity, but that only reduces inflation if it cools demand. Meanwhile, if fiscal policy continues to support (or, a fortiori, stimulate) demand, that works against monetary policy. In contrast, a fiscal authority can facilitate the central bank’s inflation battle by curbing (consumer) government spending, thereby helping to slow demand. Falling demand can lower inflationary pressures. It limits firms’ pricing power and can spur price competition.

Recent research by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds that a reduction in government consumption in all euro area countries by one percentage point of GDP in 2023 and 2024, followed by a reduction of half a percentage point in 2025 would allow the ECB to keep policy rates 30 to 50 basis points lower in the period 2023-2025 than in a baseline scenario. The peak of the policy rate in the second year could be 30 to 70 basis points lower. Still, core inflation would be 0.15 to 0.25 percentage points lower in the first two years. A small negative impact on GDP in the first year would be reversed afterwards. The government debt ratio at the end of 2025 would be two percentage points lower than in the baseline scenario and the risks to financial stability would be smaller.

Phasing out energy support insufficient

The study notes that the simulated savings in current public expenditure can be seen as a rollback of the support measures introduced in 2022-2023. There is a fairly broad consensus on the appropriateness of that rollback. On its urgency, less so. In spring, the European Commission had proposed that member states phase out energy support measures by the end of 2023, but the Council decided to phase out only emergency support, not by the end of 2023, but “as soon as possible in 2023 and 2024”. However, the European Fiscal Board’s opinion on the appropriate fiscal policy for 2024 states that an appropriate fiscal policy should go even further than just phasing out energy support measures partly because a more restrictive fiscal policy would allow lower policy interest rates and reduce the risk of financial instability.

Should countries with high debt make more substantial savings, as the Fiscal Board also advises? It would improve the sustainability of their public finances, especially if it reduced the risk premium on their debt. But the IMF study points out that they would then experience a stronger economic downturn. It also argues that limiting fiscal effort to high-debt countries would result in a smaller drop in inflation in the euro area. For the same inflation reduction, high-debt countries would have to double their effort. Despite its favourable effect on their debt ratio, such a scenario is rather unreasonable, as the economic price for the inflation reduction would fall disproportionately on only some of the countries, while the inflation problem is a euro area wide problem. The scenario would only be realistic if the euro area had instruments to encourage and help highly indebted countries to do so. It leads the IMF to conclude that the currency union needs to be strengthened with fiscal instruments that would allow for better absorption of economic shocks. A conclusion we can wholeheartedly endorse.