The NBP fights a drop in demand, but the economy might say the opposite

The National Bank of Poland surprised markets with an aggressive 75bp rate cut in early September. The NBP's decision for a radical start to monetary easing was based on the argument that the faster-than-expected decline in inflation was due to a negative demand shock that required a swift and decisive response. However, our analysis of the shocks to the Polish economy does not support the hypothesis of an unexpected fall in domestic demand. Therefore, a deep interest rate cut did not make (much) sense in Poland, which was quickly understood by the FX market. It sent a clear signal to the NBP via a weaker zloty that this was not the way to achieve the inflation target. We are therefore not surprised that the NBP has already started to tone down its dovish rhetoric and is now announcing that it will proceed with gradual and cautious easing next time. Moreover, Poland is facing parliamentary elections, and any further policy mistakes could become more visible.

The story about negative demand shocks

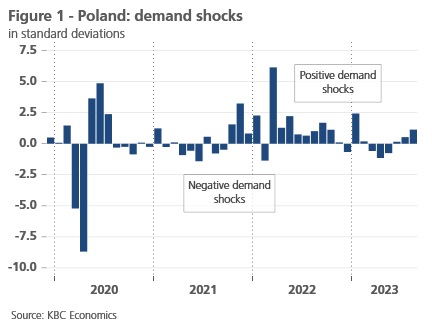

Negative demand shocks in the Polish economy were indeed observed in the spring of this year. The ongoing war in Ukraine and the mediocre performance of German industry appear to be the logical culprits. However, this story did not continue into the summer. Rather, the growth in Polish industrial production last month points to a positive demand shock in August (see figure 1). Admittedly, sentiment indicators are falling, but nowcasts still point to growth of the Polish economy in the third quarter.

Consequences for inflation

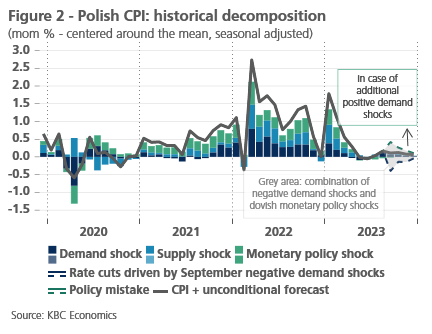

Irrespective of whether the policy rate cut was a catch-up move, i.e. if there was less need to keep interest rates high after negative demand shocks in the spring had already brought inflation down unexpectedly, the persistence of high interest rates over the summer further dampened inflation. In figure 2, we distinguish two scenarios. In the blue scenario, we add negative demand shocks in September which, on average, are followed by an aggressive monetary policy move like the one in September. The monetary policy move mitigates some, but not all, of the downward impact of the negative demand shocks on inflation. In the green scenario, the September rate cut is considered to be a monetary shock, i.e. not a natural response to new demand or supply shocks. In this case, inflation might pick up again. The grey area in figure 2, which lies between the two scenarios, views the interest rate cut as a combination of a natural response to negative demand shocks and positive monetary shocks. For example, the National Bank makes an above-average easing to prevent inflation from falling below its monthly long-term growth rate in the wake of negative demand shocks.

If further negative demand shocks fail to materialise, or even if positive shocks follow, there is a risk that inflation will rise again, more than in the green scenario, which even excludes negative supply shocks due to OPEC+ cutting oil production.

NBP should also watch zloty and election results

However, even ignoring the analysis of economic shocks to the Polish economy, we think the NBP should be more cautious with its easing. First, the major central banks in the core markets, led by the Fed, have not necessarily completed their hiking cycle, and if the NBP goes against this trend, it may put pressure on the zloty (Fed Funds could be above the NBP base rate in November) and thus ease monetary conditions further than would be desirable. Secondly, it should be remembered that Poland has parliamentary elections on 15th October and both the conservative ruling coalition and the liberal opposition are on record as promising a decent fiscal stimulus. While it is by no means certain that the post-election fiscal expansion will materialise, for the NBP, the elections may represent an additional uncertainty of another positive demand shock - this time from the fiscal side.