China’s lockdowns add to supply chain woes

Content table:

- Introduction

- Signs of pressure

- Global implications

- Demand side considerations

- A quantitative view

- Conclusion

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Introduction

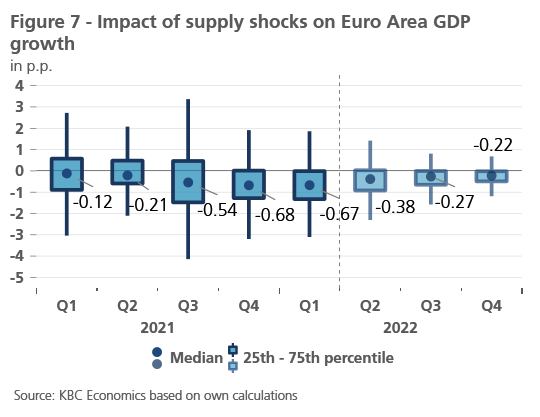

The supply chain troubles that have plagued the global economy since the onset of the pandemic are yet to unwind. There are many factors that have contributed to the recent period of disrupted production (and distribution) networks, including the initial logistic challenges posed by the lockdowns and reopening of economies in early 2020, intermittent and more local covid restrictions that have added to congestion at major ports over the past two years, a sustained demand shift from services to durable goods buoyed by a swift economic recovery in many parts of the world, and shortages of both intermediate inputs (such as semiconductors) and labour. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the severe lockdowns imposed in many parts of China in recent weeks present further disruptions that will take time to unwind, and which have important consequences for growth and inflation. We find that quarter-on-quarter euro area GDP growth in Q1 2022 could have been almost 0.7 p.p. higher in the absence of the negative supply shocks to global supply chains. In this report we discuss the supply chain disruptions stemming from the lockdowns in China in particular and their implications for the global (and particularly euro area) economy.

Signs of pressure

Global trade indicators have been carefully tracked in recent months in search of signs that the above-mentioned supply and demand imbalances, which have led to delayed delivery times, sky-high shipping costs and broader inflationary pressure, might be starting to ease. Indeed, very early signs of such easing could be seen in early 2022, with traffic in California ports returning to levels not seen since November 2020, traffic in the Shanghai and Zhejiang ports also declining steadily through mid-March, and some shipping price indices (such as Chinese container freight rates) starting to moderate from still very elevated levels. All this led to a decline in the New York Fed’s global supply chain pressure index in January and February of this year (figure 1).

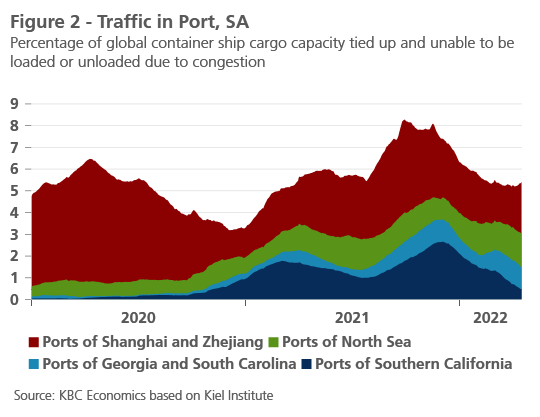

The situation has changed significantly since February, however. Not only has the war in Ukraine disrupted trade activity in the region and led to soaring energy (and therefore higher transport) prices, but severe lockdowns in several Chinese cities since mid-March are also likely to lead to further bottlenecks that will take more time to unwind. Indeed, the impact of these lockdowns, which began in Shenzen in mid-March and in Shanghai in late-March, are not yet included in the Fed’s supply chain index, which only runs through February. Higher-frequency data, like traffic in the ports of Shanghai and Zhejiang, point to growing problems (figure 2). The weekly data suggests that while bottlenecks likely started to build in late-March, the situation has only deteriorated further in April as Shanghai continues to face strict anti-covid measures. The implications of temporary factory closures and congestion in Chinese ports for the global economy are difficult to fully quantify at this stage given several unknowns, including how long the restrictions will remain in place and how policymakers will deal with covid outbreaks going forward. However, some qualitative and quantitative insights can be pulled from earlier supply-chain disruptions in 2020 and 2021.

Global Implications

The sharp rise in container shipping costs at the end of 2020 coincided with rising port congestion elsewhere in the world. To some degree this was the result of higher trade volumes as the recovery progressed at a rapid pace (leading to strong surges in demand for goods), but it also reflected knock on effects from disruptions during the earlier stages of the pandemic; high demand for container ships couldn’t be met because the containers simply weren’t in the right place. What this suggests is that the rising port congestion in China could lead to port congestion elsewhere in the coming months.

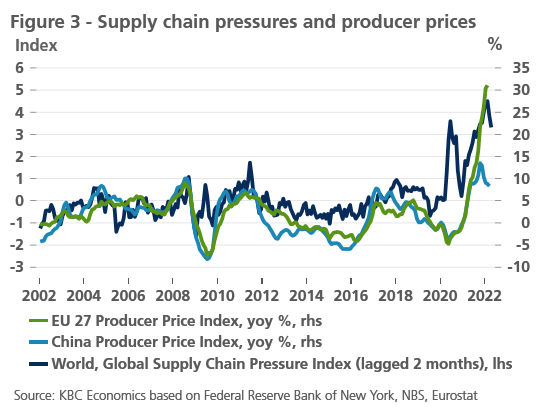

Second, more supply disruptions mean more inflationary pressures, particularly for producer prices (figure 3). A study by the ECB released in August 2021 found that supply chain shocks on inflation persist for six to nine months.1

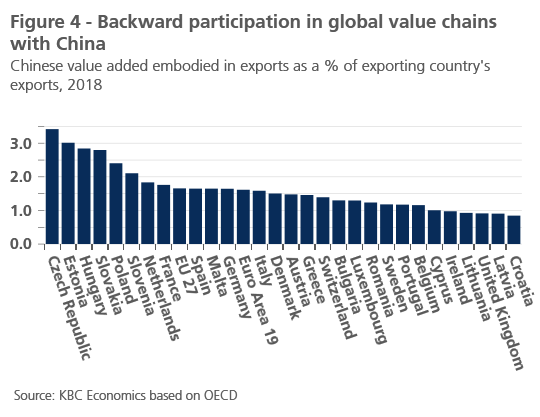

Third, supply disruptions for particular parts can weigh on activity further downstream (as was the case with the global chip shortage and its impact on European automotive industries, for example). The European economies that are most exposed to such disruptions from China (i.e., the economies with companies downstream from Chinese producers) are generally those in Central and Eastern Europe (Figure 4). This makes the lockdown situation in China an additional headwind for some of the European economies that are already most vulnerable to developments related to the war in Ukraine.

Demand side considerations

The same ECB study mentioned above, however, also highlights the demand-side factors playing a role in supply chain disruptions. It found that two-thirds of the increase in supplier delivery times (measured by PMIs) over the 6-months prior could be attributed to the economic recovery and consequent higher demand, versus one-third attributed to supply chain issues. This is important in the context of the current situation; growth in global trade remains elevated but has come down substantially from the highs reached in 2021 (figure 5). Meanwhile, soaring inflation, the war in Ukraine, and monetary policy tightening is expected to put a damper on activity in major economies (such as the euro area and US). On top of this, the lockdowns in China present a major headwind to economic activity, and given problems present in the real estate sector, an extremely swift rebound out of the current situation – as was the case after China’s first period of significant lockdowns back in 2020 – is less likely. All this suggests that a normalising demand situation needs to be considered together with the new supply side disruptions.

A quantitative view

Following previous quantitative analyses of global supply chain issues (see Global supply chain disruptions continue to hamper European industrial recovery and Update: global supply problems, additional supply shocks in the fourth quarter of 2021), we make an update of the estimated impact of these disruptions on euro area GDP for the first quarter of this year based on currently available data. We calculate the supply and demand shocks that led to the already mentioned supply chain disruptions and to what extent these negative supply shocks of the past quarters have affected euro area growth.

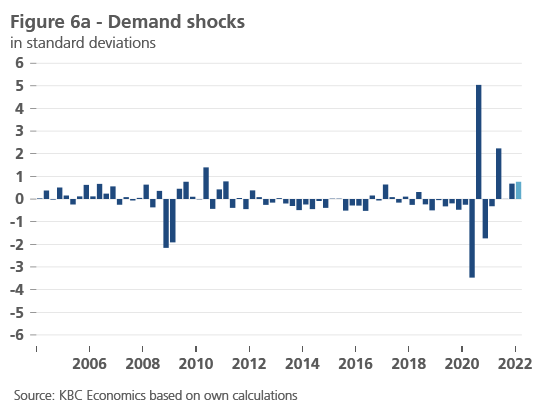

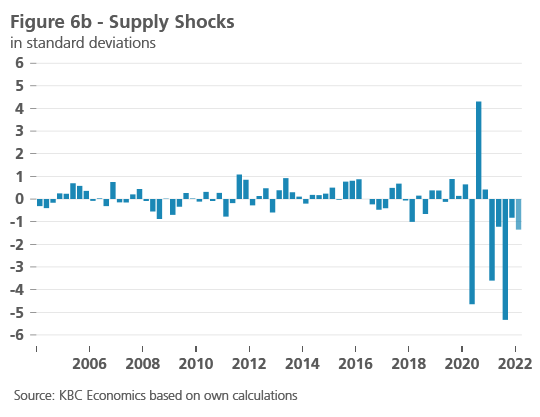

The analysis of these shocks is straightforward, as the results are similar to those of the last quarter of 2021; In Q1 2022, a combination of positive demand shocks and negative supply shocks led to further problems in global supply chains. This included relatively strong positive demand shocks (figure 6a) as a result of a further post-covid recovery, a continuation of the series of negative supply shocks (figure 6b), resulting from the Chinese covid policy and the Ukrainian war, and a combination of shocks which further raised price levels.

In line with previous reports, we also calculate the effects on European growth. Figure 7 shows the cumulative effect on euro area growth of the supply shocks that have occurred since the start of the pandemic. We find that quarter-on-quarter euro area GDP growth in the first quarter of this year could have been almost 0.7 p.p. higher (median estimate) in the absence of the negative supply shocks to global supply chains. The estimates for the coming quarters only include the effects of supply shocks that have already taken place. Additional negative supply shocks during the rest of the year (such as a feared strict lockdown in Beijing), would worsen the estimates for the coming quarters.

Conclusion

Supply chain disruptions continue to be a major feature of the global economy, with important negative implications for growth and upside implications for inflation. There are both supply-side and demand-side elements that have been at play since the early days of the pandemic, and such disruptions have lingering effects that can take several months to unwind. However, relatively new shocks are also playing an important role, including the war in Ukraine and the covid lockdowns in China. In the case of China, high-frequency indicators suggest problems started to mount at the end of March and will likely become more apparent in the coming months. Given uncertainty related to how long current lockdowns will last and whether new lockdowns in other major cities (such as Beijing) will be introduced, further disruptions to global supply chains remain an important risk.

1. Supply chain disruptions and the effects on the global economy