Russia’s economy: resilience meets poor potential

The Russian economy has outperformed most of its regional peers after more than a year into the pandemic, helped by a favourable economic structure and robust macroeconomic buffers. While Russia stands out as one of the least vulnerable economies across emerging markets, its long-term growth prospects are sluggish. This is due to long-standing structural constraints, including excessive reliance on hydrocarbon production, a high government footprint on the economy and weak institutions. Furthermore, uncertainty regarding sanctions is set to remain a lasting factor for the Russian economy even under the new US administration. Overall, Russia’s post-pandemic growth outlook remains weak and insufficient to ensure income convergence with advanced economies in the long run.

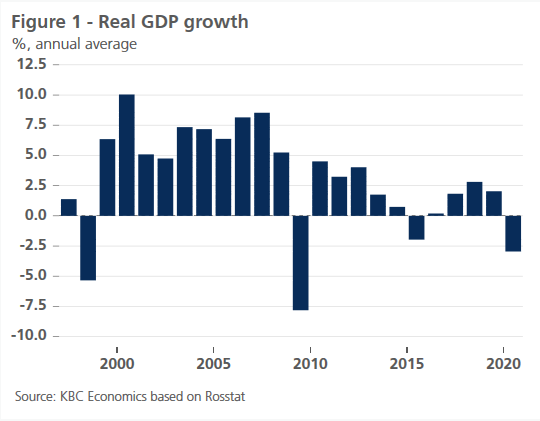

More than a year into the pandemic, the Russian economy has outperformed most of its regional peers. Despite an unprecedented collapse in private consumption, coupled with shrinking export revenues from lower oil prices, the economy contracted by a relatively modest 3.0% in 2020, showing more resilience than during the Global Financial Crisis in 2009 (figure 1). A somewhat limited economic downturn was due to a favourable economic structure (considering the specifics of the pandemic shock) with a relatively small service sector, as well as robust macroeconomic buffers in place.

Robust macroeconomic buffers

The latter is a result of the authorities’ efforts in the aftermath of the 2014-2015 crisis caused by a double shock of collapsing oil prices and international sanctions related to Russia’s military interventions in Ukraine. In order to increase resilience to external shocks, the authorities have pursued a prudent macroeconomic policy mix with restrictive fiscal and monetary policy. Importantly, strong public finance and low government debt allowed the government to implement a sizable fiscal support package of 4% of GDP in 2020 without jeopardising fiscal sustainability. At the same time, considerable foreign exchange reserves, standing at USD 573 billion in March 2021, provide another robust shock-absorber if necessary. Coupled with a strong external position and low foreign liabilities, all this has significantly increased resilience of the Russian economy, now standing out as one of the least vulnerable in emerging markets (see also KBC Emerging Markets Quarterly Digest: Q2 2021).

Anaemic potential growth

The Russian economy nonetheless remains plagued by a mix of long-standing structural constraints. These significantly dampen long-term (potential) GDP growth currently estimated to be just around 1.5%, well below the peer economies. Despite some steps towards diversification, the economic model continues to be excessively reliant on oil and gas production, which is responsible for more than 60% of exports and 40% of federal budget revenues. Furthermore, the government footprint remains high with the state accounting for more than a third of gross domestic product and almost half of total employment, both undermining the competitive environment. Along with weak institutions, a shrinking workforce, and a poor business climate, this weighs on private investment and weakens productivity gains.

Moreover, international economic sanctions adopted by the US and the European Union since 2014 have hampered productivity growth too by banning the import of new equipment and technology transfers from abroad, as well as by increasing uncertainty. In April 2021, the Biden administration further tightened the sanctions regime against Russia by prohibiting US financial institutions from participating in primary issuance for ruble-denominated sovereign bonds as a response to Russia’s 2020 election interference and cyber-attacks. We think that the macroeconomic impact of new sanctions is manageable, particularly in the absence of prohibition on secondary market trading. However, with the new measures in place, it is now clear that sanctions uncertainty is set to remain a lasting structural factor weighing on the Russian economy, even under the new US administrations.

Uninspiring growth outlook

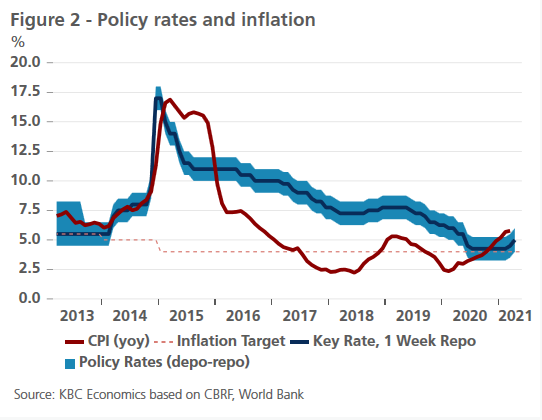

As a consequence of sluggish potential growth, Russia’s post-pandemic growth outlook remains weak. In addition, the authorities have flagged a strong commitment to a fiscal consolidation already in 2021, implying a relatively fast unwinding of anti-pandemic measures. On the monetary front, the central bank has already started the tightening cycle as a response to somewhat stronger-than-expected inflationary pressures and possible downward pressures on the ruble from deteriorating geopolitics (figure 2). All in all, we expect the Russian economy to expand by 3.5% in 2021, boosted by an easing of lockdown restrictions along with mass vaccination. Real GDP growth is then set to moderate to 2.3% in 2022 and further below 2% in 2023, implying a lackluster long-term growth outlook which is insufficient to ensure income convergence with advanced economies.