Franco-German axis without policy coordination is clutching at straws

The election of Macron as French president a year ago and the re-election of Merkel as German Chancellor, rekindled hopes that the Franco-German axis would once again power a leap forward in European integration. Besides good intentions, however, the recent summit between them also laid bare differences in vision: differences that reflect the varying competitiveness of the two countries. A firm foundation for their European political ambitions requires both leaders to pursue policies in their respective countries that bolster their economies and that push in the same direction. Without policy coordination of this kind, the Franco-German axis is simply clutching at straws.

At their recent meeting in Berlin, President Macron and Chancellor Merkel agreed to present a joint proposal at the next European Summit, including strengthening the euro area. It was also apparent, however, that the two are not yet entirely on the same wavelength. Macron focused on greater financial solidarity, while Merkel stressed that any such solidarity must not undermine competitiveness. She wants member states to retain responsibility for their own risks. The two viewpoints are not actually so far apart: they reflect a shared conviction that the euro area needs to be strengthened further. To achieve this, a form of increased ‘solidarity’ – automatic stabilisers – is indeed necessary. However, this must not rob national governments of the incentive to keep their own economies competitive.

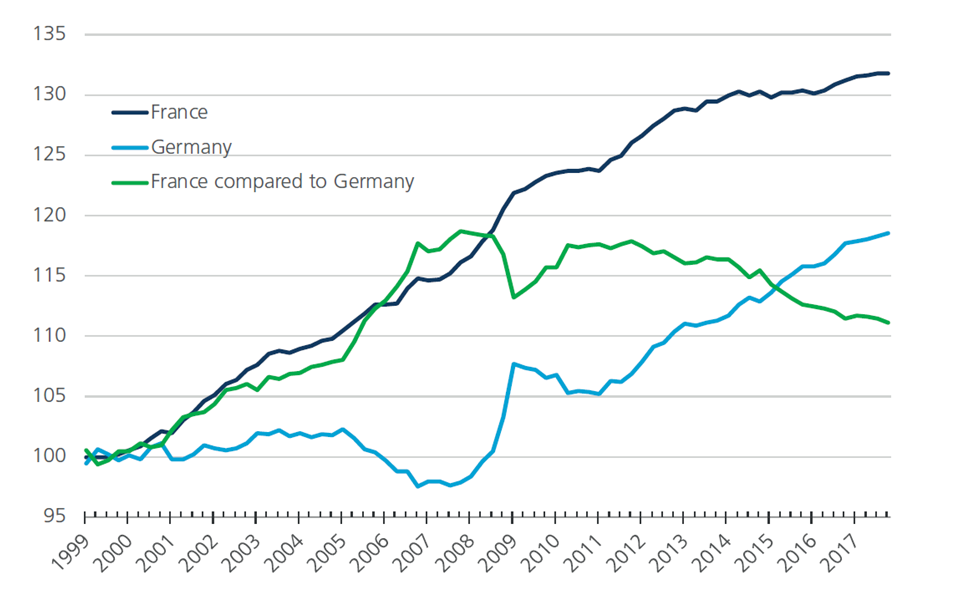

The difference in emphasis between the two political leaders reflects the varying competitiveness of their economies. Aside from numerous qualitative elements, wage costs and labour productivity are an important yardstick in this regard. Cost-competitiveness deteriorates when wage costs rise faster than productivity. Figure 1 shows the evolution of unit labour costs – the ratio of wage costs to productivity growth – in France and Germany since the introduction of the euro. The two have been diverging since as early as the second year. Whereas unit labour costs in Germany remained virtually stable at first and then declined in the period 2005–07, they have risen sharply in France. On the eve of the Great Recession, for instance, France had a pay handicap of just over 18% compared to Germany. Fundamental German labour market reforms, including heightened flexibility and falling wage costs, were decisive in this regard. They enabled Germany to increase its share of globalising international trade by 10%, while France lost 20% of its market share. Germany turned a current account deficit of 1.5% of GDP at the turn of the century into a surplus of almost 7% in 2007. A small deficit arose in France.

Figure 1 - Unit labour costs* (* based on hours worked, 1999 = 100)

The Great Recession brought Germany’s growing wage-cost advantage to a standstill. Because of its greater orientation towards foreign markets, the German economy was hit harder at first than the French. However, this stronger focus on markets outside Europe meant that economic growth in Germany suffered less than that in France during the subsequent ‘double-dip’ recession in the euro area. This resulted in a much more moderate trend with regards to rising wage costs in France. The trend was also very moderate in Germany, but was still significantly higher than in 1999–2007, enabling France to partially reduce its wage-cost handicap relative to Germany in recent years. This was sufficient to halt the loss of international market share and to stabilise the external deficit. However, there is no sign as yet of a fundamental turnaround suggestive of a substantial recovery in the competitiveness of the French economy. Consequently, economic growth in France has structurally lagged that in Germany since the middle of the last decade. Against a backdrop of historically low unemployment, Germany has been piling up budget surpluses since as early as 2014 and government debt has been falling rapidly. The historically high level of unemployment in France, by contrast, has only fallen gradually, and the country continues to flirt with a budget deficit of 3% of GDP – a level close to triggering European sanctions under Germany’s beloved Stability and Growth Pact.

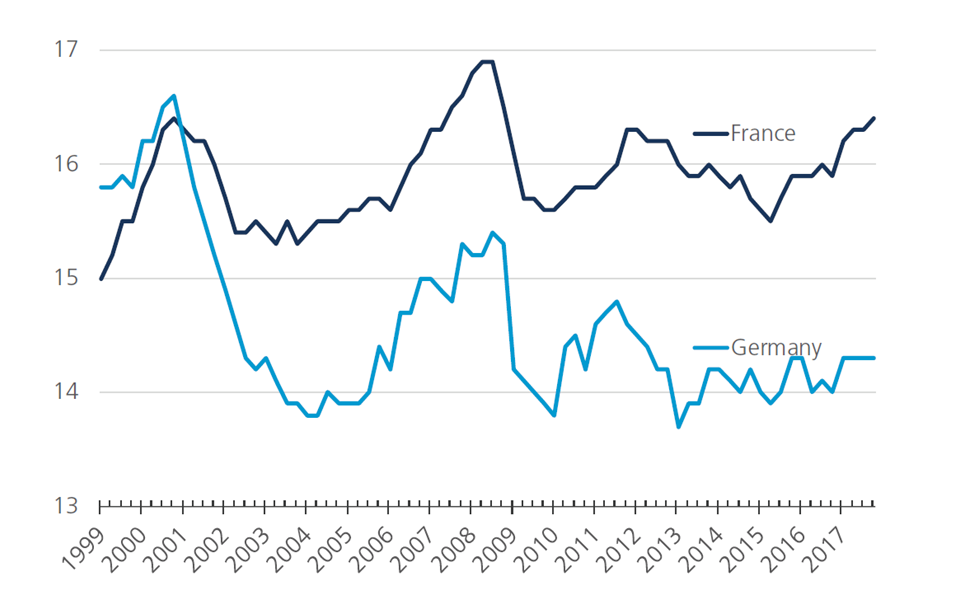

To get Germany onside, it is very much in Macron’s interests to bolster French competitiveness. He now faces the major challenge of persisting with pay moderation and implementing his economic reform agenda. Conversely, Merkel’s plea for competitiveness would also gain credibility if she were to focus German policy more on modernising the economy. This will require her to ratchet up investment, given that German budget and current account surpluses not only reflect the country’s strong competitiveness, but also an unduly low level of investment. Investment in Germany has increasingly lagged that in France in recent decades (Figure 2). With populism on the rise, it will be a challenge for the weakened German government to channel these surpluses primarily into a structural reinforcement of German growth rather than into less productive consumer spending. But this is necessary not only for Germany, but also for the entire euro area – stronger German growth would, after all, trickle through to other countries too, making their own structural reforms that much easier.

Figure 2 - Investments, excluding housebuilding (% of GDP)

In his pursuit of a Franco-German axis, Macron is rightly going all out for a grand vision of the euro area’s future. He can count in this regard on a substantial parliamentary majority. A politically weakened Angela Merkel will have to continue to manoeuvre cautiously in small steps. She is therefore creating the impression that it’s her job to keep the enthusiastic Macron’s feet on the ground. A firm foundation for their European political ambitions is that both countries bolster their economies by appropriate domestic policies and push them in the same direction. The stronger the economy, the stronger the potential support for ‘solidarity’. And the narrower the gap between economies, the less likely it is that any recourse to that ‘solidarity’ will actually be needed. In such a perspective, the necessary bolstering of the euro area is likely to be achieved more readily. Without a coordinated domestic economic policy, the Franco-German axis will simply be clutching at straws.