What to do with Russia's frozen foreign exchange reserves?

24 February marked the second anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. In addition to the human suffering it caused, Europe faces the challenge of finding sufficient funding to help Ukraine. Russian foreign exchange reserves in G7 countries, which were frozen as a sanction, are coming into focus in this regard. Most of the frozen foreign exchange reserves in Europe are in Belgium at the securities depository Euroclear. Possible courses of action under consideration include using the interest income from reinvestments of matured Russian assets, confiscating the capital itself or using the frozen assets as collateral for Ukrainian loans. The latter two options are likely to create legal problems because they touch on property rights. Skimming interest income on reinvestments is more legally defensible. However, confidence in the euro as an international reserve currency could suffer. An empirical study by ECB economists suggests, though, that since the Russian invasion, geopolitical considerations have not caused significant reallocation away from traditional Western reserve currencies, even among countries aligned with Russia and China.

24 February marked the second anniversary of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Apart from its devastating effect on Ukraine, it also had far-reaching consequences for the EU. In addition to direct financial-military support to Ukraine, both bilaterally and through the EU budget, the common trend throughout the policy responses in the EU has been to boost the defence budget. It started as early as 2022 with the announcement by German Chancellor Scholz of an off-budget investment portfolio of 100 bn EUR. Estonian Prime Minister Kallas this month made the same proposal (100 bn EUR) for the EU as a whole. At the same time, European Commission (EC) Chairwoman von der Leyen called for a genuine EU defence policy with EC financial support, inspired by the role the EC played during the pandemic and in the aftermath of the energy crisis.

Financing those ambitions at the EU level will require new debt issuances, along the lines of what happened for NGEU funds. This would increase the liquidity of a full-fledged EU bond market, and thereby also promote the attractiveness of the euro as an international reserve currency (see also KBC Research Report of 9 February, 2024).

Russian FX reserves at Euroclear

The ECB will not be able to assist this time with government bond purchases as it did with PEPP during the pandemic. The pursuit of price stability no longer allows this. Further support from the US is also far from assured. Hence, the EU is also looking at the foreign exchange reserves of the Russian central bank, which are frozen under the sanctions imposed by the G7. Most of the frozen reserves (191 bn EUR out of a total of about 260 bn EUR) are at the securities depository Euroclear in Belgium.

The EU already reached an agreement that the ‘windfall gains’ Euroclear makes on those frozen assets will be skimmed off in favour of Ukraine. The arrangement will apply going forward so the 'windfall gains' Euroclear reported before 2023 on Russian frozen assets will thus not qualify. To illustrate, the 'windfall gains' on all Russian frozen assets (i.e., not just those of Russia's central bank) in 2023 were about 4.4 bn EUR. These 'windfall gains' arise when frozen assets reach maturity and the cash redemptions cannot be disbursed due to sanctions, generating unexpected interest income for Euroclear. According to the legal consensus, this interest income on investments past maturity date is itself owned by Euroclear and can therefore in principle be kept without violating Russian property rights. In part, this is already done indirectly by the Belgian tax authorities through the corporate tax Euroclear pays on its sharply increased corporate profits.

The ECB is reluctant in its approach towards the frozen foreign exchange reserves. It believes close coordination between the EU and the G7 is crucial. At her March press conference, ECB President Lagarde reiterated that the monetary order and rule of law must be respected. In particular, the ECB warned of the potential impact on confidence in the euro as an international reserve currency. This could lead to other non-G7 central banks diversifying their reserves into non-euro denominated assets, higher financing costs for EMU governments and even an impact on trade flows.

To confiscate or not?

The US, on the other hand, proposes to confiscate the reserves themselves, as an advance payment on future reparations paid by Russia to Ukraine, demanded by the G7. However, there is no obvious legal basis for such unilateral expropriation so far, which would almost certainly lead to legal challenges. Hence, European G7 members are not in favour of this course. As a compromise, the Belgian government is proposing to use the frozen assets as collateral for Ukrainian loans, which could be called upon to repay these bonds at maturity if Russian reparation payments fail to be made. According to Euroclear president Mostrey, however, that comes very close to implicit confiscation, with all the legal uncertainty associated with it.

So, for now, it looks like only the plan of skimming 'windfall gains' will be implemented. But even that in itself is a use of the status of reserve currencies as an economic weapon (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 19 May 2022). Indeed, international investors' confidence in the security of reserves is one of the fundamental prerequisites for a reserve currency.

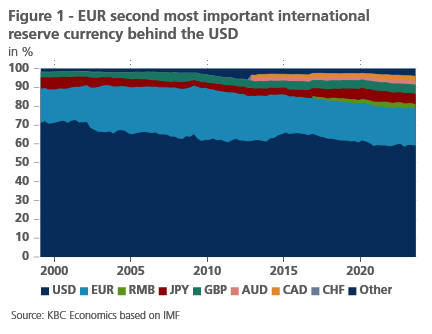

Over time, however, such a trend could erode the foundations of the current international monetary system. Nevertheless, little is likely to change in the short term, in the absence of a plausible alternative to the euro and especially to the U.S. dollar (see Figure 1). International investors are also well aware that countries such as Russia and China themselves have fewer reservations than the US and the EU about using their own currencies as a means of political pressure. That conclusion is supported by a recent ECB study, which, for the period between the fourth quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2022 (roughly the first year of the Russian invasion), finds no correlation between geopolitical affinity with China and Russia and an above-average diversification of foreign exchange reserves into currencies that are not part of the IMF's SDR basket. While that basket includes the renminbi, that currency has the disadvantage of limited convertibility for international investors. Any geopolitical considerations in the countries concerned were rather reflected in the accumulation of gold reserves.