US backs away from dreaded fiscal cliff

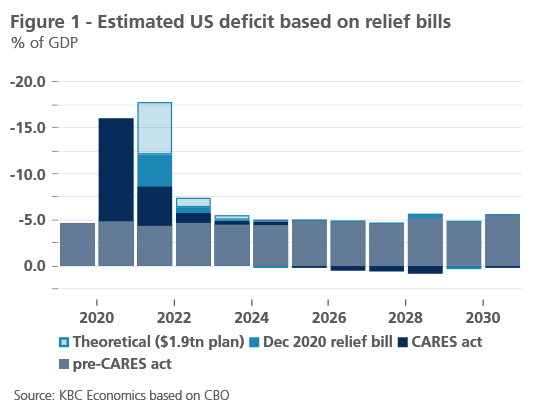

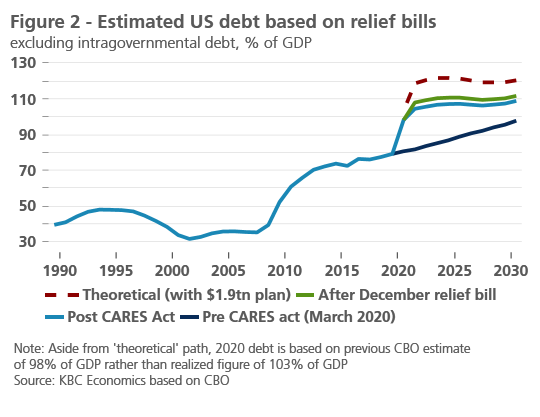

Like many countries around the world, the United States introduced significant fiscal stimulus measures in 2020 to combat the effects of the Covid-19 crisis. This included the CARES act ($2.2 tn), signed in March 2020, and a second major stimulus package ($900 bn), signed in December 2020. As a result, the fiscal deficit rose to 16% of GDP last year and, based on estimates made by the Congressional Budget Office, will remain relatively wide in 2021 at 12% of GDP. Now, President Biden is pushing for a further coronavirus relief bill worth $1.9 tn. Though it is far from certain that all aspects of Biden’s proposal will make it into the new bill, based on a rough analysis, we estimate that the full proposal could result in a fiscal deficit close to 18% of GDP in 2021. This suggests that the US economy would not face any so-called fiscal cliff this year. At the same time, the additional spending measures could increase the public debt ratio (excluding intragovernmental debt) to 118% of GDP this year.

A headline year for fiscal stimulus

There is little doubt that the significant stimulus measures (on both the monetary and fiscal fronts) rolled out in 2020 have helped cushion the economic fallout from the pandemic. Policymakers appear to have learned from past crises that responding too slowly or on too small a scale can be costly. Even the US Congress, which is deeply divided along partisan lines, managed to pass $2.8 trillion (13% of GDP) worth of stimulus measures in 2020 (including the March 2020 CARES package and the December 2020 relief bill).

With the pandemic dragging into its second year, and with vaccination campaigns underway in advanced economies, however, there are increasingly divided opinions about how much more fiscal stimulus is necessary. The recovery is clearly underway, but it is a fragile recovery surrounded by downside risks. Such risks include the ongoing spread of the virus and its new variants, uncertainty in terms of the speed of the vaccination campaigns, and a lack of clarity on how much scarring the economy will have endured when it eventually leaves the pandemic behind.

The good news for the US economy is that the December 2020 relief bill already reduced the size of the potential ‘fiscal cliff’ (i.e. a steep drop in government spending or expiration of tax cuts) in 2021 versus 2020 (see the solid light blue area of Figure 1). This is based on a recently released assessment by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) that concludes that the December relief bill will increase deficits by a cumulative $868 bn between 2021 and 2030, with about 85% of that increase occurring in 2021.1 This raises the estimated fiscal deficit for 2021 from 8.6% of GDP (according to the CBO’s September 2020 estimate) to roughly 12% of GDP.

However, even this estimate by the CBO may soon be outdated if the Democrats manage to pass at least some of Biden’s ambitious $1.9 trillion plan.

Though we don’t yet have concrete details on what will make it into the bill, how such spending will be structured, or what the eventual impact on US revenues and spending will be, we can extrapolate from the analysis in the latest CBO update to get a sense for how this new proposal might affect the US deficit and debt levels. This is supported by the fact that many of the proposals in Biden’s new plan are extensions or expansions of measures included in the December bill (particularly the extension of enhanced unemployment benefits and additional stimulus checks for individuals).

For example, the December relief bill included $600 checks to individuals under a certain income level. The CBO estimates that this will increase budgetary spending by $163 bn in 2021 and $277 mn in 2022. The new proposal includes further checks worth $1,400. Therefore, by multiplying the CBO’s estimates by a factor of 2.3 (or 14 divided by 6) we can roughly assume that this provision will cost $375 bn in 2021 and $637 mn in 2022. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates that this provision could cost $463 bn in total, suggesting that our estimate is on the low end (likely due to the fact that Biden wants to expand the pool of eligible receivers to include adult dependents and families with mixed immigration status). However, given that there are growing proposals to further restrict the pool based on income levels, such an underestimation seems reasonable.

We do a similar exercise for other elements of the new proposal, including an extension of enhanced unemployment benefits through September, $160 bn to combat the virus, $15 bn in grants for small businesses, $170 billion for schools, $350 bn for state and local governments, $30 billion in rental and utility assistance, and an extension of enhancements to the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program through September. We also factor in the impact that increased tax credits may have on the revenue side (e.g. the Tax Foundation assumes that an expansion of the child tax credit will cost $104 billion and the JCT estimates that an expansion of the earned income tax credit will cost $10 bn).

Adding all of these rough estimates together, we arrive at an estimated cumulative effect on the deficit through 2030 that totals $1.6 trillion. If we combine these effects with those estimated by the CBO in December (after the second package was passed) and apply them to the budget estimates published by the CBO in September 2020, we arrive at a new path for the deficit and debt. If Biden’s proposal were to pass in its entirety (again, such an outcome is uncertain), the deficit could rise to as much as 17.8% of GDP in 2021 before narrowing to 7.4% of GDP in 2022 (transparent blue area in figure 1). This deficit path would bring the public debt ratio (excluding intragovernmental debt) to 118% of GDP (up from 103% of GDP in 2020) (figure 2). It must be stressed, however, that these figures are illustrative estimates only and not forecasts, as they don’t account for the multiplier effect of fiscal spending.2 Still, even accounting for the multiplier, there would be no fiscal cliff in 2021, but a sizable one the following year, which would hopefully be balanced by a continuing economic recovery in a post-pandemic world.

1 https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56961

2 E.g., the CBO estimated that in the short-term, every dollar added to the deficit from prior Covid-19 spending would increase GDP by 58 cents (The Effects of Pandemic-Related Legislation on Output (cbo.gov)