Uncertainty over Fed policy pushes US rates higher

Since the beginning of 2021, the US 10-year bond yields have risen sharply to around 1.50%. The relatively stable inflation expectations in the same period indicate that this is mainly an increase in real yields. These real yields probably did not rise so much as a result of higher expected policy rates, but mainly as a result of the increased uncertainty about these policy rates, which caused the term premium to rise. Clearer Fed communications could therefore help to avoid a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum. While Japan’s central bank may be able to largely neutralise the spill-over from higher US yields through its policy of explicit Yield Curve Control, the ECB’s policy toolbox is limited to its purchase programmes and forward guidance.

Since the beginning of 2021, US 10-year government bond yields have risen sharply by more than 70 basis points to around 1.50% at the end of February. This increase was not only limited to the long end of the yield curve, but also applied to the medium-term maturities. For example, five-year yields rose by more than 40 basis points to around 0.80% over the same period. While neither the level of bond yields nor the steepness of the yield curve are at an exceptionally high level so far, the speed of the increase is all the more remarkable. This raises the question of what is driving this exceptional movement.

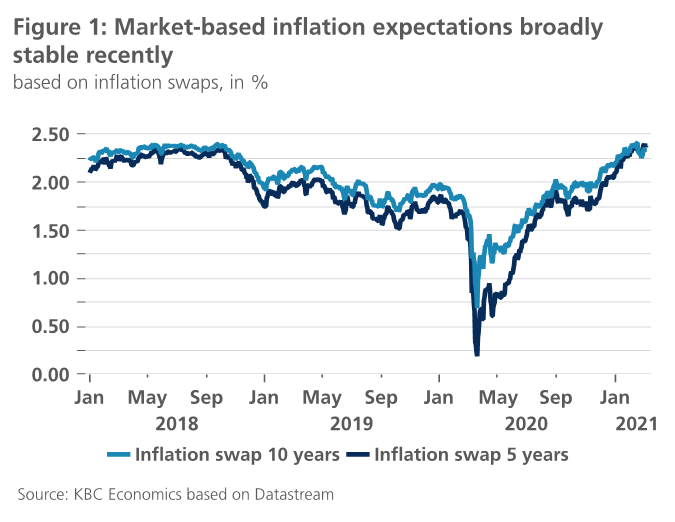

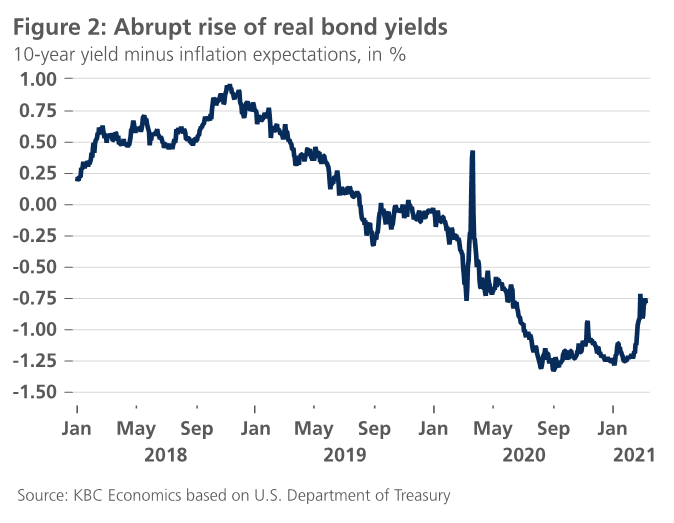

First, the relatively stable trend in market inflation expectations since the beginning of the year suggests that they are not the main driver of higher interest rates (Figure 1). Rather, higher bond yields reflect higher real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. It is important to note that, even after the recent rise, real US interest rates are still clearly negative, i.e. at particularly low levels (Figure 2).

The next question then is, which component of real interest rates was the main determinant of the rise ? According to the so-called ‘extended expectations hypothesis’ of the term structure of interest rates, we can interpret an interest rate with a longer maturity as the compounded average of expected future short-term interest rates plus a risk premium, the so-called ‘term premium’. This premium serves, among other things, to compensate for the risk that these expectations prove to be wrong. For risk-neutral investors, the required risk premium is normally zero percent, while for risk-averse investors it should normally be positive. A negative term premium, as was the case in 2019 and 2020, is rather exceptional and often indicates other factors or anomalies. This may have been caused, for example, by the disruptive effect of large-scale central bank asset purchase programs or by abundant excess liquidity on the market.

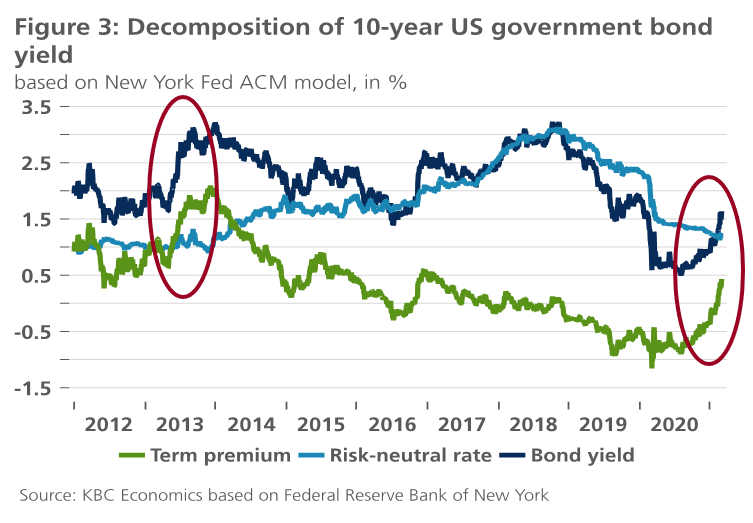

To examine the recent evolution of the term premium, we rely on the New York Federal Reserve’s ACM model. In this model, the observed long-term interest rate is decomposed into its risk-neutral component (i.e., the expected future short-term rates) and the term premium. That ACM decomposition in Figure 3 suggests that the recent rise in bond yields was almost entirely due to the rise in the term premium. The expected development of the future short-term interest rate (the so-called ‘risk-neutral’ interest rate) played a lesser role. The model therefore suggests that, although the market still expects a largely unchanged policy rate from the US central bank (Fed) in the near future (in other words, no increase in the ‘risk-neutral rate’), the market has become less certain about this. Consequently, the market demands a higher compensation for taking that risk (in the form of a higher term premium).

Moreover, the normalisation of the term premium - it has turned positive again, at least in the specification of the ACM model - may also be related to a possible future tapering of bond purchases by the Fed. These bond purchases have played an important distorting role in artificially pushing down the term premium over the past decade. The Fed’s current forward guidance on its bond purchase programme may have contributed to increased market uncertainty about the exact timing of such tapering. If this hypothesis is correct, the further course of US bond yields will depend on whether and when the Fed provides more clarity on this. Figure 3 also illustrates that the abrupt rise in bond yields and term premium during the so-called ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013 was an instructive example of what can happen to bond yields if market expectations of Fed policy do not sufficiently match the central bank’s actual policy intentions.

Due to the strong integration of international bond markets, US yields also lifted German yields, albeit to a more limited extent. Even the Japanese 10-year yield rate rose above 10 basis points, despite the explicit yield target of 0% set by the Bank of Japan. However, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) can probably prevent a further rise in Japanese yields relatively easily through its policy of Yield Curve Control (YCC). As part of its YCC policy, the BoJ promises to buy or sell whatever amount of government bonds necessary to keep yields around 0%.

The ECB is in a more difficult situation. A YCC policy is not an obvious choice for the ECB in the absence of a sufficiently large pan-European bond market. There is probably no consensus on ‘spread control’, which would involve setting a target for all euro area government bond yields. The ECB will therefore have to make do with its existing purchase programmes (especially the PEPP) until further notice, supplemented by forward guidance on its policy rate. For the rest, the ECB can only hope that US yields will not rise too quickly and too sharply.