Turmoil in the British bond market

British bond yields faced a rollercoaster ride in the last weeks. The government’s ‘minibudget’ announcement caused a 70bp rise in 10Y gilt yields in a week time. Pension funds faced liquidity issues and the Bank of England (BoE) had to step in. A new Chancellor and new budget announcement calmed the markets. Yet it also undermined the Prime Minister’s authority, and she was therefore forced to resign. Though it’s unsurprising that high deficit spending pushes bond yields upwards, the market reaction was surprisingly big. The diminished role of the pound could partly explain this. However, the market’s reaction also shows that as interest rates have moved far above the zero lower bound, government spending doesn’t have the same GDP impact as before. That has implications for policy makers around the world.

Introduction

Liz Truss’s premiership will go down as very short but also nerve-racking. Five weeks ago, her Chancellor of the Exchequer Kwai Kwarteng announced a ‘mini-budget’ containing a staggering £45bn of new spending and tax cuts for this fiscal year. Markets panicked. The pound slid to £1.07/USD, a record low. 10Y gilt yields rose by 70bp in a week’s time. Pension funds faced big margin calls which some were unable to afford. The BoE even had to step in to restore confidence by committing 65 billion GBP to stop a fire-sale in long-term gilts. Liz Truss was then forced to sack the Chancellor and replaced him with Jeremy Hunt. He proposed a new budget which effectively reversed most of the ‘mini-budget’ proposals and calmed markets. Yields dropped back to less than 4%. The whole episode, however, undermined faith in Liz Truss’s ability to steer the economy and the government at large. The popularity of the Tories dipped to record lows. In recent polls, Labour has a stunning 32 pp lead over the Tories. Liz Truss’s resignation was thus all but inevitable.

Sharp market reaction is a game changer

The fact that high deficit spending pushes government bond yields upwards is logical. High deficit spending increases the supply of government bonds, drives up inflation, and can negatively impact a country’s creditworthiness. Nonetheless, the sharpness of the market reaction was surprising. Britain’s debt to GDP stood at 95.3% of GDP in 2021, compared to 128.1% in the US and 95.6% on aggregate in the eurozone. It also has its own currency and thus its central bank can intervene freely when government bonds come under pressure, in contrast to the eurozone, where these interventions are more politically fraught.

The diminished role of the pound is one reason markets reacted so heavily. As the Brexit saga caused huge volatility in the pound’s exchange rates, it lost somewhat its role as a safe haven and is less used as a reserve currency. The resulting lower demand and less frequent trading of gilts causes upward pressure on yields and increases their volatility. Foreign investors also hold 25 to 30% of the UK’s debt, and they are more likely to rush to the exit when things go south.

Nonetheless, these facts do not explain why Britain has experienced such a big gilt sell-off right now in particular. Following the mini-budget, the UK’s National Institute of Social and Economic Research (NIESR) calculated that the UK’s budget deficit would hit 8% in this financial year. Yet this deficit is not exceptionally high by recent standards. In 2008 and 2009, the UK deficit reached 10% and 9.2% respectively and in 2020 it even reached 12.8%, yet no major bond sell-off then occurred. To understand the root cause, we have to look at the global macroeconomic environment.

Excess savings pushed down rates during the GFC

In 2008 e.g., Britain, along with many of its peers, was hard hit by the global financial crisis. After the global panic was over, all players in the economy faced a prolonged hangover for several years. Private individuals and companies faced a debt overhang and saved more to improve their financial health. Banks, meanwhile, tightened their lending requirements and reduced lending to increase their capital buffers.

As all players in the economy saved together, interest rates declined sharply. The Bank of England reduced its policy rate to 0.5%. However, that wasn’t enough to stave off a deep recession. In 2009, GDP declined by 4.2%. To stave off a recession in these circumstances, interest rates would need to go much lower. Research by Jing Cynthia Wu, for instance, found that rates still needed to be as low as -6.5% in Britain in 2013 (5 years after the Great Financial Crisis)1 . Central banks could in theory set their rates at these low levels. The problem is that banks are unlikely to pass these rates on to the consumer as consumers could avoid the negative rates by withdrawing their cash. Cutting rates when rates are already in negative territory will therefore barely have any effect on aggregate demand. Unconventional central bank policies such as quantitative easing can help, but they will not fully circumvent the constraint posed by the zero lower bound. Between 2009 and 2021, the BoE bought £895 billion worth of bonds through QE. However, while M02 more than quintupled since 2008, lending volumes barely moved (see figure 1).

In such an environment, the government had to step in. As the private sector became a big net saver and central bank policy became ineffective, only government could act as a net borrower. Its investments had a big positive effect on GDP as unemployment was high (7.6% in 2009). Furthermore, ample savings flew into banks, pension funds and insurance companies, while private investment opportunities and borrowing dried up. A large proportion of the extra savings they received were invested in government bonds. This explains why yields on UK government bonds declined in 2009, even though the government ran massive budget deficits and monetary policy rates were close to 0%.

A new economic paradigm

In 2020, the UK’s economy again went into excess saving modus. As people were stuck at home, spending opportunities were limited, and the private sector again saved massively. Notwithstanding the UK government’s double-digit deficit, yields on 10Y gilts reached an all-time low of 0.14%.

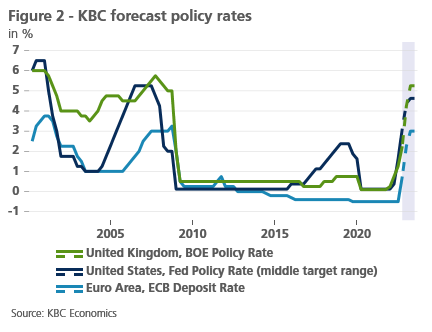

That situation changed dramatically when the economy reopened in 2021. Consumers, flush with cash, went on a spending spree, while governments around the world kept the tabs open. Meanwhile supply constraints and high energy prices drove up inflation. Labor markets also became very tight, with unemployment reaching 3.5% as of today. Interest rates went far above the zero lower bound, as central banks tightened their monetary policies around the world (see figure 2).

In such an environment, government spending will simply crowd out private spending and employment. It will also drive up nominal wages and inflation, drive up yields on bonds, and make government debt increasingly unsustainable. The market’s reaction to Kwarteng’s ‘mini-budget’ was thus well-founded.

Conclusion

The UK Gilt meltdown should serve as a cautionary tale around the world. Now that interest rates are far above the lower zero bound, excessive government spending is not a good answer to solve our current woes. In today’s circumstances, where aggregate demand exceeds supply, it will barely create any GDP growth, drive up rates and inflation, and can potentially cause debt sustainability issues in the future. The new economic paradigm requires new economic thinking.

1 Jing Cynthia Wu, Ji Zhang, 2016, “A Shadow Rate New Keynesian Model”.

2 M0 is het totale geldbedrag (biljetten en munten) dat in handen is van het publiek of in deposito’s die door commerciële partijen worden aangehouden in de reserves van de centrale bank.