Turkish economic recovery: do not get too excited

The Turkish economy has rebounded strongly from its financial crisis of 2018, buoyed by substantial fiscal and monetary stimulus. While these policies have helped achieve short-term stability, prioritizing growth over containing underlying macro-financial vulnerabilities calls into question the long-term sustainability of the recovery. That is to say, the recent financial crisis has not had a cathartic impact, as was the case after the 2001 economic crisis. The Turkish authorities, by contrast, have reverted to the pre-crisis model of credit-driven growth that had contributed to large economic imbalances in the first place. This, coupled with an increasingly interventionist and unorthodox economic policy, is a risky way ahead, leaving the economy vulnerable to negative shocks.

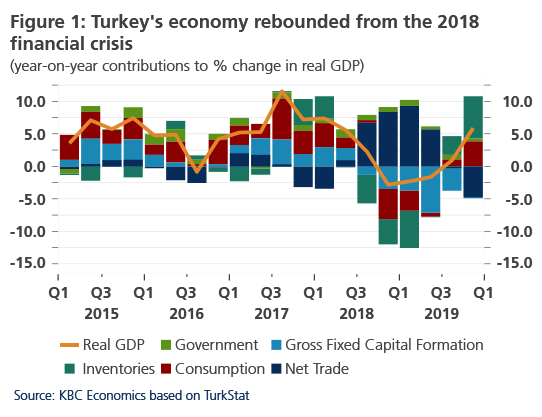

The economic landscape in Turkey improved in the second half of 2019 with growth turning positive in the third quarter after three consecutive quarters of contraction. This came as a surprise to many; the Turkish economy managed to exit the recession that followed the mid-2018 financial shock faster than expected. The cyclical upswing took off on the back of a positive global backdrop, but the economic momentum has been primarily supported by a combination of expansionary fiscal and monetary policy. While these policies have helped achieved short-term stability, the underlying trends are worrisome and far less rosy than what the headline figures might suggest.

The Turkish authorities have prioritized growth…

Since the 2018 crisis, the Turkish authorities have prioritized growth through a mix of large fiscal stimulus, front-loaded monetary easing and state-bank lending. To reboot growth, the government implemented tax cuts as well as a broad range of unorthodox measures (e.g. food price discounts), which led to a substantial fiscal impulse to the economy at around 2% of GDP in 2019, according to our estimates. At the same time, however, the fiscal balance deteriorated sharply, and the deficit remained only slightly below 3% of GDP in 2019 thanks to a one-off transfer of the central bank’s profits (amounting to 1.8% of GDP) and the corporate tax obligation by the central bank to the treasury. This underlines two general trends that are, in our view, problematic; first, a rising tendency by the central bank to support the treasury’s financing; second, an increasing lack of fiscal discipline. Therefore, while public consumption is expected to support the recovery again in 2020, we see a risk of possible fiscal slippage if the ambitious government growth target of 5% is missed.

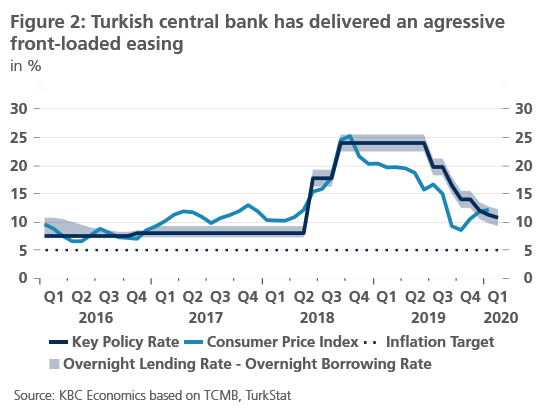

Meanwhile, monetary policy has also been centered on boosting growth, which reflects the gradual erosion of the Turkish central bank’s (CBRT) independence. This was highlighted in July 2019 when President Erdogan fired the governor, Murat Cetinkaya, after a clash over the pace of rate cuts. With the new governor, Murat Uysal, in place, the CBRT has delivered an aggressive front-loaded monetary easing. Since the change in the central bank’s leadership, the CBRT has consistently surprised markets with larger-than-expected rate cuts that cumulatively amount to 1325 bps and brought the key rate to 10.75% amid fast disinflation and relative lira stability (supported by enhanced state bank presence in the FX market).

We expect that the CBRT will maintain an easing bias in 2020, bringing ex-ante real interest rates close to zero. However, with inflation stabilizing around low double-digits and inflation expectations being stubbornly elevated, the room for maneuver is limited. That is to say, the central bank is unlikely to reach the 5% inflation target any time soon as more structural disinflationary effects are, in our view, incompatible with the current monetary policy stance and objectives. Overall, we assume that the CBRT’s easing cycle will continue but with more measured cuts to 9.00% by end-2020. Still, more aggressive easing cannot be ruled out, especially given lingering political pressure from the president, which continues to undermine the central bank’s credibility.

Furthermore, the CBRT has implemented a series of unconventional measures that have helped ease financial conditions materially and triggered a fast credit expansion in H2 2019. The monetary authorities have extended credit guarantees and relaxed macroprudential rules substantially by effectively lowering reserve requirements for banks with year-on-year credit growth above 10%. This initially incentivized mostly state-owned banks to ramp up lending, but more recently private banks have also boosted consumer lending (and to a lesser extent corporate loans). As a result, a sustained credit impulse should support consumption growth through 2020 as well.

…but short-term stability comes at a cost

These growth-enhancing measures will support further economic recovery and might even challenge our current estimate for Turkish real GDP growth of 2.5% in 2020. Nonetheless, prioritizing short-term growth comes at a cost. In other words, stronger economic momentum in the near future does not alter the fundamental picture, i.e. potential growth being undermined by persistent structural weaknesses, leaving the long-term economic prospects darkened.

The progress in containing macro-financial vulnerabilities has been limited since the crisis. After a major external adjustment over the past 12 months, the current account is again deteriorating and slipped into negative territory amid the cyclical upswing and import-led growth. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate remains firmly entrenched in double-digit figures and a sustained fall in inflation seems unlikely. Last but not the least, banking and corporate (external) debt overhang, together with lingering economic uncertainty and low investor confidence, is set to remain an important drag on private investment.

Overall, our view is that the latest developments call the long-term sustainability of the Turkish economic recovery into question. The financial crisis of 2018 has not had a cathartic impact, as was the case after the 2001 economic crisis. The Turkish authorities, by contrast, have reverted to the pre-crisis model of credit-driven growth and reliance on foreign funding that had contributed to large economic imbalances in the first place. This, coupled with an increasingly interventionist and unorthodox fiscal and monetary policy, is a risky way ahead, leaving the economy vulnerable to negative shocks.