Turkey beats peers but faces higher risks

While the Turkish economy was hit hard by the Covid-19 pandemic, it recorded less severe contraction than many of its emerging markets peers in Q2 2020. Furthermore, the recent high frequency indicators all suggest that a rapid economic recovery was underway in the third quarter. This is surprising given the pre-coronavirus vulnerabilities. However, the authorities have again boosted activity by the state-backed lending boom, prioritising growth over containing macro imbalances. This has led to a large current account deficit, as well as a sharp lira weakening. While the central bank has so far reluctantly delivered ‘back-door’ tightening, more needs to be done to contain risks to financial and price stability. On top of macro risks, there are major geopolitical risks, most recently including Turkey’s involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Against such a backdrop, the future path of the economy remains uncertain and likely bumpy. Without a shift to a more orthodox economic policy to tackle the long-lasting structural impediments, the risk of a painful hard landing remains high.

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic triggered a sharp economic contraction in both advanced economies and emerging markets. The Turkish economy plunged by 11% qoq in the second quarter with a broad-based decline across the demand components. While this marks the worst quarter-on-quarter contraction on record, it was not as bad as many feared, and Turkey outperformed many of its emerging markets peers in Q2. Furthermore, the recent high frequency indicators all suggest that a rapid economic recovery was underway in the third quarter. This looks surprising given the fact that Turkey entered the coronavirus crisis as one of the most vulnerable economies, following a fragile recovery path since the 2018 currency crisis.

A massive credit boom drives the economic recovery

There is a good reason to remain cautious about the upbeat headline figures, though. While early lockdown and subsequent fast reopening helped with the mechanical bounce back, the surge in economic activity has been heavily supported by a massive state-backed credit boom. On the back of ultra-low real interest rates, easing credit standards, the expansion of the Credit Guarantee Fund as well as a substantial role of public banks, TRY lending growth increased from 15% yoy in March to almost 40% yoy in September. As such, the authorities have chosen to prioritize growth over containing macroeconomic imbalances—a similar response to the past slowdown.

The flip side of the rapid credit expansion is a further widening of the current account deficit. Among other things, the collapse in international tourist arrivals (-84% yoy over the June-August period) has weighed on export revenues. But Turkey's imports rebounded in a V-shaped manner, showing no signs of major adjustment. This is a striking exception among emerging markets that have mostly seen a sharp external adjustment due to the pandemic-induced recessions. Also, this is particularly troublesome given the fact that the persistent current account deficit has been funded largely by a drawdown in foreign reserves (dropping to USD 41 billion, or 48% yoy), something that is unsustainable going ahead (as long as there are no offsetting non-resident financial inflows) and exacerbating already-elevated external vulnerabilities.

The large current account deterioration is also one of the underlying reasons for continued lira weakness. The Turkish currency has sunk almost 25% against the USD this year to a record low of just below 8.00 USD/TRY, ranking among the worst-performing currencies worldwide. Fundamentally, the lira has also been suffering from negative real interest rates as a result of stubbornly high inflation and low nominal interest rates, as well as the recent trend of dollarization. Residents’ FX deposits in the economy have surged by USD 16 billion to a record of USD 194 billion since the beginning of March, reflecting domestic concerns about the lira. We expect a further structural weakening of the lira above 8.00 USD/TRY by end-2020 and further into 2021.

More needs to be done to contain the risks

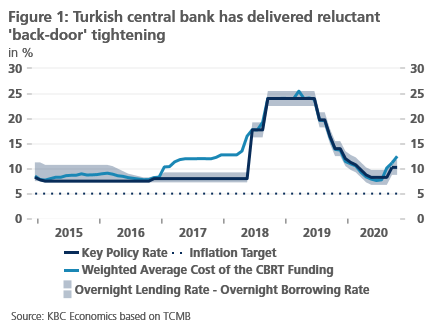

At the same time, Turkey's central bank has gradually become more concerned about financial stability risks stemming from the impact of disorderly lira depreciation on Turkey’s large amount of FX-denominated debt, as well as about price stability risks from high pass-through from the weakening lira. That has prompted the central bank to reverse the easing measures introduced at the beginning of the pandemic and tighten the monetary policy stance. However, the tightening was largely ‘back-door’ by using the late liquidity window to gradually increase the effective cost of funding to 12.47% (as of 20 October) while keeping the official benchmark rate at 10.25% (figure 1).

Additionally, local authorities have somewhat tightened the macroprudential measures to curb lending growth more recently. So far, this has seen only a limited impact as lending growth remains elevated. On the monetary front as well, more needs to be done to contain the risks. The central bank is once again well behind the curve, remaining under the pressure of President Erdogan who has a well-known aversion to higher interest rates. In the 2018 currency crisis, the central bank hiked interest rates to 24.00% to safeguard financial stability. Such a dramatic tightening is not needed for now, in our view, but real interest rates in a meaningfully positive territory are certainly warranted (implying the 1-week repo rate at 14.00% over the 6-month horizon in our outlook).

Heightened geopolitical risks

Importantly, the weakening of the lira has reflected not only adverse macroeconomic developments but also heightened geopolitical risks. After the failed coup attempt of 2016, Turkey's foreign policy has become increasingly more assertive to encourage nationalistic sentiment at home and capitalize on the popularity of these moves at a time of economic weakness. In addition to activities in Libya and Syria, Turkey's regional ambitions have manifested in escalating tensions in the eastern Mediterranean over territorial boundaries and gas deposits with Greece, another NATO member. Most recently, rising tensions have been playing out in the Caucasus’ Nagorno-Karabakh, where clashes have broken out between Turkey-backed Azerbaijan and Russia-backed Armenia. Finally, Turkey still plans to purchase S-400 anti-aircraft missiles from Russia, increasing the risk that the US government could impose sanctions, particularly if Joe Biden wins and takes a tougher stance on Turkey.

All in all, risks are mounting for Turkey both on the macro and geopolitical fronts. While there are signs that monetary authorities are trying to contain some of the risks, the future path of the economy remains uncertain and likely bumpy. Also, the developments of the Covid-19 pandemic will make things more difficult (although official figures show a levelling-off, they provide only a partial record as they do not account for asymptomatic cases). What Turkey needs from a long-term perspective is a shift to a more orthodox economic policy that will tackle long-lasting structural impediments. Otherwise, the room for manoeuvring is becoming increasingly scarce, while the risk of a painful hard landing increases.