Thunderstorm or clearing for the Belgian labour market?

The limited impact, for now, of the pandemic on actual unemployment raises the question of whether the real shock to the labour market has yet to come. Crucial in this respect is whether the still large group of temporarily unemployed can get back to work. As the economic recovery will only gain momentum from the summer onwards, it is likely that many jobs will be lost in the short term, partly due to a wave of bankruptcies. In the longer term, however, we do not have to be so negative about the labour market. But to ensure a more positive outcome, we should already be putting effort into retraining and reorienting employees affected by covid-19 towards new career opportunities.

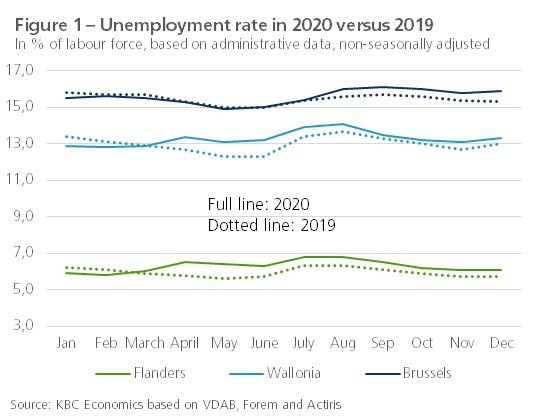

Although covid-19 has weighed heavily on economic activity - at the end of 2020 real GDP was still 4.8% lower than at the end of 2019 - the impact of the pandemic on effective unemployment has remained relatively limited. The unemployment rate (based on administrative figures) was not much higher in any of the three Belgian regions throughout 2020 than in the corresponding months of 2019 (Figure 1). We estimate that more than 60,000 net jobs were lost in Belgium between the end of 2019 and the end of 2020. That is a decrease in annual average employment of only 0.2%. The fact that the labour market has held up well so far is due to the decisive action of the government with support measures that limit direct job losses, including the extension of the temporary unemployment system. At the peak in April last year, 1.2 million Belgians were in that system. Afterwards, that number fell to 0.2 million in September, but has since risen again to 0.5 million at the end of the year. That is about 15% of all wage earners in the private sector.

Labour hoarding cannot last

Sooner or later, the still numerous temporarily unemployed will either return to their previous job, find a new one, or end up in effective unemployment (assuming they do not leave the labour market permanently, which is also possible). Which will prevail will be determined by the speed and intensity of the economic recovery. We assume that the recovery of the Belgian economy will only accelerate from the summer onwards, in line with the completion of the roll-out of vaccination. This implies the risk that a considerable number of people will end up effectively unemployed. We estimate the job loss in 2021 to be around another 60,000 units. This translates into an increase of the unemployment rate (Eurostat definition) from 5.2% at the end of 2019 to 5.8% at the end of 2020 and an estimated 7.2% at the end of 2021.

Rising unemployment will partly result from an increase in the number of business failures. Especially in the sectors heavily affected by covid-19 (catering, events, recreation, etc.) one cannot just switch off and on again activity, as if it were a coffee machine. Many companies are now financially weakened and will ultimately not survive the crisis. According to the latest survey by the Economic Risk Management Group, almost one in ten companies across all sectors considers bankruptcy as (very) likely. It is likely that many surviving companies will also be forced to restructure, which usually involves redundancies. Many leading indicators therefore do not bode well for the labour market in 2021. The employment forecasts contained in the NBB barometer, the consumer expectation on unemployment, the Federgon index on temporary employment, the number of newly available vacancies, etc.: they all still show a worse performance at the end of 2020 or the beginning of 2021 than before the outbreak of the pandemic.

Clearing after the thunderstorm

Still, we should not become too pessimistic about the Belgian labour market, certainly not in the somewhat longer term. After all, we also see positive signs. For instance, the vacancy rate (vacancies as a % of the total labour supply) in the manufacturing industry was already higher at the end of 2020 than before the crisis. In contrast to the service sectors, manufacturing has clearly suffered less from the pandemic. More generally, the tightness on the Belgian labour market, which peaked before the crisis, may return more quickly than expected. This is partly because the working-age population will start to fall from 2021 onwards, in turn a consequence of baby boomers retiring. At the same time, there are still many bottleneck professions (technicians, nurses, etc.).

To the extent that the education, skills and interest of the redundant workers from the sectors affected by covid-19 do not match the available labour demand, the labour market mismatch risks becoming an even greater problem. Therefore, labour supply flexibility (retraining, smooth transition to other jobs or sectors, etc.) will prove more important than ever for a healthy labour market recovery in the post-corona period. Labour market policy will have to ensure that the recovery of economic growth is not hindered by a lack of the right employees. First, traditional policy calls for intensified activation and guidance of the unemployed and inactive. Second, new reforms are needed to cure the Belgian labour market of its structural ailments (including insufficiently flexible work organisation, strict labour legislation, rigid wage-setting institutions and the still high tax burden of labour). Based on the coalition agreements of the various governments, too few reforms are in the pipeline to fundamentally tackle these ills.

To facilitate recovery, the temporary unemployment system also needs to be reviewed. In the short term, as an automatic stabiliser, it is efficient and necessary to cushion the initial shock of an economic crisis. But as the term suggests, its use must be temporary. After all, the system is a passive, non-future-oriented support that may hamper the rapid reintegration of those concerned into the labour market. There is a risk that staying in the system for too long will lock them in and doom them to effective unemployment.

As such, it is important to create a good profile of who is in the system. For temporarily unemployed people whose re-employment in their former job has become doubtful, a training offensive or temporary secondment (e.g. in the care sector) may be useful to encourage a reorientation. This should avoid that workers who are needed elsewhere in the economy would remain blocked in temporary unemployment. Furthermore, the question remains whether a system of temporary unemployment is always the ideal solution to absorb short-term shocks. In some cases, it may be better to provide companies with a wage subsidy (as happens in many other European countries) and thus keep employees on board. This is, for example, the case for companies that still have work but temporarily no income (e.g. travel agencies that have to rebook holidays at a later date) or that would like to provide retraining for temporary surplus staff themselves.

To avoid massive job losses, the right environment must be created for viable businesses to survive. But at the same time, we must not forget that the economy is a dynamic entity with constant creation and destruction of activities and jobs. Rather than fiercely protecting certain jobs in certain companies, it is therefore desirable to protect the employees themselves by enabling them to respond flexibly to new career opportunities. This requires constant efforts in terms of further training and retraining in response to the (changing) needs of the economy. A strong commitment to this will certainly limit the longer-term consequences of the pandemic for the labour market.