The voluntary carbon market needs a dose of regulation

The verdict is clear; the world is still far from a path that would successfully limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. Getting on that path requires a substantial reduction in GHG emissions already by 2030 on the way to net-zero by 20501. While national pledges and targets to reach net-zero now cover three-quarters of global emissions, according to the UN, the world is still on track to see a 10% increase in emissions by 2030 compared to 20102. While stronger commitments from governments are crucial to reaching climate targets, private sector participation is key as well. One tool for pulling in more participants from the private sector is the market for carbon offset credits, known as the voluntary carbon market (VCM). The VCM is not without its critics, however, especially given a lack of regulation and subsequent concerns about greenwashing. A new proposal from the US to establish a program that mirrors the VCM in many ways, with the private sector purchasing credits to help fund the energy transition in developing economies, could go a long way toward introducing regulatory scrutiny into the VCM. Such scrutiny is badly needed if the market is to flourish and become a truly significant tool in paving the way toward net-zero.

2 https://unfccc.int/ndc-synthesis-report-2022#Projected-GHG-Emission-levels

A tool for businesses with climate potential

The VCM is meant to support two different but complementary aims: help businesses (or other entities) fulfil climate goals while also unlocking private sector funding for much needed transition projects. To this end, the VCM is essentially a market for carbon offsets. Projects that reduce or remove emissions from the atmosphere are registered (by private registries) and sold as credits to businesses that can then use those credits to offset their remaining emissions—that is to say, emissions remaining after significant efforts have already been made by the business to reduce their starting carbon footprint. These projects can range from things like renewable energy investments or outfitting communities with more efficient lighting (emission reduction), to the protection of natural carbon sinks or investments in carbon capture technologies (emission removal).

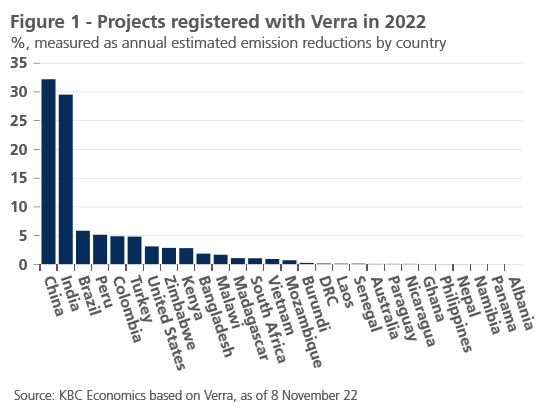

Private sector participants may have many reasons for participating in the VCM, whether due to net-zero pledges, reputational interests, stakeholder demand, or an eye toward future potential regulation and the future operational disruptions that a changing climate could cause. Furthermore, private sector participation on the path to net-zero is vital given the scale of the needed transition. Not only does the VCM support this participation, but it can also help channel funding to developing economies, as that is where the majority of the carbon offset projects are located (figure 1).

But regulation is lacking

The VCM is distinct from compliance-based carbon markets, such as the EU ETS, in a number of ways. The first distinction is in the name itself; participants in the VCM are there voluntarily, whereas businesses within the sectors covered by the EU ETS are under regulatory requirements to participate. Second, the markets function in separate ways, with the EU ETS being a cap-and-trade system, where regulators set the total allotted emissions. This allows for a single, market-determined price based on demand. In the VCM, on the contrary, there is no one-stop shop for carbon credits, and the fragmented nature of the market means that the price for one credit (which equals one ton of GHG emissions) can vary depending on the type of project behind the credit, its geography, its permanence (the risk that reductions or removals could be reversed), and whether there are other sustainable development goals supported by the project. Finally, whereas compliance markets are by nature regulated, the VCM currently lacks regulatory oversight.

A lack of regulation rightfully gives rise to important concerns about the overall quality and scalability of the market. The main concern is that the VCM could allow for greenwashing by businesses as they tout their climate credentials. This is because some might lean on carbon offsets to avoid first prioritizing the reduction of their own emission footprint. Furthermore, a lack of regulation makes it difficult to verify if the project associated with the purchased credit delivers on its promised reduction or removal.

There is, however, an effort to introduce global standardized benchmarks that can be applied to the carbon crediting programs of private registries to mitigate these problems. The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM), e.g., was born out of an initiative led by Mark Carney as UN special envoy for climate action and finance. The ICVM is currently working on a set of ten Core Carbon Principles that would form the basis for such benchmarking. These principles include concepts like additionality — requiring that the removals or reductions from a project be something that wouldn’t have occurred without the incentive created (i.e., revenues made) by registering the activity as a carbon credit — no double counting, strong program governance, and permanence (non-permanent reductions or removals within a sufficiently long horizon, possibly 100 years, need to be compensated). These core principles are not without criticism, however, as some argue they are too strict and would reduce the universe of acceptable credits by too much. And because the ICVCM is not a regulatory body, it remains to be seen if these standards will be adopted by the industry.

True regulatory oversight, therefore, would be a positive development for the market. It would help increase trust in the VCM and, subsequently, participation. In this light, a new proposal put forth by John Kerry in his role as US climate envoy may have important implications for the VCM. The program, dubbed the Energy Transition Accelerator, would have governments that reduce emissions from their power systems (think of emerging markets that still rely heavily on coal for electricity generation) turn these reductions into credits that can be purchased by the private sector as offsets. No double counting, however, requires that any credits sold cannot come from reductions that count towards a country’s climate targets (Nationally Determined Contributions). Cooperation at the international level on such a program would seemingly necessitate some regulatory oversight. Whether that regulatory oversight picks up, e.g., the Core Carbon Principles of the ICVCM, or if it uses another set of standards and benchmarks, the principles used by the Energy Transition Accelerator can provide a roadmap for the VCM. The announcement itself mentioned restrictions such as purchasing companies needing to have net-zero goals and science-based interim targets, and that they only use these credits as supplements, rather than substitutes, for emission reductions3.

If the voluntary carbon market is to live up to its potential as a tool to accelerate and support the climate transition, trust in the market itself is a prerequisite. Establishing and protecting that trust is difficult without regulatory oversight. As such, participants in the VCM should welcome regulatory intervention, and potentially look toward programs like the Energy Transition Accelerator as a guideline in building up the integrity of the market.