The transition to a more circular economy

- 1. Concept and framework

- 2. Opportunities but also obstacles

- 3. A state of affairs

- 4. Role of government

- 5. Concluding remarks

Read publication below or click here for PDF

The growing world population combined with increasing prosperity in large parts of the world is putting increasing pressure on our planet. The problem is strongly related to the prevailing "linear" economic model. This makes that depletion and squander of natural resources, as well as waste production and environmental pollution, are widespread and increasing today. Over the past decade, the discussion around sustainability has taken a new turn with the "circular economy”. In this model, products and raw materials are maximally reused and value destruction is minimized. In practice, this means closing as many cycles as possible in economic processes. The circular approach also focuses heavily on the provision of services rather than products ("performance economy") and on the optimal use of products through exchange between users ("sharing economy").

There are economic opportunities in the circular approach. It offers companies opportunities to save costs, be less dependent on raw material imports from often unstable countries and distinguish themselves with a new value proposition. What the final economic potential will be nevertheless remains very uncertain, as circularity is accompanied by derived, dynamic effects. As products last longer and are reused and shared more often, the total number of goods produced decreases. This is offset by material efficiency and increased use, maintenance and repair services. The ultimate impact of the transition to a circular economy on GDP is thus unclear a priori. Moreover, in a dynamic economy, production factors released as a result of less production will find their way elsewhere into new activity. It is then necessary to be careful that the final consumption of raw materials does not increase again.

Meanwhile, the circular economy is gaining in importance, certainly also in Belgium, although the linear economy remains by far the dominant model. Our country can boast a great deal of circular expertise and is already among the top European countries in terms of recycling and circular material consumption. However, this is offset by a significant material footprint and even a very high dependence on the import of materials. So there is still room for improvement in these areas. From a broader perspective, many promising, spontaneous initiatives towards a circular economy exist in Belgium. In many cases, however, these are small niche projects (which in addition to reducing and reusing materials also focus on product repair, rental and share activities, etc.) and there is still a long way to go to scale them up to mainstream practice.

This research report consists of five sections. Section 1 discusses the concept of circularity and frames it within related schools of thought. Section 2 provides an overview of the economic opportunities contained in the shift to a circular economy, but also points out the many obstacles that remain. Section 3 provides a current state of affairs regarding the extent to which the circular economy is now gaining a foothold. The focus here is both global and specifically on Belgium. Section 4 discusses the role of government, with a rough overview of policy plans and actions at the European level and in Belgium. In Section 5 we formulate some concluding remarks.

1. Concept and framework

From a linear economy...

Since the start of the industrial revolution some two and a half centuries ago, the world economy has experienced substantial growth. Technological innovation but also the availability of cheap and seemingly unlimited amounts of natural resources (fossil fuels, metals and minerals) contributed to this. Growth brought ever higher levels of prosperity and consumption in large parts of the world. The flip side is that depletion, waste and pollution are today widespread and affecting the environment, with damage that is often irreparable or in danger of becoming so (e.g., deforestation and loss of biodiversity).1 The main cause is that most companies still operate (mainly) in traditional production chains, where raw materials are converted into products that become waste at the end of their useful life.

This "linear economy," sometimes called the "disposable economy," is characterised by the three-pronged take (mine raw materials), make (produce goods) and waste (dispose of waste). Linear business models aim to sell as many products as possible at the lowest possible cost. That these are often of inferior quality and have a limited lifespan contributes to the disposable culture. Once in use, the value of products usually decreases until they become waste and have a negative value: you have to pay for them to get rid of them. With that, valuable resources are lost and new ones have to be mined, which depletes the earth. Dumping also causes ecological damage (e.g. large amounts of plastic in the oceans), while the CO2 emissions associated with the destruction contribute to global warming.

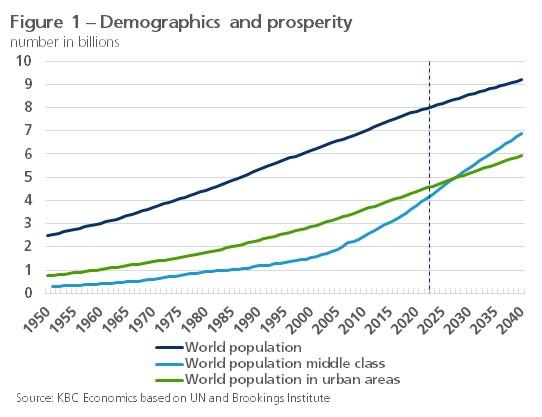

In the coming decades, the world population will continue to increase, from 8 billion today to 9.7 billion in 2050, with an increasing proportion living in cities and joining the middle class (see Figure 1).2 Assuming the linear model, waste generation will continue to rise substantially as a result. According to a recent United Nations analysis, if no drastic action is taken, the amount of municipal solid waste (i.e., not taking into account industrial waste) worldwide would increase from 2.2 billion tons in 2020 to 3.8 billion tons in 2050, an increase of as much as 78%.3 Almost one-third of that increase is due to projected growth in the world's population and over two-thirds to projected growth in world GDP.

Consumption of natural resources will also continue to grow briskly. On the one hand, decarbonization (i.e., the replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy) will indeed dampen consumption of oil and gas, among other things. But on the other hand, the energy transition will be accompanied by a sharp increase in demand for metals and minerals (copper, silver, nickel, lithium...).4 Also, the (better and more sustainable) housing and mobility of the further growing world population will increase the demand for raw materials (e.g. steel and cement). According to an OECD estimate, between 2018 and 2060, global raw material demand would almost double from 89 to 167 billion tons.5 This has several implications. First, the resources in question (with the exception of renewable energy) are in limited supply. Second, the extraction and processing of raw materials leads to large environmental pressures and climate change. Third, certain raw materials can only be extracted in a limited number of countries, which can create resource dependence and geopolitical tensions.

...towards a circular economy

Since the 1970s, people have been thinking about how to deal with depletion and waste problems. Back then, the Club of Rome report on the limits to growth especially caused a stir.6 More recently, the idea is gaining ground that economic growth is still compatible with ecological balance but requires a U-turn in the way growth is achieved. Specific attention is given to the so-called "circular economy", as opposed to the "linear economy". This is an economic system that aims to reuse products and raw materials as much as possible and destroy as little value as possible.

A circular system has two material cycles: a biological cycle, in which residues are safely returned to nature after use, and a technical cycle, in which products or components are designed and marketed in such a way that they can be reused in a high-quality manner. The system is thus ecologically and economically "restorative”. The biological cycle implies the maximum use of pure, non-toxic materials. The technical cycle assumes that products can be easily maintained, repaired or refurbished to extend their useful life. This can lead to reuse by a new consumer (second life). At the end of life, components or materials should be easily disassembled, reclaimed and redirected into new products. Thus, the system is also "regenerative," i.e., self-renewing. Systems thinking is an important principle behind the circular economy. This means thinking about the life cycle (including the end of life) of products right from the design stage in order to make closed cycles possible.

Note that the circular economy is more than recycling. Recycling reuses residual or waste materials, but usually in a low-quality manner and only at the end of the life cycle of products. Usually there is quality loss of reclaimed materials, which limits reusability. Product idea, design and technical specifications are also lost during recycling. This is why people often talk about downcycling instead of recycling (e.g., use packaging waste to produce street furniture). The circular economy focuses on preserving value by first maintaining products and, if necessary, repairing or upgrading them so that they last longer (upcycling), then reusing parts and finally reusing the materials contained in them. Recycling is only a final option to close the loop. The goal of considering products as valuable for a longer time is embodied in the so-called R-strategies: Refuse, Rethink, Reduce, Reuse, Repair, Refurbish, Remanufacture, Repurpose, Recover, Recycle.

Related schools of thought

The circular economy grew into a new buzz word in recent years. However, the idea of adopting the closing of cycles inherent in natural ecosystems as a model for a more natural ordering of the economy is not new and was launched by American Barry Commoner at the beginning of the 1970s.7 The idea of extending the life span of products through reuse and recycling was first developed by the Swiss Walter Stahel.8 He is the man behind the “cradle to cradle” philosophy, which was later further developed by William McDonough and Michael Braungarten.9 The central idea, which is also reflected in the circular economy, is that materials are put to useful use in another product after their life in one product. It opposes the “cradle to grave” philosophy in the classical linear economy.

Sometimes the concepts "circular economy" and "sustainable economy" are used in the same breath, as if they were (almost) synonyms. This is not quite right, because economic cycles can be closed in non-sustainable ways if necessary. For example, recycling can be done in an energy-intensive or polluting way. A lot of recycling companies also cause odor or noise pollution to local residents. Also, the practice of shipping electronic waste to developing countries for recycling not infrequently has negative consequences for people and the environment locally. More generally, the idea of the circular economy, at least in its purest form, focuses on ecological aspects and disregards the social dimension, which also prevails in sustainability (human rights, working conditions, etc.).

Nevertheless, the link is often made between the circular economy and a so-called "collaborative economy”. Circular solutions that simultaneously opt for collaboration and promote community building are more sustainable. The circle then not only indicates the closing of physical cycles, but also symbolises new forms of communal action. Indeed, to make a circular economy work, new forms of coordination and cooperation are needed. For this, a company that wants to offer a circular product depends on the willingness of suppliers to also incorporate the philosophy of the circular economy into their operations.

The interaction between producer and consumer is also intensifying, as companies in the circular economy are increasingly providing a service rather than a product. The latter is known as the "performance economy”. This means that products themselves and the raw materials contained in them remain the property of companies and customers pay for their use, not their possession (e.g., a company selling light instead of bulbs). The "sharing economy” (sometimes also named “we economy") also fits into the circular approach. Instead of everyone purchasing individually, products are used optimally through erasure between users. Unused capacity (idle cars, tools...) is used to maximize product performance. Not only shared use, but also designing and making products together ("co-creation") can contribute to using resources more efficiently and keeping distribution chains as small as possible.

2. Opportunities but also obstacles

Economic opportunity

There are several reasons to make the transition to a circular economy. There is not only the enormous ecological pressure due to an increasing need from the availability of natural resources, which are also increasingly needed to achieve climate goals (think of the use of batteries). There are also many economic opportunities contained in the circular approach and, conversely, continuing with the linear model entails economic risks.

The circular economy offers companies opportunities to save costs through lower resource and material use, waste reduction and less transportation by organizing flows more efficiently. Companies can also become less dependent on raw material and material imports from often unstable countries. Today, Europe is at least 75% dependent on imports from outside the Union for 21 critical raw materials.10 For 14 of those materials it is even (close to) 100%. This dependence implies significant risks in terms of supply and price developments. Access to raw materials may become less predictable in the coming decades as a result of geopolitical tensions and/or as emerging countries take an increasing share. Apart from supply uncertainty, this may also lead to more volatile prices.

Another advantage is that companies can differentiate themselves in the circular economy with a new value proposition. Citizens are increasingly embracing a sustainability mindset, in which circular thinking is at the forefront. New revenue models based on use rather than ownership of goods also enable companies to build more intense, long-term relationships with customers. They contribute to a better knowledge of customers and their changing needs, which facilitates the implementation of a customer centric policy. The customers themselves can also benefit. After all, they are no longer responsible for the maintenance and repair of products or for the latest technological updates themselves.

Furthermore, the circular economy can be an engine for product, process and system innovations. By focusing innovation on solutions to major societal problems, economic and social added value go hand in hand. After all, the major societal challenges are also pre-eminently the markets of the future to which companies can respond. These include, for example, mobility problems or challenges related to climate change or healthcare and demographics. A concrete example is the sharp increase in the number of single-person households - a phenomenon that is occurring throughout Europe - which could greatly increase the potential of the sharing economy.11 New technologies (robotisation in recycling processes, predictive maintenance, self-healing materials, etc.) will also accelerate the transition to a more circular economy.

What the final economic potential will be nevertheless remains very uncertain.12 Indeed, the few figures that are available do not generally take into account the derived, dynamic effects of circularity. As products last longer and are reused and shared more often, the total number of goods produced decreases. This is offset by material efficiency and increased use, maintenance and repair services. Thus, the ultimate impact of the transition to a circular economy on gross domestic product (GDP) and employment is unclear a priori. Moreover, in a dynamic economy, production factors released as a result of less production will find their way elsewhere into new activity. It is then necessary to be careful that resource consumption does not increase again in the end and that the benefits of the initial transition to a circular economy are not partially cancelled out.

Still a lot of obstacles

The transition to a circular economy does not happen by itself and is a long and complex process with many obstacles. After all, the linear economy is deeply rooted and strongly based on selling as many new products as possible, not infrequently with a rather short lifespan. Specifically, "path dependence" in particular hinders the circular economy. Past choices have shaped our current institutions, infrastructure and knowledge and exert a lasting influence on future developments.

For example, prevailing accounting rules, legal and regulatory frameworks, etc. are strongly geared to linear thinking. In consumer protection, property rights, product liability and warranty, the sale of a product is often still the starting point. Concepts such as raw materials and waste today have a specific legal or economic meaning that by no means always corresponds to circular thinking and often differs from country to country. What is seen as a raw material in one country can be labelled as waste as soon as it crosses the border. Finally, rigid legal frameworks also create problems (e.g., labour law or taxation) when initiatives in the sharing economy develop into commercial activities.

A specific brake on the circular economy is start-up investments. Models based on the provision of services rather than the sale of products require large working capital, as there is no transfer of product ownership and products therefore constitute an asset position on the company balance sheet. A variety of financing is then often required to have a chance of success (see Box 1). Another financial obstacle is that circular production chains are often even more expensive than linear ones. This is because of higher management and planning costs and because recycled materials are often more expensive than new ones because recycling often still takes place on too small a scale (the latter does disappear, however, as raw materials become more expensive). There is also an uneven playing field in favour of the linear economy. Costs related to waste treatment, soil remediation, health care, etc. are not always (fully) internalized, but (partly) passed on to society.

Operational obstacles also prevent the circular economy from being established quickly. For this, a company that wants to offer a circular product often depends on the willingness and pace at which suppliers also incorporate the circular economy into their operations. Working together within and between production chains to create new circular product combinations requires an industrial symbiosis that is not easy to achieve. The business model in the circular economy that is based more on providing services is also a lot more complex, with major logistical challenges, new pricing mechanisms and managing contracts rather than simply delivering products.

Related to this are technological obstacles. For example, there is a decreasing efficiency of materials reuse. The binding properties of fibrous materials (paper, cotton, etc.) decrease each time recycling is done. So keeping materials in a cycle endlessly without loss of quality is not (always) possible. Moreover, the complexity of newly marketed products increases exponentially: they become smaller and the number of materials used per product increases. This also increases the complexity of recycling processes. Another problem is that reuse and life extension can hinder technological advances. New products usually have new functionalities (e.g., safety features in new cars), so it is not always obvious to keep using old products for a long time.

Finally, there are also sociocultural obstacles. Consumers generally still prefer new products to already used or recycled ones. The latter are often still considered inferior with lower quality or as part of a gray trade circuit. Consumers also still think in terms of products rather than functionalities. Ownership of (many) products gives people a positive feeling. After all, it comes with the enjoyment and freedom to do what one wants with the product (e.g., sell it, pass it on in an inheritance). Moreover, people are status sensitive and goods ownership shows others that "things are going for the better”. Conversely, it is quite possible that consumers in a circular economy would treat products less carefully because they are not their property. As a result, they may break down faster and their lifespan becomes shorter rather than longer.

Box 1 - Financing circular entrepreneurship

Financing innovative business models and technologies is always complex. This is because investments associated with new ideas are often very risky and only pay off in the longer term. In the circular economy, in addition to traditional risks (e.g., the failure of a new idea to catch on with consumers), there are additional risks specifically associated with this new model. Examples include: the greater physical dependency between companies (which creates e.g. a performance risk of suppliers), the drastic change in the cash flow of companies due to new business models, changes in the value of guarantees in new "from possession to use" systems, and the correct assessment of the value of a product given that in circular business models it gets a second life and thus possesses a residual value.

This explains why innovative or fast-growing companies in the circular economy often need additional risk capital in addition to the usual bank credit financing. Business angels, among others, are on the radar: wealthy individuals who, along with their financial contribution, also provide know-how to start-up companies. Private equity is also a form of risk capital in which the investor is actively involved in the company's management. He not only invests himself but, above all, also invests capital raised in funds by private and institutional investors. Venture capital is a special form of private equity, aimed at financing young companies.

When multiple actors invest, the risk is spread. In practice, hybrid financing is often achieved with a package of solutions in which a bank brings together parties from its network to provide parts of the overall financing mix. In addition to its primary role as (partial) financier of circular entrepreneurs, the financial sector can also play a secondary role of network partner and knowledge provider. This includes combining insights into circular business models with knowledge of financial products and risk management. For example, leasing formulas can provide solutions for financing "pay per use" systems in the circular economy.

Financing can be facilitated when risks specific to circular enterprises are mitigated by involving additional parties, such as insurance companies (which can hedge performance risk), factoring companies (which take over receivables from customers) or providers of government guarantees. Furthermore, circular initiatives can also be financially supported (in part) through government grants, at the local level (e.g., in Flanders by VLAIO) or European level (e.g., European Innovation Council, EU-EIC). Often, these apply to smaller projects with funds mainly covering start-up costs for new circular initiatives.

3. A state of affairs

Global perspective

In recent years, the general attention around circularity (in the media, debates, scientific research, etc.) increased substantially, indicating a growing awareness. Yet, at least globally, insufficient progress is being made in the field. According to the Circularity Gap Report 2024, an annual publication by Deloitte and the Circle Economy Foundation, the share of secondary (i.e., recovered) materials as a proportion of all materials used worldwide steadily declined, from 9.1% in 2018 (first measurement) to 7.2% in 2023. This decline occurred against the backdrop of a sharply increased volume of global materials consumption. According to the report, over the six-year period mentioned (2018-2023), that consumption would have amounted to as much as 28% of all materials consumed by humanity since 1900.13

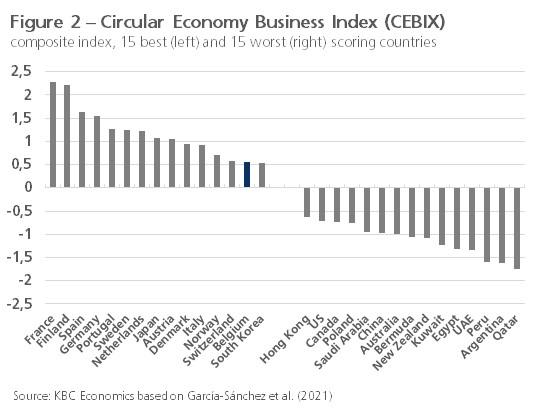

The disappointing result hides the fact that, in terms of tonnage, the amount of secondary materials used worldwide does increase. Moreover, at the country level, there are wide variations in the extent to which the circular economy is now gaining a foothold. A late 2021 study published in the Journal of Environmental Management calculated a Circular Economy Business Index (CEBIX) for a group of 49 countries.14 This is a composite index based on 17 practices companies have implemented to reduce waste generation and improve the reuse of materials and energy. The sample used includes data from some 27,000 companies from 10 sectors in the respective countries over the period 2014-2019. Figure 2 shows the 15 best and 15 worst scoring countries. Most European countries and Japan score relatively well. The US and China are among the group of relatively poor performing countries. Belgium ranks 14th in the country ranking.

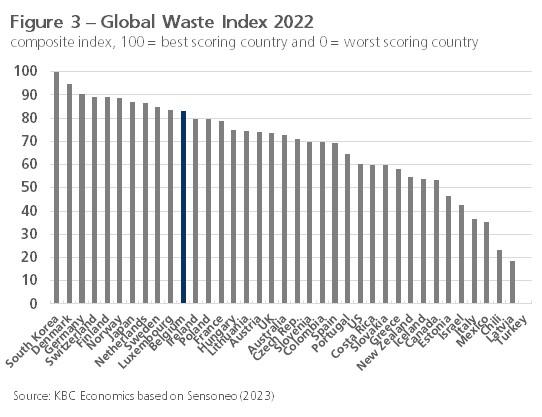

The Global Waste Index is also a composite index that analyses for the 38 OECD countries to what extent they produce waste and how they handle it (landfill, incineration, recycling...). Figure 3 shows the most recent index relating to 2022.15 South Korea, Denmark and Germany are the three best scoring countries. Turkey, Latvia and Chile the three worst scoring countries. Belgium holds 11th place in the ranking of OECD countries. There are countries (e.g. Colombia and Costa Rica) that produce relatively little waste, yet due to its poor treatment, do not achieve a good overall score for the index. Conversely, there are countries (e.g. Denmark and Norway) with relatively high levels of waste that still achieve a good score because of low landfill and incineration.

Belgium in EU perspective

Given its multiple dimensions, it is difficult to capture circularity in a single figure and compare across countries. Measures such as the CEBIX index discussed should thus be interpreted with caution. It is better to look at progress in more detail on a multitude of circular aspects. Useful are the Circular Economy Indicators published by Eurostat for European Union member states (EU27). These are a set of indicators that, while not reflecting the whole complex reality of circularity, still provide a picture of ongoing trends and international differences. In the appendix to this report, we show the indicators concerned in a set of figures. We compare Belgium with three neighbouring countries (the Netherlands, Germany and France) and the EU27. The appendix is divided into three themes: (1) raw materials use and dependence; (2) waste generation and treatment; (3) secondary materials use and wider circularity. Below we discuss the main findings.

Raw material use and dependence.

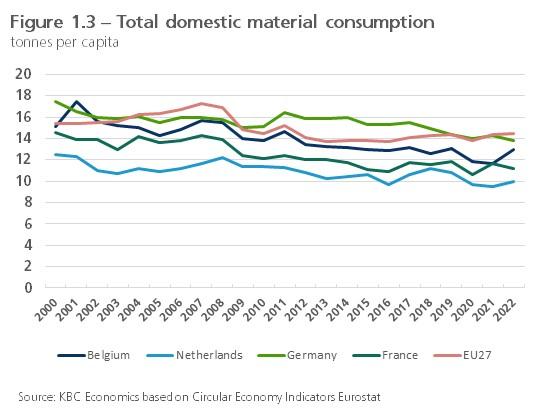

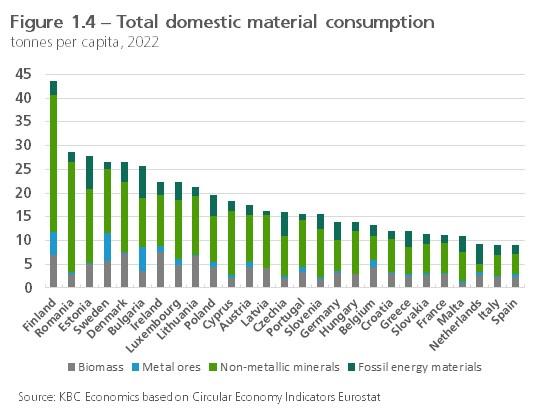

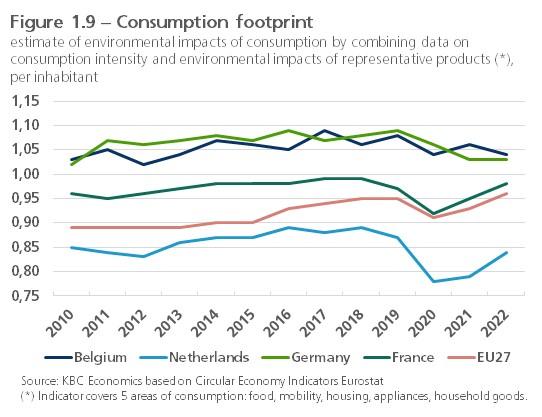

In economies heavily dependent on exports, such as Belgium, a significant portion of the materials input into the economy is destined for abroad. Thus, "direct material input" (expressed per capita) is high in Belgium, above that in neighbouring countries, yet not among the highest in the EU27. The figure remained fairly stable over the past decade. “Domestic material consumption” (i.e. excluding materials incorporated in products that are exported) did decrease and is rather low in Belgium from an EU perspective, although it is lower in France and especially the Netherlands. The "material footprint" reflects the amount of materials needed to produce the goods consumed in the country.16 The indicator takes into account, in the case of imports, foreign material consumption downstream in the production chain. Belgium scores average from an EU perspective and its footprint evolution has remained roughly unchanged over the past decade and a half. That improvement is possible is shown by the comparison with the Netherlands, where the footprint is much lower.

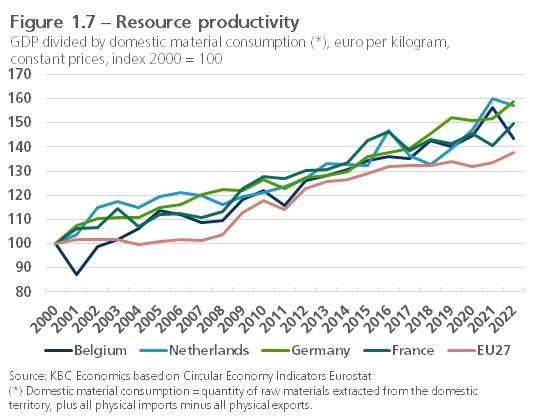

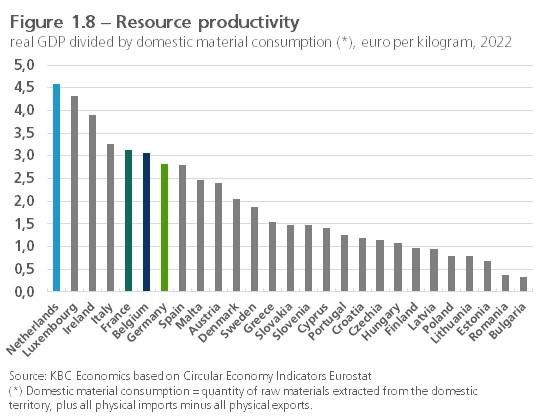

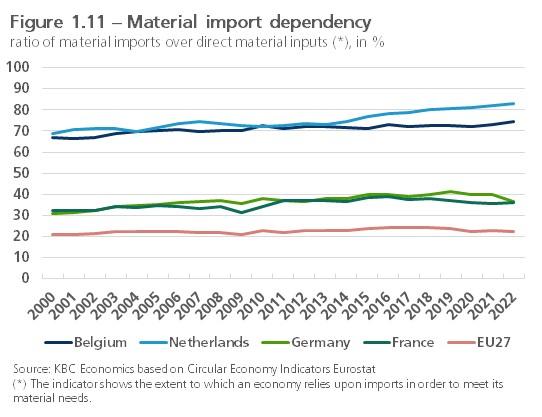

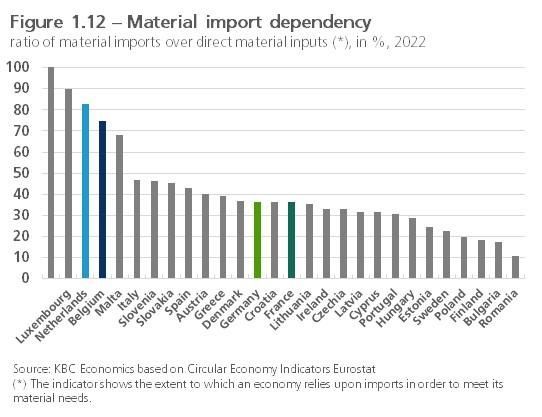

“Resource productivity” relates real GDP to domestic material consumption (i.e., the amount extracted domestically, plus all physical imports minus all physical exports) and measures the extent to which economic activity decouples from materials. The indicator increased in almost all EU countries in recent decades. In Belgium and neighbouring countries, that increase was slightly larger than in the EU as a whole. A nuance is that the trend improvement is partly due to the increasing share in GDP of service sectors, where relatively few materials are used. In terms of the level of resource productivity, the Netherlands again scores particularly well, with the indicator more than twice as high as the EU average. In Belgium, which also scores well, it is one and a half times the EU figure. The materials input into the economy is declining proportionally, but Belgium (also the Netherlands) is heavily and increasingly dependent on imports from abroad for it. That makes the economy very vulnerable to rising prices and supply uncertainty.

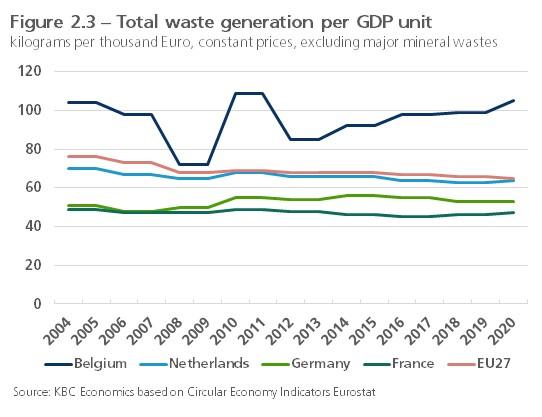

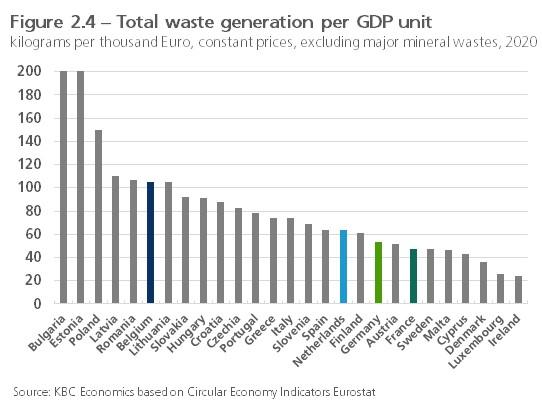

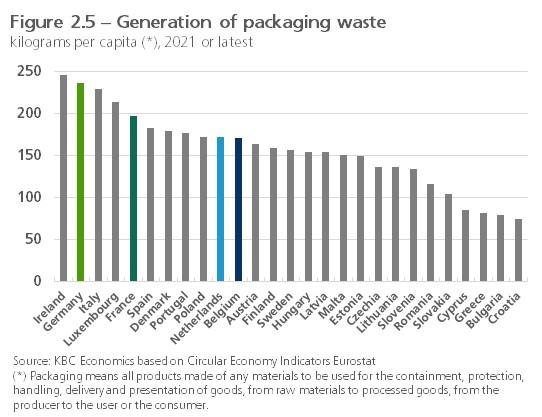

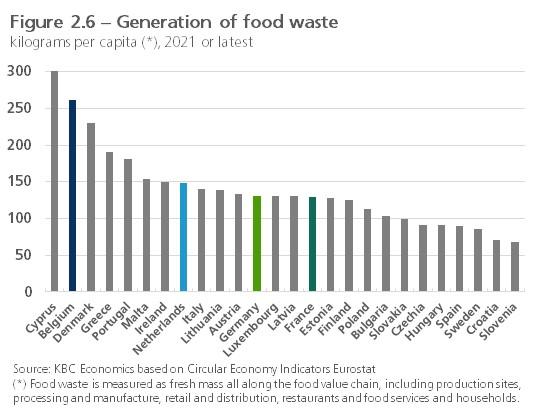

Waste generation and treatment

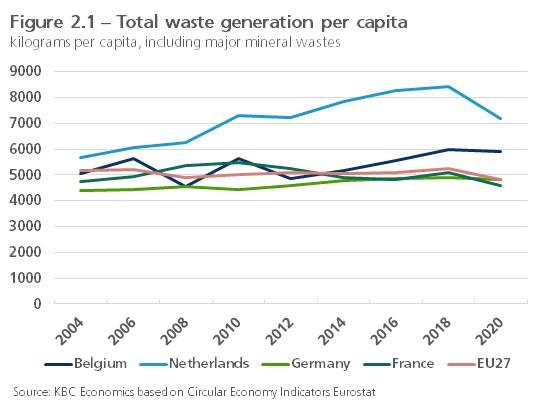

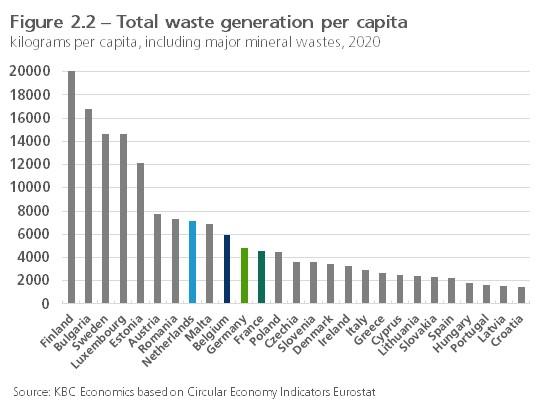

Belgium produces more waste per capita (household, industrial and other) than the EU average, and the amount also increased in recent years. In this category, the Netherlands scores worse, but Germany and France better. Also expressed in relation to economic activity (GDP), waste generation in Belgium is relatively high and increasing. So there is certainly still potential for improvement in waste prevention. A specific problem for Belgium is that, compared to other EU countries, significant food waste is produced. Packaging waste (plastic and other) has also increased in recent years, although Belgium scores rather average here compared to other EU countries.

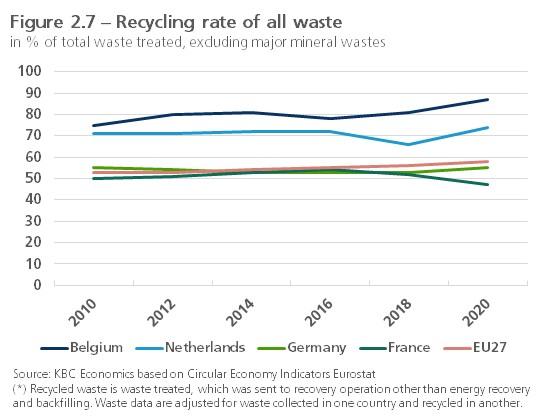

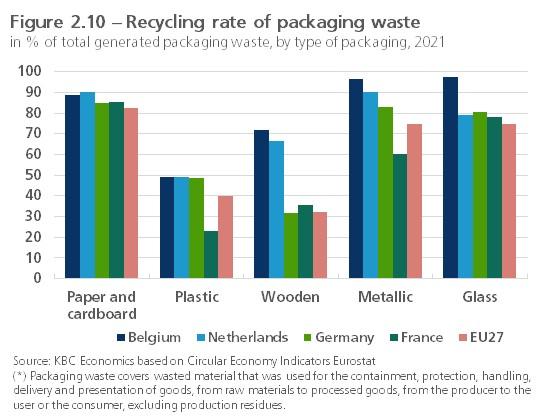

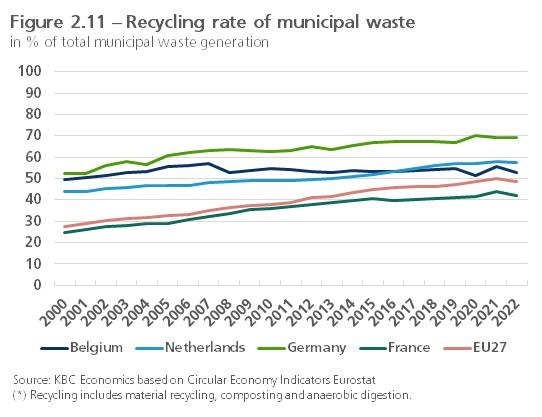

Belgium's relatively poor performance in terms of waste prevention and production is offset by a very high level of recycling. Belgium even leads the EU with the highest recycling rate for all waste produced. The Netherlands also scores well here. Of the waste that is not recycled, only a small fraction is landfilled, the rest is converted into energy through incineration. Specifically for the recycling of municipal waste, Belgium is not doing badly either, although both Germany and the Netherlands perform better. Moreover, recycling has remained rather constant in Belgium over the past decade, while it has increased elsewhere. For packaging waste, Belgium scores relatively well on recycling wooden, metal and glass packaging. Although increasing, there is still much room for improvement, especially for the recycling of plastic packaging, also elsewhere in the EU. Finally, recycling of electrical and electronic waste is strong but declining.

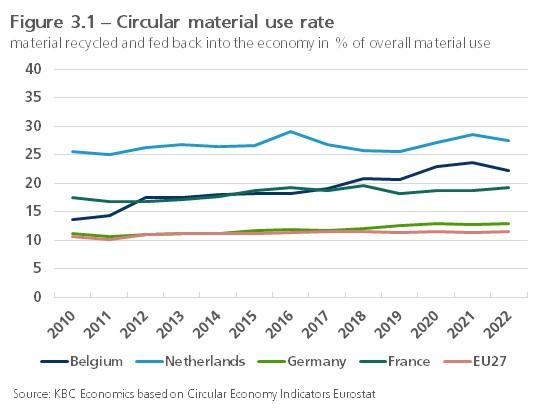

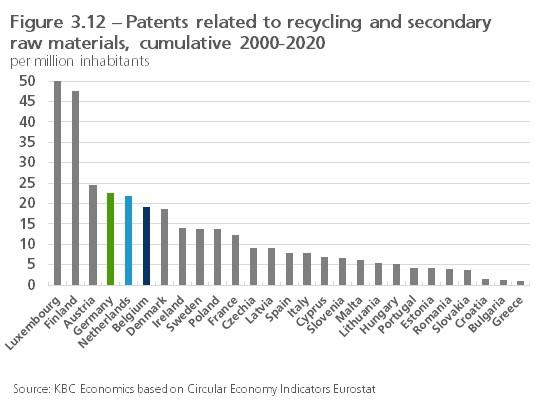

Secondary material use and wider circularity

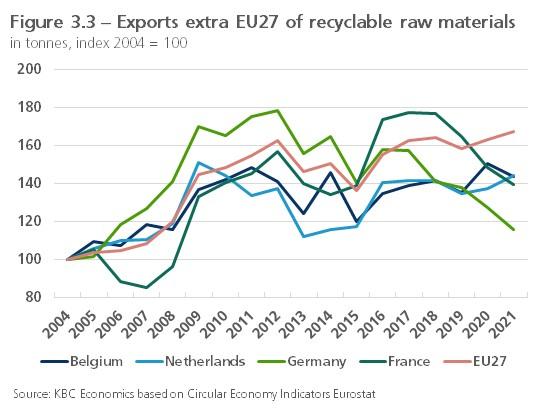

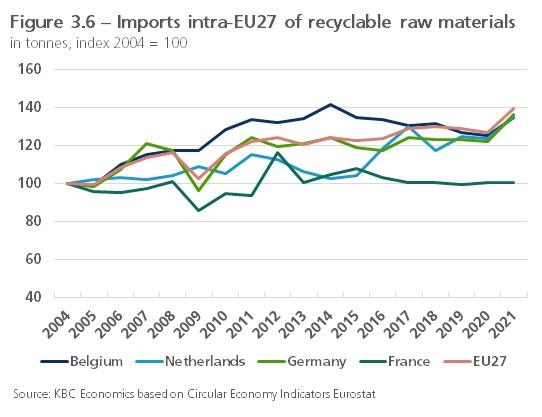

A key indicator of circularity concerns the reuse (secondary use) of recycled materials, expressed as a proportion of total materials consumption in the economy. Belgium performs very well for this “circular material use rate” with the second highest figure (22%) in the EU, after the Netherlands (28%). Its increasing trend indicates that Belgium is becoming increasingly, albeit slowly, circular in terms of materials. EU-wide figures (not available at country level in the Eurostat database) show that reuse varies greatly depending on the nature of the material and is highest for classical materials such as lead and copper. Materials are not always recycled and reused domestically. There is a lively international trade in recyclable materials. The Netherlands leads the EU in both exports and imports (extra EU27). After the Netherlands, Belgium is the largest exporter of recyclable materials, ahead of Germany and France. In terms of their import, Belgium occupies a less prominent position.

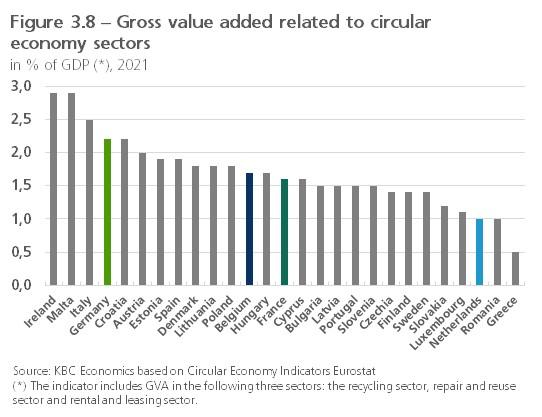

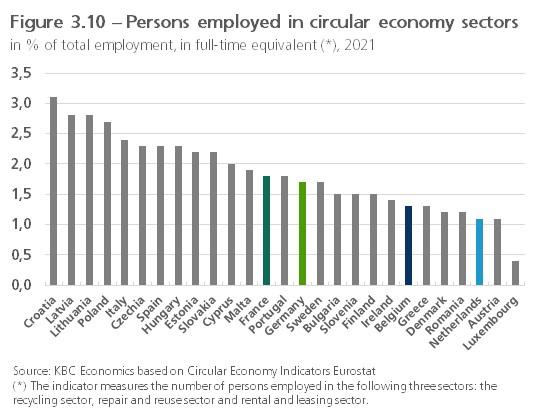

Besides waste collection, recycling, and reuse of materials, the circular economy includes a wide range of other economic activities: maintenance and repair, rental, sharing platforms, second-hand stores.... Which activity very precisely belongs to the circular economy is partly arbitrary and often difficult to capture in a single figure. The Eurostat indicators also include an estimate of the share of "typical" circular sectors in the overall economy. In addition to waste treatment and recycling activities, this includes the maintenance and repair and leasing and rental sectors.17 For the share of these sectors in the total value added in the economy, Belgium scores average from an EU perspective. Their share in total employment is rather low in Belgium. Moreover, for both shares, the Belgian figure remained stable over the past one and a half decade, while there was an increase in the EU as a whole and in Germany in particular. However, the Eurostat approach is crude and in reality, circular activity is undoubtedly higher (see Box 2 for some examples in Belgium). Note also that although Belgium has a mediocre score on the Eurostat estimate, there is relatively high investment in the relevant sectors. Together with Austria, Belgium even ranks first within the EU in this respect.

Box 2 - Examples of circular companies in Belgium

Many Belgian companies today already apply one or more principles of the circular economy. The sectors in which they are active are very diverse and include both (large) established companies as well as young promising companies trying to contribute rather on a small scale, often in a particular niche.

A large part of the already existing circular economy in Belgium relates to waste management and recycling. In terms of waste management, Indaver is a specialist. The company, founded in 1985 by the Public Waste Agency of Flanders (OVAM), is strongly committed to materials recovery. This includes looking at the smallest building blocks (molecules) of waste materials, especially from the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors. In terms of recycling, Umicore and Deceuninck are good examples. Umicore Precious Metals Refining is one of the largest precious metals recycling parks in the world. Deceuninck, producer of PVC plastic profiles, recycles old windows and shutters for incorporation into new window systems. Several companies, including e.g. Group Machiels, are also active in Enhanced Landfill Mining, i.e. the excavation and valorisation of previously dumped waste in landfills. There are also young startups active in waste management. One example is Tictopia, which collects old defective electronic materials, reconditions them and puts them back on the market.

A number of companies are also already successfully applying the strategy of industrial symbiosis. A good example is BASF in Antwerp. The plants there are so interconnected that the end or by-products of one plant form the raw materials or pre-products for other plants, including in other nearby companies (including EuroChem and Air Liquide). In many companies, circular entrepreneurship involves ancillary activities or specific initiatives. For example, retail chain JBC opened its first Repair Corner in 2022, where customers can have broken clothing repaired. Department store chain Colruyt Group has numerous circular projects, including the maximum use of recycled materials for packaging and the application of circular construction methods.

A lot of circular enterprise initiatives in Belgium involve niche activities, often by small young startups. An example of such a company, which received the first Circular Business Award from the Federation of Enterprises in Belgium (FEB) in March 2024, is Juunnoo, a producer of modular, reusable interior walls for buildings. The Silver and Bronze Awards were for Snappies, which offers a b2b service of washable diapers for nurseries, and Out of Use, which proposes sustainable solutions for discarded or unused IT materials. Moreover, through the platform Startit@KBC, in which KBC Group is one of the partners, many new initiatives that fall within the circular economy are supported.1 This is an incubator that supports early-stage, innovative entrepreneurship by providing space, expertise and a network. Table 1 below gives some examples of circular startups that have been or are currently supported by Startit@KBC.

1 See All startups | Start it KBC (startit-x.com).

| Table 1 - Ten examples of circular startups that were/are supported by Startit@KBC | ||||||||||||

| Startup | Activiteit | Website | ||||||||||

| Book in Belgium | Online marketplace for buying and selling used books | www.booksinbelgium.be | ||||||||||

| Carpet of Life | Women in the Moroccan Sahara transform your old wardrobe into a new rug | www.carpetoflife.be | ||||||||||

| From waste to wind | Design and construction of household wind turbines based on recycled plastic | www.fromwastetowind.com | ||||||||||

| Pop'Kidz | Clothing that grows with baby's age | www.pop-kidz.be | ||||||||||

| Green Circle Salons | Recycling of hair waste in hairdressing industry | https://greencirclesalons.eu/ | ||||||||||

| Okret | Take-back and re-commerce systems and consulting for fashion companies | https://okret.be/ | ||||||||||

| Greenzy | Device to easily compost organic waste indoors | https://offre.greenzy.eu/ | ||||||||||

| Noosa | Development of 100% recyclable textile fibers | https://noosafiber.com/ | ||||||||||

| Billie Cup | Drinks in reusable cup | https://billiecup.com/nl/ | ||||||||||

| Sofar | Seats with replaceable and recyclable parts and QR code for lifetime tracking | https://sofar.club/ | ||||||||||

4. Role of government

4. Role of government

Although a lot of circular activities are taking shape, the linear economy remains by far the dominant model. An economy with (almost) fully closed cycles will not be achieved in any near future. That said, an economy with significantly more forms of cycle-closure is possible in time and should be pursued. The potential also depends on the role government plays in enabling and accelerating a circular economy. One requirement is that legislation be aligned with it and harmonised within the EU. Over-regulation should also be avoided. The use of secondary raw materials in new products is still often hampered by environmental, health or product safety regulations. While these usually meet legitimate objectives, their design often does not take into account the efficient use of materials. Furthermore, the government can make an effort to raise awareness. Companies are often unaware of the potential of the circular economy, while consumers are still suspicious of recycled streams and the sharing of goods. Through taxation, the government can help ensure that negative social effects of linear production are transparently reflected in prices. Finally, it can also act as a facilitator, by pooling knowledge or stimulating innovation, and set a good example itself, by introducing the circular idea as much as possible into its own operations and contracts.

At the European level, policy on circularity dates back to 2015, when a first action plan was launched. In March 2020, the European Commission presented a new ambitious plan (Circular Economy Action Plan, CEAP), which is framed within the European Green Deal and aims to (1) promote sustainable product design and production processes, (2) reduce waste and (3) empower consumers, especially by improving access to reliable information on the sustainability of products. The focus is on resource-intensive sectors (electronics, batteries, packaging, plastics, textiles, food, construction). In February 2021, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the action plan, calling for additional measures to achieve a carbon-neutral, environmentally sustainable and fully circular economy by 2050, including stricter recycling rules and binding material use targets by 2030.

Since spring 2022, the Commission proposed a wide range of concrete rules and proposals as part of the CEAP.18 Some telling examples: a ban on the destruction of certain unsold consumer goods, the right of consumers to request a manufacturer to repair a product if this is technically possible, a 12-month extension of the seller's liability after repair, the obligation of a USB-C connector as a universal charging standard, mandatory deposit schemes for plastic bottles and aluminum cans, better consumer protection against misleading green claims.... The initiatives illustrate that European policy on circularity is gradually focusing more on initiatives higher up in the waste hierarchy, including the promotion of product reuse.

In addition, corporate reporting on circularity is also becoming increasingly important in EU regulations. For example, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) lays down guidelines for larger companies on how to integrate sustainability into their business models and manage the external impact of their activities on the environment, people and society. The first reporting is due in 2025 for fiscal year 2024 and includes reporting around resource use and circular economy. A new classification system, called the EU Taxonomy, is being applied within the CSRD to provide companies with a framework and clarity on which activities are considered sustainable. It includes six environmental objectives, one of which is the shift to a circular economy.

At the Belgian level, the government approved the Federal Circular Economy Action Plan at the end of 2021. The plan includes 25 proposals that fall under federal competence and mainly concern product standards and consumer protection. It is intended to complement the actions undertaken by the regions. Cooperation between the federal level and the regions takes place through the Intra-Belgian Platform for Circular Economy (IBPCE).19 The regional plans involve as many social partners as possible (business, finance, social profit, knowledge institutions, etc.) in order to make the necessary circular change through coordinated actions. In Flanders, this partnership bears the name Flanders Circular, which also invests in performance monitoring and research via the Circular Economy Support Centre. On a positive note, more and more efforts are also being made by the business community to chart the progress of circularity in Belgium. The now second Circular Economy Progress Report of the FEB deserves special attention in this regard.20

5. Concluding remarks

Belgium has a great deal of circular expertise and today ranks among the top European countries in terms of recycling and circular use of materials. However, it still has a considerable material footprint and even a very high dependence on the import of materials. There is still work to be done to improve in these areas. From a wider perspective, many promising, spontaneous initiatives towards a circular economy exist in Belgium. However, in many cases, these are small niche projects and there remains a long way to go to scale them up to mainstream practice. Moreover, due to a lack of macro figures on this multitude of initiatives, which are spread across all sectors, it remains difficult to get a good, let alone complete, picture of the extent to which the economy as a whole is evolving towards more circularity. The available figures relate mainly to traditional waste and materials management activities and much less to other circular activities (repair and maintenance, rental and sharing initiatives, etc.).

The success of the transition to a circular economy strongly depends on the extent to which awareness grows that sticking to the current way of linear production and consumption is unsustainable in the long run. This requires not only that non-circular behaviour of companies and citizens be discouraged, but even more so that an environment is created in which circular behaviour becomes easy and logical.21 It is important to ensure that the transition to a circular economy is not at the expense of economic activity and employment, but on the contrary offers new opportunities for growth. After all, economic growth remains essential to cope with other major challenges (think of the aging population). Government policy must therefore focus on the elimination of barriers to circularity. For companies, this also implies improving the general business climate so that new circular entrepreneurship is given every opportunity.

Annex 1. Raw materials use and dependency

Annex 2. Waste generation and treatment

Annex 3. Secondary materials use and wider circularity

1 According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), more than 90% of biodiversity loss is thought to be due to the extraction and processing of natural resources.

2 See, e.g., Kharas (2023), “The rise of the global middle class: how the search for the good life can change the world”, Brookings Institute.

3 UN Environment Programme (2024), “Beyond an age of waste: turning rubbish into a resource”, Global Waste Management Outlook.

4 See, e.g., Watari et al. (2019), “Total material requirement for the global energy transition to 2050”, in Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 148, p. 91-103.

5 OECD (2018), “Global material resources outlook to 2060: economic drivers and environmental consequences”. Note: at the beginning of the 20th century, global resource extraction was only 6 billion tons.

6 According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), more than 90% of biodiversity loss is thought to be due to the extraction and processing of natural resources.

7 Barry Commoner (1971), “The closing circle: nature, man and technology”.

8 Walter Stahel (1982), “The product life factor”.

9 William Mcdonough and Michael Braungarten (2002), “Cradle to cradle: remaking the way we make things”.

10 European Commission (2023), “Study on the critical raw materials for the EU”.

11 See, e.g., Pieter van de Glind (2013), “The consumer potential of collaborative consumption”, University of Utrecht.

12 For an estimate of the circular economy potential in Belgium, see e.g. Theo Geerken et al. (2019), “Assessment of the potential of a circular economy in open economies – Case of Belgium”, Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 227, p. 683-699.

13 Deloitte and Circle Economy Foundation (2024), “The circular economy is gaining popularity, but falling short on action”, The Circularity Gap Report 2024.

14 García-Sánchez et al. (2021), “Which region and which sector leads the circular economy? CEBIX, a multivariant index based on business actions”, Journal of Environmental Management, vol. 297.

15 Sensoneo (2023): Global Waste Index | SENSONEO.

16 Materials, as defined here, consist of four categories: biomass (e.g., wood), fossil (e.g., oil), metals (e.g., iron ore) and minerals (e.g., sand).

17 This delineation of the circular sectors involved based on the system of NACE codes is quite rough. Enterprises may have different economic activities, some of which are circular and some of which are not. Moreover, circular activities may also exist in sectors other than those included here.

18 For a full overview of European policy related to circularity, see Circulaire economie - Consilium (europa.eu). For an evaluation, see Institute for European Environmental Policy (2022), “European circular economy policy landscape overview”.

19 For the federal plan, see Federaal actieplan circulaire economie 2021-2024 | FOD Volksgezondheid (belgium.be). For the regional circularity strategies, see Vlaanderen Circulair - Knooppunt van de circulaire economie in Vlaanderen (vlaanderen-circulair.be), Circular Wallonia (wallonie.be) and be circular be.brussels (circulareconomy.brussels).

20 See Vooruitgangsrapport circulaire economie 2024 - VBO.

21 See, e.g., A. Travaille (2023), “Gedragsstrategie en circulaire economie“, Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat Nederland.

19 Voor het federale plan, zie Actieplan circulaire economie 2021-2024. Voor de regionale strategieën inzake circulariteit, zie Vlaanderen Circulair, Wallonia Circulair en Brussel Circulair.

20 Zie Vooruitgangsrapport circulaire economie 2024 - VBO.

21 Zie bijv. A. Travaille (2023), “Gedragsstrategie en circulaire economie“, Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat Nederland.