The pandemic gives homeworking a boost, but also shows pitfalls

The fight against the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic gives homeworking a new boost. For tasks that do not require physical proximity, working from home is the obvious way to reconcile social distancing with the continuation of economic activity. Meanwhile, the question arises as to how sustainable the coronavirus boost to homeworking will be. After all, in addition to micro and macro-economic advantages, there are also disadvantages, mainly due to the reduced interaction between employees. But if homeworking increases employee satisfaction, it can be a lever for productivity gains. However, successful homeworking also necessitates that basic requirements in terms of ICT infrastructure, digital skills, work organisation and management style are met. And, ultimately, successful homeworking depends on the right balance between working from home and working in the workplace. After all, personal tasks will preferably always take place there.

Coronavirus boost

The fight against the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic puts homeworking back on the agenda. Where possible, homeworking becomes the norm again, like during the lockdown in the first wave, though homeworking has never been absent since then. According to surveys by the Belgian Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG), since the Covid-19 crisis began in Belgium, about 35% of employees have been using homeworking. That share has remained fairly stable since the spring lockdown. Although the share of full-time homeworkers had fallen to less than 10% by mid-September, more than a quarter of the employees then combined working from home with working at the workplace.

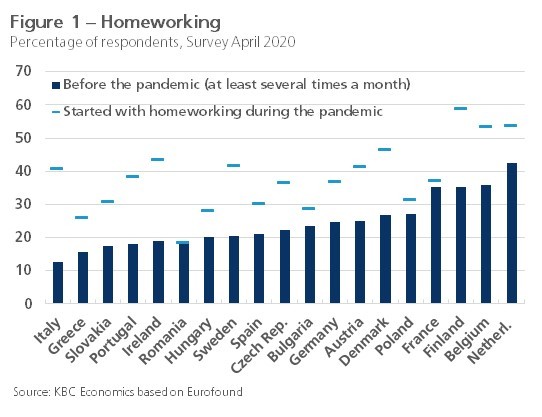

Figure 1 shows that homeworking was more or less widespread in almost all European countries even before the Covid-19 crisis. As a result of the crisis, homeworking has increased significantly everywhere. This is logical, because for activities that do not require physical proximity, homeworking is the obvious way to reconcile social distancing with the continuation of economic activity. Meanwhile, the question arises as to how sustainable the coronavirus boost to homeworking will be. In the ERMG surveys, one in three companies say they will use teleworking more extensively after the crisis than before. A recent survey by the HR services group Acerta, KU Leuven and the HR Square network platform also points to the significantly increased popularity of homeworking.

Of course, it will not be possible to do every job from home. Research (OECD, 2020) for European countries shows that before the crisis, knowledge-intensive jobs in service sectors were mainly eligible, while homeworking is less common in manufacturing and less knowledge-intensive service sectors. The ERMG figures on homeworking during the crisis in Belgium confirm this picture. However, further digitisation may increase the possibilities to work from home. And a greatly expanded application of homeworking can have significant economic consequences, both macro-economic and micro-economic, for the companies and workers involved.nemers.

Advantages and disadvantages

Homeworking offers advantages and disadvantages and the balance is difficult to assess a priori. One advantage is that commuting between home and work is no longer necessary. This not only saves time, but also shortens traffic jams and benefits the environment. Homeworking can reduce geographical obstacles on the labour market. This can make jobs more accessible to more people and help raise the employment rate. As a result of the larger recruitment pool, scarcity is less likely to drive up labour costs and employers can more easily find an employee with the right profile. In this way, homeworking can help alleviate the qualitative mismatch on the labour market.

But homeworking has an important, potentially negative impact on workplace organisation. It threatens to reduce the interaction between employees, and that could weigh on company performance. Not only does the spontaneous exchange of experiences at the coffee machine decrease, but homeworking also makes knowledge transfer to new employees more difficult and stifles spontaneous cross-fertilisation and learning in the workplace. This is bad for the collective accumulation of knowledge and can undermine the organisation’s capacity for innovation and productivity.

The OECD (2020) highlights the crucial role of employee satisfaction for productivity. The impact of homeworking on employee satisfaction is not unambiguous. In principle, homeworking facilitates the balance between professional and family duties. However, the vaguer demarcation of working hours can also lead to overtime being concealed. And without a good home office, homeworking causes dissatisfaction. Homeworking reduces social contacts and can lead to loneliness and alienation of the employee.

However, if homeworking increases employee satisfaction, it can be a lever for productivity gains. Satisfied employees can be more focused on their job from home, which can benefit their productivity. An experiment with call centre employees at a large Chinese listed travel agency, in which randomly selected employees could voluntarily work from home, showed a 13% increase in productivity due to working from home (N. Bloom, 2015). In addition, employee satisfaction rose, absenteeism fell, the severance ratio halved and, perhaps counterintuitively, performance-related promotions fell. Satisfied employees therefore also yield savings for a company. They are generally more loyal, and this helps to control labour costs because more loyal employees may lower financial demands, while lower staff turnover reduces recruitment costs.

Conditions and balance

The impact of homeworking on an employee’s satisfaction often depends on their individual preferences. Therefore, some freedom of choice is important. Forced homeworking in the Covid-19 crisis highlights the advantages as well as the disadvantages. All tasks, including those that are less suitable, have to be done from home, sometimes in poor conditions, for example due to the presence of children who cannot attend school or due to the lack of a suitable home workplace. This situation must be maintained for a long time without physical contact with colleagues.

The OECD (2020) points to even more basic conditions for successful homeworking. An adequate ICT infrastructure and digitally skilled staff are of course indispensable. In the work organisation, explicit time should be spent on building up and sharing knowledge and experience. Working from home is not in line with a traditional approach to management and supervision, which is based on monitoring the presence and activities of employees. It requires a relationship of trust between manager and employee, in which evaluations are based more on results. The introduction of such management practices, including homeworking, in German companies had a positive effect on product improvements and process innovation (O. N. Godart, et al., 2016). However, it is difficult to find out what is the decisive factor, because management style and homeworking go hand in hand.

In the end, the result depends on finding the right balance between working from home and working on the work floor. This differs depending on the job. 100% homeworking probably remains the exception. In the survey mentioned above (Acerta, etc.), only 15% of companies expect not to need office space in the future. More than half will still need the same amount of office space or more. After all, personal tasks will always preferably continue to take place on the work floor.n taken zullen altijd bij voorkeur op de werkvloer blijven gebeuren.