The gender wage gap: sticky and complex

The difference between the average gross hourly wages of women and men, the so-called gender wage gap, is a persistent phenomenon that is highlighted several times each year. The causes are of all kinds and it is often difficult to distinguish between intrinsically personal choices and socially driven norms and beliefs. Because of this complexity, a ready-made solution is far from obvious. But without any effort, the gender pay gap is unlikely to disappear.

Persistent phenomenon

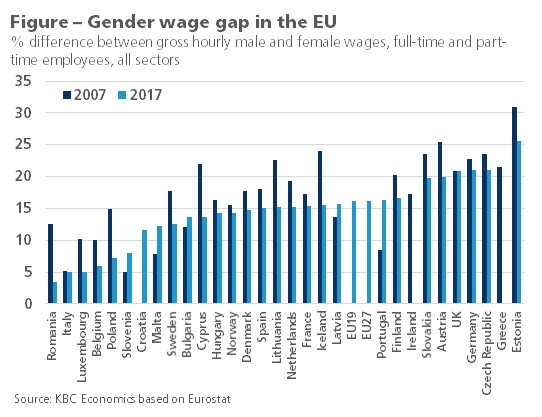

With International Women’s Day ahead (8 March), the gender wage gap is always a hot topic. The gender pay gap is defined as the difference between the average gross hourly earnings of women and men, usually expressed as a percentage of the average male earnings. The subject returns annually in news items etc. because it is a persistent phenomenon that has only evolved to a limited extent over the years. According to Eurostat figures, the average gender pay gap for the European Union in 2017 was 16.1%. In other words, women earned an average of only 84 cents for every euro a man earned in 2017. Hence, in 2017, women worked for free for about 2 months compared to men. In 2010, the pay gap was 17.1%. The decline over the past 10 years was therefore rather limited.

Within the EU, there are considerable differences between countries. Estonia, Greece and the Czech Republic are at the top of the rankings. Romania, Italy and Luxembourg have the lowest gender pay gap. It is important to note that the indicator shown is not a perfect reflection of overall inequality in the labour market between men and women. In countries where female labour market participation is low, the gender pay gap is also generally lower. This is the case for Romania and Italy, for example. The figure also shows that for most EU countries the gender pay gap has narrowed over the last decade, although the extent of this gap varies greatly between countries.

Different causes

There is an extensive literature on the different causes of the gender wage gap. An important factor is the overrepresentation of women in sectors where wages are relatively low, such as (health) care and education. Female preferences for the ‘softer’ sectors are likely to play a role in this, but studies show that choices for certain occupations are also largely socially constructed. Initiatives to break stereotypes and encourage girls to choose a course in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) or ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) are trying to change this.

In addition, although the average level of education of women in many countries is higher than that of male workers, women still earn less, regardless of the sector in which they are active. Here, too, social trends are probably at the base of the issue. Some studies even show that both men and women consider the work done by men to be more valuable as a result of ingrained unequal gender standards.

An additional element is that women are strongly under-represented in management positions and, therefore, in well-paid jobs. In Belgium, for example, women make up 50% of the bottom one percent of wage earners, but only 26% of the top one percent. Opportunities to climb the hierarchical ladder within companies vary between sectors, but overall, women tend to progress much less to a top position. Within the EU, for example, managers are twice as often male. Discrimination, but also personal choices play a role in this. The latter may also be socially driven.

In addition, parenthood and family composition play a role in the gender wage gap. After all, empirical research shows that parenthood on average leads to a decrease in pay for women - the so-called punishment for motherhood - while for men it causes a (limited) wage increase - the bonus for fatherhood. The family pay gaps are a major contributor to the gender pay gap, particularly in Eastern Europe1. But these forces are also at work in Northern and Central Europe. Related to this is the fact that women often take on more unpaid work (household chores, caring for children and other family members...) and, as a result, more often work part-time. Related to this, women tend to take more career breaks than men, e.g. parental or care leave.

The other way around in the future?

In addition to the above list, there are undoubtedly other factors influencing the gender wage gap. Regardless of the exact cause, policies can have a significant impact on the narrowing of the gap. Legal provisions prohibiting gender-based discrimination in the workplace and their enforcement are a first step. Sufficient access to childcare, flexible working hours and a more equal distribution of parental leave between both parents also contribute to reducing the gender pay gap. Policies can also help to reduce the gender pay gap in terms of adjusting social norms, gender stereotypes and social perceptions of the roles of men and women, which are often deeply rooted. Personal choices that are (un)consciously socially driven can also evolve towards more equality between men and women on the labour market.

Still, it’s yet unclear whether the gender pay gap will ever completely disappear or even turn to women’s advantage. There is no doubt that the aim must be to eradicate discrimination based on sex. However, men and women remain different, even if only in biological terms. If these inherent differences are at the root of individual preferences that lead to different study and career choices, the complete elimination of the gender wage gap may not be feasible or even desirable. Moreover, the way in which the gender pay gap is measured is an important factor in the debate. A macro-economic approach such as the one above always gives a bias because you cannot check sufficiently for alternative explanations. By looking at pay differences for specific jobs within specific sectors - an approach at the micro level - factors such as ‘less ambition’ or ‘other goals’ among women can be refuted.

In any case, the gender pay gap remains a complex phenomenon. Without any efforts, it probably won’t disappear.

1 Source: E. Cukrowska-Torzewska and A. Lovasz (2019), The role of parenthood in shaping the gender wage gap – A comparative analysis of 26 European countries