The future of carbon pricing: a primer for businesses

The authors would like to thank KBC Group Corporate Sustainability and Jonas Schroyens for their valued inputs.

Content table:

- Introduction

- Emissions reductions: a key pillar of climate policy

- Reducing emissions through carbon pricing

- Carbon pricing in practice

- Higher prices in the (near) future

- Internal carbon pricing

- Conclusion

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Introduction

With governments increasing their commitments to tackle the climate crisis and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the coming years, carbon pricing is expected to become a progressively important pillar of climate policy. Carbon pricing addresses a major market failure in that the high social – and increasingly economic – cost of GHG emissions, including carbon dioxide (CO2), is not properly reflected in market prices. Imposing a market-conforming price on (the costs of) GHG emissions should address this market failure and incentivizes businesses, and potentially also households, to take these social costs into account and reduce emissions, either through innovation and technological switching, or simply through reduced production (or consumption).

While the EU is already a leader in carbon pricing, with the EU emissions trading system (ETS) established in 2005 (and last revised in 2018) covering the most energy-intensive sectors, carbon pricing will likely become an even more prominent tool used in the EU’s climate policy if the goal of becoming climate neutral by 2050 is to be realized. This could play out in a number of ways, including through an expansion of the EU ETS to new sectors, a faster reduction of the emissions permits allocated within the ETS, the introduction of carbon taxes in addition to the ETS, and the possibility to impose carbon border taxes/tariffs to prevent carbon pricing policies from adversely affecting the EU’s competitiveness and to incentivise carbon pricing elsewhere.

The precise EU framework for the future of carbon pricing is yet to be determined, but it is highly likely that price-based measures will play a central role, and consequently that the price of GHG emissions will rise substantially in the coming years. This makes it increasingly important for businesses to understand their own emissions footprint and how the cost of those emissions may change in the near future. For this reason, even businesses outside the sectors covered by the ETS are adopting internal carbon pricing as a tool to assess both cost and risks associated with emissions.

This report is intended to serve as a primer on carbon pricing, including why it is becoming more prevalent, the different ways governments can and do enforce carbon pricing, how carbon pricing might develop in the near future, and the increasing importance of internal carbon pricing for businesses.

Emissions reductions: a key pillar of climate policy

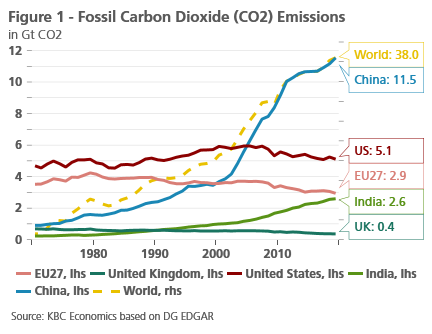

The climate crisis is one of the greatest challenges of our time and cannot be addressed without tackling the rising levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) in our atmosphere. Although anthropogenic CO2 and GHG emissions are widely recognised as one of the most important causes of rising global temperatures, worldwide CO2 emissions are still on an upward path. In 2019, global CO2 emissions rose to 38 gigatonnes, with China, the US and the EU responsible for more than 50% of that total (figure 1). According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global energy-related carbon emissions fell by 5.8% in 2020, thanks to the reduced demand for oil, coal and gas that resulted from the Covid-19 crisis.[1] The 2020 decline is, however, likely to be short-lived, and indeed, monthly emissions have shown an upward trend since May 2020, reflecting in part the stimulus measures funnelled into the global economy to support the recovery. In its latest Global Energy Review, the IEA predicts that energy-related CO2 emissions will rise by 1.5 gigatonnes in 2021, an increase of almost 5%.

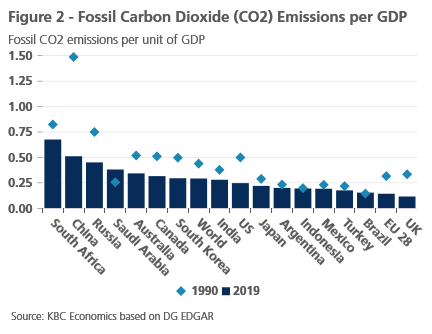

Notable, however, are the different trajectories of CO2-emissions between the three major economies in recent years. While the US has started to roll back its CO2-footprint slightly, and the EU has done so for even longer, China’s emissions are still on an upward path. The divergence is indicative of a global pattern, in which the still-too-slow emission reductions made by advanced economies in recent years have been more than offset by rising emissions in developing and emerging economies. When we consider the GHG intensity of production, we see that like most countries, China’s emissions relative to GDP have decreased since 1990. However, despite (in some cases significant) improvements, the overall emissions intensity of certain economies (particularly South Africa, China and Russia) is still quite high, particularly compared to the EU (figure 2).

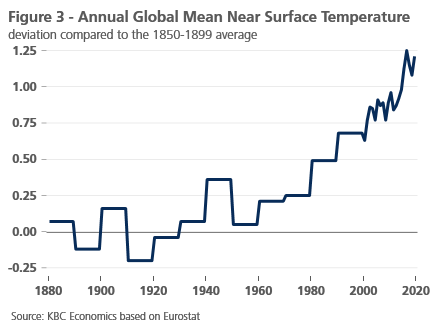

Meanwhile, global average temperatures are accelerating. Over the last few decades, global temperatures have risen sharply, and are approximately 1°C higher compared to the 1850-1899 (pre-industrialisation) baseline (figure 3).

Multiple international institutions, including the Word Bank and the United Nations, have published repeated warnings about the importance of maintaining global temperature increases to no more than 1.5°C compared to pre-industrial levels. According to their analyses, an increase of just 2°C would result in widespread food shortages, unprecedented heat-waves, more severe floods and more intense storms.[2],[3] Without further action, climate change could reverse decades of development progress and puts lives, livelihoods, and economic growth at risk. This is why the Paris Agreement of 2015 aims to limit global warming to well below 2°C while pursuing the means to limit the increase to 1.5°C.[4] To reach this goal, the agreement specifies that global emissions need to peak as soon as possible to achieve climate neutrality by mid-century. More specifically, the UN estimates that global emissions must be reduced by 7.6% each year until 2030 in order to limit warming to 1.5°C.[5]

Reducing emissions through carbon pricing

In recognizing the crucial role GHG emissions play in the climate crisis, and to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, the EU has pledged to reduce GHG emissions by 55% by 2030 relative to 1990 levels and to be fully carbon neutral by 2050.[6] Achieving emission reductions on this scale requires a multi-pronged approach. Innovation is key, particularly when it comes to finding more efficient and less polluting technologies and energy systems, including carbon capture technology. In order to incentivise such innovation, governments typically have three main policy tools available to encourage behavioral change, i.e. social (e.g. information campaigns), economic (e.g. subsidies or taxes) or legal (e.g. command-and-control legislation) instruments.

However, the key to an effective emissions reduction policy is understanding the market failure behind carbon emissions that needs to be addressed. That is, the high societal costs of carbon, or other GHG emissions are not monetarily priced within an unregulated market. These societal costs already burden today's society but also pose a significant threat for the sustainable development of future generations. These costs include not only the contribution of emissions to global temperature rises, but all the other negative externalities generated by the climate crisis – i.e., the costs associated with extreme weather events – including heat waves, fires, droughts, and flooding to name a few – rising sea levels, and an erosion of biodiversity. The impact can also be seen in health outcomes, damage to property, and higher costs for certain economic sectors.[7]

Hence, as an economic policy instrument, carbon pricing and taxing serve to address that market failure by raising the price of carbon emissions, which sends an economic signal to emitters. It thus provides an incentive to pursue more energy efficient production, needed innovation, and technological change (including a shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy), but it can also serve as a backstop mechanism to achieve reductions targets, even when technological progress is slow.

The two main types of carbon pricing governments use today include emissions trading systems (ETS) and carbon taxes.[8] An ETS sets a cap on emissions and requires emitters to hold a permit for each tonne of CO2 that they emit. The level of the cap determines the number of permits available and hence allowable overall emissions. An ETS thus creates a market price for emissions by creating a situation in which supply is limited and cannot freely meet demand. The cap helps ensure that a certain degree of emission reductions will take place, while also incentivizing research and investment into less polluting technologies to reduce costs for emitters.

Whereas an ETS allows the market to determine the price of emissions under a limited allocation, a carbon tax directly sets the price via a tax rate on emissions (usually as a function of the carbon content of fossil fuels used). Hence, the emissions reduction outcome of a carbon tax is not pre-defined, but such a policy will, in theory, incentivise a reduction in emissions up until a producer’s marginal abatement cost (i.e. the cost of reducing an additional unit of emissions) is equal to the carbon tax rate.

Both systems have their own strengths and weaknesses, and if set right, can reduce emissions and incentivise technological switching. As such, the correct policy instrument for a given country or region will likely depend on various economic and political factors.[9] It is likely that a combination of both approaches to carbon pricing will partly inform global climate policy going forward. However, carbon pricing alone will not be sufficient for an effective global climate policy, which will most likely require the deployment of additional supportive social and legal policy instruments.

In addition to reducing emissions, carbon pricing also generates local environmental benefits and positive externalities, such as reduced air pollution and traffic congestion. On top of that, carbon pricing can generate fiscal revenue, which can in turn be used to support the green transition. Indeed, studies suggest that the redistribution of tax revenues are a crucial factor in determining the overall welfare impact of green policies such as carbon taxes.[10] With time constraints playing a major role in avoiding irreversible damage to the planet (the UN warns that we have less than a decade), carbon pricing is increasingly seen as a key pillar for reducing emissions. Accordingly, the price of carbon is expected to increase substantially over the coming decades.

Carbon pricing in practice

At the time of writing, 46 countries and 35 subnational jurisdictions are covered by or are planning on implementing[11] carbon pricing initiatives according to the World Bank carbon pricing dashboard.[12] In 2020, these covered an estimated 12 gigatonnes of CO2, representing 22.3% of global GHG emissions. Other initiatives are still under consideration and could be implemented in the next years. Many of the systems could eventually be linked with one another under the auspices of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.[13] Article 6 enables countries to cooperate in implementing their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) towards emission reduction. This includes the possibility to implement climate change mitigation activities in one country and to transfer the resulting emission reductions to another country. Article 6 was not finalized during the last iteration of international climate talks and will again be on the agenda in November 2021 during the COP-26. This does not mean, however, that carbon pricing cooperation is impossible at the moment. One successful example is the Linking Agreement between the EU and Switzerland, that was signed in 2017. This was the first international treaty that links emissions trading systems in the world.

The EU is considered a global leader on carbon pricing initiatives, having introduced the European ETS in 2005. The EU ETS covers roughly 40% of EU emissions, including power and heat generation and other energy-intensive industries.[14] Not only has the EU ETS set a standard for an international carbon market and inspired cap-and-trade systems elsewhere, it has also seen a successful reduction in emissions from most covered sectors since 2005 (with the exception of the aviation sector).[15] Using a statistical model and sectoral emissions data, Bayer and Aklin (2020) found that the EU ETS saved more than 1 gigatonne of CO2 between 2008 and 2016. This translates to reductions of 3.8% of total EU-wide emissions compared to a world without the EU ETS.[16]

Success begets success, and the reduction goals of the EU ETS have become progressively more ambitious over time. The EU’s 2030 climate and energy framework, for example, which was adopted in 2018, sets a target reduction in GHG emissions of 40% relative to 1990 levels. Under the Green Deal framework, which was proposed in September 2020, that emissions reduction target for 2030 has been increased to 55% relative to 1990 levels. The more precise path to reaching these new emissions targets should be detailed in new legislative proposals expected by mid-July 2021.[17]

However, it is already foreseen that proposed changes to the EU ETS will entail a faster reduction in the total amount of permitted emissions each year, and an expansion of the EU ETS to high emitting sectors not yet covered, particularly maritime transport, transport in general and potentially buildings (including heating).[18],[19] This reform of the ETS is also being complemented by a revision of the European Energy Taxation Directive to bring it more in line with the EU’s emissions reduction targets (i.e. levelling the playing field between electricity and other energy sources), and an exploration of the implementation of a carbon border tax (and potentially domestic carbon taxes).[20]

A carbon border tax or border carbon adjustment would serve to prevent adverse effects on European competitiveness from jurisdictions where climate policy is far less restrictive. Indeed, a higher carbon price in Europe could theoretically lead to carbon leakage, where production is moved abroad to minimize costs. This would undermine both European competitiveness and the sustainability goals of higher carbon prices in the first place, as emissions in other jurisdictions would increase as a result.

The current EU ETS does account for carbon leakage, particularly in the most energy-intensive industries and those sectors with higher non-EU trade intensity. However, rather than enforce a carbon border tax, the current framework allows for certain at-risk sectors to receive a higher share of free emissions allocations.[21] While this appears to have prevented carbon leakage in the past, the expected expansion of the scope of the ETS and the more rigorous reduction targets are not necessarily compatible with this approach.

There are, however, numerous criticisms of implementing a carbon border tax, including the disruptions it could inflict on the multilateral trade system (as some countries may deem such a tax green protectionism[22], incompatible with WTO rules, and unfair for emerging economies), and the fact that it would be practically difficult to enforce (given that third country trading partners would need to accurately report the carbon content of their products).[23] It may be possible to overcome these criticisms and difficulties, however, and a well-designed carbon border tax could even incentivise further multilateral policymaking on climate-related issues.[24]

Higher prices in the (near) future

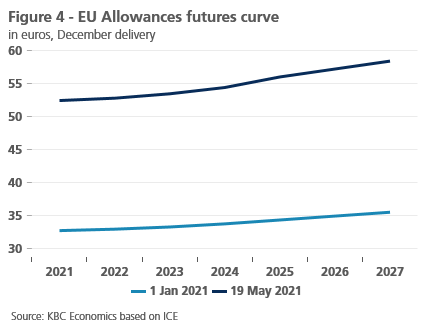

No matter the framework specifics, the cost of carbon emissions is likely to increase in the near future and continue increasing over the next several decades. Futures prices for EU ETS allowances (EUA) across the curve have already risen sharply since the announcement of the EU Green Deal framework in September 2020 (figure 4). Futures prices for end-2026, which averaged only EUR 30.00 in September 2020 increased to an average of EUR 57.00 in May 2021. The sharpest increase occurred in 2021, as both the post-Covid-19 economic normalisation in Europe and the legislative proposals to cement the Green Deal into law are on the horizon. While the sharp rise in European carbon prices has sparked concern for some, particularly producers that fall (or will be falling) within the ETS, it is also a welcome development for those that stress the importance of higher carbon prices for reaching climate goals.

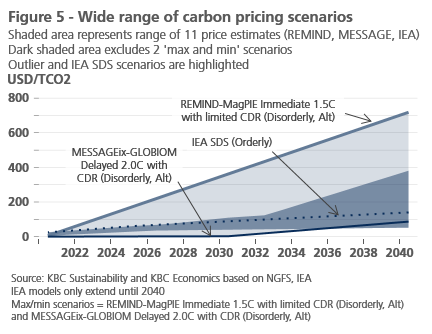

Indeed, most international organizations that have laid out climate scenarios (such as the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) or the International Energy Association (IEA)) acknowledge the need for higher carbon prices going forward. The trajectories put forth in various scenarios, however, depend on a number of assumptions, particularly regarding the policy responses and timing of those policy responses by governments, and the successful or unsuccessful development of carbon capture technology.[25]

A quick look at three highly recognized climate scenario models (MESSAGE-GLOBIOM, REMIND-magPIE (as of June 2020)[26], and the IEA World Energy Model (as of October 2020)[27]) and their variations (based on the above-mentioned assumptions) gives a rough overview of various possible paths for global carbon prices (figure 5). However, it should be noted that the carbon prices in these scenarios are a monetary expression of the full 'climate policy toolbox' governments might use to reach their climate goals (i.e. the mix of social, economic and legal instruments and their effects).

While most trajectories fall within a relatively limited range until 2030, it is worth noting that EUA futures prices (in USD) for end-2022 (as of end-May 2021) are already above the price levels indicated in most, but not all scenarios for 2022. That EU ETS prices are already above the levels prescribed in most scenarios is perhaps not surprising. Afterall, these are global models and the EU is a front runner in carbon pricing with an eye toward a more expanded use of carbon pricing to meet climate objectives in the near future. It is also worth noting that the EU ETS price currently applies only to certain, high-emissions sectors and therefore is not representative of an economy-wide carbon price. Rising ETS prices feed into fears that the EU ETS will increasingly create competitive disadvantages for EU companies, especially as the scope of the EU ETS will likely be extended. The EU’s intention to introduce a carbon border tax in 2022 could, if well designed, alleviate some of these fears.

Internal carbon pricing

The transition to a low-carbon economy will result in both opportunities and challenges for businesses, whether they are part of the traditionally high-polluting sectors or not. One tool that businesses are increasingly adopting to prepare themselves for higher carbon prices and a heightened focus on sustainability by stakeholders and regulators is internal carbon pricing (ICP). An ICP attaches a price to greenhouse gas emissions, allowing businesses to address the risks (and opportunities) that may arise as countries pursue their climate goals and to consider those risks in monetary terms.[28] This price can, and should, change over time, which in practice means ICP will incorporate a forward-looking price schedule rather than a single price point.

It can be implemented in various ways, including an internal carbon fee, where emissions within the company or a department are charged, creating a revenue stream that can be used for meeting sustainability goals, or a carbon shadow price, where a hypothetical cost is used in risk and operational assessments to better understand exposure to higher carbon prices.[29] The sustainability impact of the latter will depend on how the shadow price is implemented and enforced within a company.

According to the CDP’s 2021 report on companies’ disclosures of the use of ICPs, over 2,000 companies (from a sample of over 5,900) are currently using or planning to use ICP – an 80% increase over the past five years.[30] According to the survey, the objectives of internal carbon pricing vary from meeting internal climate goals (like driving low-carbon investments), to navigating new regulations, complying with stakeholder expectations and stress testing investments or business models.

Unsurprisingly, the use of ICPs varies across industries and is highest in sectors where carbon pricing schemes are already in place, like the power and fossil fuel sector. However, there is also growing interest in ICPs in the financial services sectors. According to the CDP, there was a 6.2% increase in the number of financial service companies instituting (or planning to institute) an internal carbon price between 2019 and 2020. This amounts to 52.4% of financial services companies surveyed, and is in line with the recommendations made by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) that financial institutions use internal carbon pricing as “a fundamental metric to assess climate-related risks and opportunities.”[31] The TCFD goes even further in its recommendations, noting that while most financial institutions currently use ICP to improve operational sustainability, the tool should eventually be extended to the portfolio level to assess traditional market and credit risks.

Conclusion

The climate crisis and its mitigation will be major driving forces behind both policy developments and economic developments in the coming years. With emissions reductions a key factor in keeping global temperature rises within the goals of the Paris Agreement, carbon pricing is set to become a more prominent policy tool used by governments to achieve their climate agendas. No matter the way in which carbon pricing is implemented (whether through an expansion of emission trading system, carbon taxes, or border carbon adjustments), the takeaway message is that the cost of emitting will continue to rise in the coming years. As carbon pricing develops, so will the use of Internal Carbon Pricing by companies. By attaching a pecuniary cost to direct and indirect emissions, companies can not only support the ecological transition, but also prepare themselves for the opportunities and risks that will come with it.

Endnotes

1. . Global Energy Review: CO2 Emissions in 2020 – Analysis - IEA

2. . Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must Be Avoided (worldbank.org)

3. . Summary for Policymakers — Global Warming of 1.5 ºC (ipcc.ch)

4. . The Paris Agreement | UNFCCC

6. . State of the Union: Commission raises climate ambition (europa.eu)

7. . Climate change consequences | Climate Action (europa.eu)

8. . Pricing Carbon (worldbank.org)

9. . Stavins, Robert (2019) “Carbon Taxes vs Cap and Trade: Theory and Practice.”

11. . Formally adopted through legislation and with an officially planned start date

12. . Carbon Pricing Dashboard | Up-to-date overview of carbon pricing initiatives (worldbank.org)

13. . ADOPTION OF THE PARIS AGREEMENT - Paris Agreement text English (unfccc.int)

14. . EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) | Climate Action (europa.eu)

15. . Emissions trading: greenhouse gas emissions reduced by 8.7% in 2019 | Climate Action (europa.eu)

16. . The European Union Emissions Trading System reduced CO2 emissions despite low prices | PNAS

17. . 2030 climate & energy framework | Climate Action (europa.eu)

18. . Climate change – updating the EU emissions trading system (ETS) (europa.eu)

21. . Carbon leakage | Climate Action (europa.eu)

22. . WTO | Environment - environmental requirements

23. . Demystifying carbon border adjustment for Europe’s green deal | Bruegel

24. . Border Carbon Tariffs: Giving Up on Trade to Save the Climate? | Bruegel

25. . 820184_ngfs_scenarios_final_version_v6.pdf

26. . NGFS Scenario Explorer (iiasa.ac.at)

27. . Documentation – World Energy Model – Analysis - IEA

28. . Ecofys, The Generation Foundation and CDP (2017), How-to guide to corporate internal carbon pricing – Four dimensions to best practice approaches

29. . Ecofys, The Generation Foundation and CDP (2017)

30. . Putting a price on carbon - CDP

31. . https://www.carbonpricingleadership.org/s/33368-TCFD-and-Carbon-Pricing-Executive-Brief-final.pdf

References

“2030 Climate & Energy Framework.” Climate Action - European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/strategies/2030_en. Accessed 17 June 2021.

Bayer, Patrick, and Michaël Aklin. “The European Union Emissions Trading System Reduced CO2 Emissions despite Low Prices.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 117, no. 16, 2020, pp. 8804–12. Crossref, doi:10.1073/pnas.1918128117.

Burggraeve, K., et al. “Fighting Global Warming with Carbon Pricing: How It Works, Field Experiments and Elements for the Belgian Economy.” NBB Economic Review, 2020, www.nbb.be/en/articles/fighting-global-warming-carbon-pricing-how-it-works-field-experiments-and-elements-belgia-0.

“Carbon Leakage.” Climate Action - European Commission, 16 Feb. 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets/allowances/leakage_en.

“Carbon Pricing Dashboard | Up-to-Date Overview of Carbon Pricing Initiatives.” The World Bank, https://carbonpricingdashboard.worldbank.org. Accessed 17 June 2021.

“Climate Change Consequences.” Climate Action - European Commission, 16 Feb. 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/change/consequences_en.

“Climate Change – Updating the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS).” European Commission - Climate Action, https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12660-Climate-change-updating-the-EU-emissions-trading-system-ETS-_en. Accessed 17 June 2021.

“Commission Launches Public Consultations on Energy Taxation and a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.” Taxation and Customs Union - European Commission, 23 July 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/news/commission-launches-public-consultations-energy-taxation-and-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en.

“Cut Global Emissions by 7.6 Percent Every Year for Next Decade to Meet 1.5°C Paris Target - UN Report” UNFCC, https://unfccc.int/news/cut-global-emissions-by-76-percent-every-year-for-next-decade-to-meet-15degc-paris-target-un-report.

Ecofys, The Generation Foundation and CDP, How-to guide to corporate internal carbon pricing – Four dimensions to best practice approaches, December 2017. Prepared under the Carbon Pricing Unlocked partnership between the Generation Foundation and Ecofys in collaboration with CDP.

“Emissions Trading: Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduced by 8.7% in 2019.” Climate Action - European Commission, 4 May 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/news/emissions-trading-greenhouse-gas-emissions-reduced-87-2019_en.

“Environmental Requirements and Market Access: Preventing ‘Green Protectionism.’” WTO | Environment, www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/envir_req_e.htm. Accessed 17 June 2021.

“EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS).” Climate Action - European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/clima/policies/ets#tab-0-0. Accessed 17 June 2021.

“Executive Briefing: Carbon Pricing and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).” Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, May 2018

Horn, Henrik, and André Sapir. “Border Carbon Tariffs: Giving Up on Trade to Save the Climate?” Bruegel, 29 Aug. 2019, www.bruegel.org/2019/08/border-carbon-tariffs-giving-up-on-trade-to-save-the-climate.

IEA (2021), Global Energy Review: CO2 Emissions in 2020, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/articles/global-energy-review-co2-emissions-in-2020.

IEA (2020), World Energy Model, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-model

IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp.

“NGFS Climate Scenarios for Central Banks and Supervisors.” Network for Greening the Financial System, June 2020, www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/medias/documents/820184_ngfs_scenarios_final_version_v6.pdf.

“NGFS Scenario Explorer.” NGFS Scenario Explorer Hosted by IIASA, https://data.ene.iiasa.ac.at/ngfs. Accessed 18 June 2021.

“The Paris Agreement.” UNFCC, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

“Pricing Carbon.” World Bank, www.worldbank.org/en/programs/pricing-carbon. Accessed 17 June 2021.

“Putting a Price on Carbon - CDP.” CDP - Disclosure Insight Action, June 2021, www.cdp.net/en/research/global-reports/putting-a-price-on-carbon.

Simson, Kadri. “Speech by Commissioner Simson at the AmCham EU Transatlantic.” European Commission, 25 Mar. 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/commissioners/2019-2024/simson/announcements/speech-commissioner-simson-amcham-eu-transatlantic-conference-global-leadership-transatlantic_en.

“State of the Union: Commission Raises Climate Ambition and Proposes 55% Cut in Emissions by 2030.” European Commission - Press Corner, 17 Sept. 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1599.

Stavins, Robert. “Carbon Taxes vs Cap and Trade: Theory and Practice.” Discussion Paper ES 2019-9. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Project on Climate Agreements, November 2019.

Wolff, Guntram. “Demystifying Carbon Border Adjustment for Europe’s Green Deal.” Bruegel, 31 Oct. 2019, www.bruegel.org/2019/10/demystifying-carbon-border-adjustment-for-europes-green-deal.

World Bank. 2012. Turn Down the Heat: Why a 4°C Warmer World Must Be Avoided. Washington, DC. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/11860 License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 IGO.