The ECB’s greenflation dilemma

Rising energy prices worldwide provide a foretaste of the inflationary pressure that the green transition may create. Like a negative supply shock, carbon taxes and energy price increases are as such inflationary and weigh on the supply side of the economy. However, unlike the oil price shocks of the 1970s, there are now tax revenues that can be recycled, for example to investment or transfers to households. On balance, provided good macroeconomic management is in place, the impact of the climate transition will show up, not so much in growth, but more so in higher inflation. As a result, the ECB faces a dilemma. If it pursues its primary objective of price stability through tighter monetary policy, it may do so at the expense of its implicit secondary objectives. This may pose a dilemma for the ECB to fight inflation, via slowing economic growth, at a time when the economy is undergoing a green transition with higher prices.

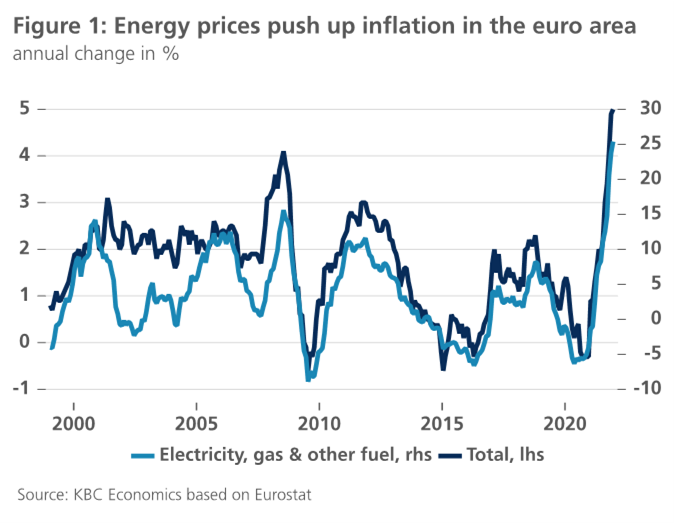

In December 2021, inflation in the euro area reached 5% year-on-year. Besides reopening effects and supply side distortions, sharply higher energy prices played an important role (Figure 1). It appears that more expensive commodities, in particular oil, gas and electricity, are a permanent phenomenon. The energy transition with EU ETS and other climate-friendly regulations reinforce this trend. This poses a dilemma for central banks such as the ECB. After all, the period of inflation systematically below the inflation target seems to be over. For the first time since the financial crisis, central banks must once again balance the pursuit of price stability against supporting economic growth, ensuring favourable financing conditions for governments and businesses, and for climate-related objectives.

Supply shock differs from the 1970s

The costs of the green transition as such constitute a negative supply shock. Higher energy costs through EU ETS and a range of regulations, at least in a transition phase, increase production costs and reduce the productive capacity of the economy. However, the current supply shock differs in one important respect from the shock of the 1970s ((Schnabel (ECB), (2022)). The higher energy prices in the 1970s led to a collective wealth loss for oil-importing countries through a deterioration of their international terms of trade. Indeed, the money for the higher energy bill was transferred to the oil-exporting countries. In the current climate transition, the proceeds from carbon taxes and the ‘carbon border adjustment mechanism’ remain available for domestic ‘recycling’ in the form of (green) investments, transfers or tax cuts. This leads to a positive demand shock that occurs simultaneously with the negative supply shock.

The Spanish central bank (Working Paper 2119 (2021)) simulated what the joint impact of both shocks could be on economic growth and inflation in Spain. The simulated scenario is that of an immediately fully implemented carbon tax (including a “carbon border adjustment mechanism”), the proceeds of which are recycled in various ways. Figure 2 shows the results if this recycling is done through transfers to households.

As we would theoretically expect, the simulation suggests that the net impact of a negative supply shock and a positive demand shock on private consumption and real GDP is likely to be small. However, the impact on inflation is particularly striking. Indeed, both shocks are inflationary in their own right, and reinforce each other.

Implications for monetary policy

The green transition therefore represents a major challenge for monetary policy (see also KBC Economic Opinions of 24 October 2019 and of 7 January 2021). To offset the inflationary effect of the green transition, the central bank will have to start pursuing not only a neutral, but even a restrictive policy quite soon. This applies to both the policy rate and the purchase programs. In doing so, the ECB must weigh mutually conflicting policy objectives. Its primary objective remains unequivocally the pursuit of price stability in the euro area, translated into a symmetric and forward-looking inflation target of 2% over the medium term. In addition, however, the ECB also considers, for example, climate-related factors as its (secondary) policy objectives. In its updated policy strategy, it explicitly refers to the role that, among others, the Corporate Sector Purchase Program (CSPP) can play in this regard in the medium term. As of January 21, 2022, EUR 315 billion worth of corporate bonds were on the ECB’s balance sheet, which it purchased under the CSPP.

The central question, however, is whether the ECB is willing and able to tighten its policy sufficiently if the goal of price stability would require it to do so. After all, the ECB would not only have to raise its policy rate, which could put pressure on the sustainability of euro area sovereign debt over the medium term. To remain consistent with its policies on the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Progam (PEPP) and the Asset Purchase Program (APP), the ECB would also have to stop its net purchases under the CSPP at some point and possibly even sell again part of those assets. That decision may become more difficult to the extent that the green transition would become more dependent on CSPP financing.

Tinbergen’s rule

We can summarize the dilemma for the ECB with Tinbergen’s rule. That rule states that policymakers need at least as many (independent) policy instruments as they have (independent) objectives. Therefore, in addition to monetary policy, fiscal policy and regulatory authorities must also play their role to achieve the various objectives of high growth, price stability and green transition together. The ECB cannot systematically add another objective with the same priority alongside price stability. This would sooner rather than later jeopardize the credibility of price stability.