The developing EU bond market

Debt issuances by the European Commission (EC) to finance NextGenerationEU (NGEU) have boosted the European Union (EU) bond market in recent years. Issues increased dramatically, and at the same time, the EC took steps to streamline the functioning of both the primary and secondary markets on the model of the market for national government debt securities. Judging by the interest premium to be paid on EU debt, this has not quite worked out yet. According to a survey of investors in EU debt, a further increase in market liquidity and a long-term perspective on issuance are key factors for the further development of this market. By 2026 - when debt issuance for NGEU expires - the outstanding volume of EU bonds is likely to double again, which should allow for a further improvement in liquidity. However, new issuance thereafter will depend on decisions to set up analogous projects. There is no shortage of needs. But politically, opinions are divided. The level of success with NGEU implementation could become an important catalyst in that respect. Though in the meantime, the EU is also borrowing for other programmes, such as for support to Ukraine.

NGEU game changer for volume growth

The European Union (EU) bond market is booming. In the past four years, the European Commission (EC) issued more than 400 billion euros of bonds, compared to just 78 billion euros in the previous 10 years. NextGenerationEU (NGEU) - the EU's massive programme to overcome the post-pandemic economic downturn by making Europe's economies greener, more digital and more resilient - was the game changer. In July 2020, NGEU allowed the EC to issue a total of 806.9 billion euros of debt on the capital market between 2020 and 2026. NGEU thereby pushed aside the principle that the EU budget should not run deficits.

Admittedly, the EC was already authorised by the European treaties to borrow money on behalf of the EU. But because of the principle of budget balance, it did so only to a limited extent and for specific purposes, such as for balance of payments support to EU countries or macroeconomic assistance loans to EU partner countries (Macro-Financial Assistance - MFA). Taking advantage of its favourable credit rating, the EU borrows money in the capital market, which it then lends to countries that would get less favourable terms by going to the capital market themselves (back-to-back loans).

For larger-scale emergency support during crises, constructions outside the EU budget were always set up, such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) or the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) during the European debt crisis in 2011-2012. Even when the pandemic broke out, the first support package to mitigate the threat of unemployment (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency - SURE) was still set up through a specific instrument.

NGEU, on the other hand, allowed for a substantial but temporary expansion of the EU budget through debt financing. 83.1 billion euros of the money raised in financial markets would be spent directly through the EU budget within the multiannual financial framework 2021-2027. The bulk of the funds would be passed on to member states, according to certain criteria, through the newly created Recovery and Resilience Facility (RFF), provided they committed to reforms and investments in a National Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP) to make their economies greener, more digital and more resilient. EUR 338 billion was available in the form of grants and EUR 385.8 billion in the form of loans. In 2023, under the REPowerEU initiative in response to the energy crisis, member states could update their RRP with measures that reduce their energy dependence.

Of the 723.8 billion euros available, a total of about 630 billion euros was allocated to member states based on RRPs. By the end of 2023, the EC had effectively disbursed €220.5 billion of that. Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the EU additionally granted Ukraine €7.2bn in MFA loans in 2021 and a further €16.5bn in loans against special benefits (MFA+ loans) in 2023.

Towards a central funding pool...

The EC has to borrow that money in the capital market. It used to go to the market according to the concrete amounts it needed for back-to-back loans. However, financing NGEU expenditure requires a more permanent revenue stream. With the launch of NGEU, the EC therefore developed a diversified financing strategy as early as 2021. This was to provide it with more flexibility and a stronger market presence. It expanded that strategy in 2023 into a unified funding approach around a central funding pool.

In comparison with treasuries of national governments, the EC now brings uniform EU bonds with maturities ranging between 3 and 30 years to the market through monthly auctions and syndicated transactions. It will also hold fortnightly auctions of short-term EU debt securities with maturities of 3 and 6 months. It announces a calendar for these every six months.

The EU intends to raise 30% of NGEU funds through Green Bonds. It has developed a framework for this, which complies with the relevant principles of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). The EU's ambition is to be the largest issuer of green bonds globally. EU green bonds are included in the MSCI Global Green Bond Index.

The money thus raised in the market is pooled by the EC into a unified funding pool. From there, the money will be made available to the EU's various policy programmes.

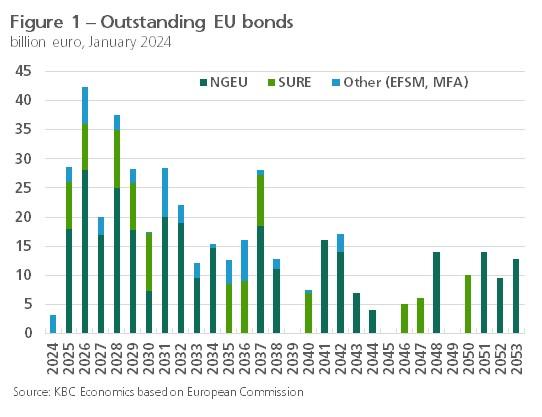

In 2023, the EC thus raised nearly €116 billion at the EU's expense. It was the fifth largest issuer in the European capital market. Outstanding debt was also placed in the central pool. At the beginning of 2024, total outstanding EU bond debt stood at €443 billion, of which €48.9 billion were green bonds (Figure 1). In addition, €15.2 billion of short-term debt was outstanding.

... and more liquidity in the secondary market

EU bonds have the highest rating (AAA) at credit agencies Fitch and Moody's, and the second highest at Standard & Poor's. They also enjoy favourable regulatory treatment. For instance, they are considered Level 1 High Quality Liquid Assets for calculating banks' liquidity ratio (Liquid Coverage Ratio) under Basel regulation and are eligible as collateral for credit operations with the ECB. In mid-2023, they were promoted from Haircut category II (for debt securities of supranational institutions and regional and local governments) to Haircut category I (for central government debt securities) in the ECB's risk framework.

The average volume of EU bonds traded in the secondary market on a quarterly basis relative to the outstanding volume is similar to that of eurozone sovereign bonds. On this basis, the EC states that the liquidity of EU bonds in the secondary market is comparable to that of classic European government bonds.

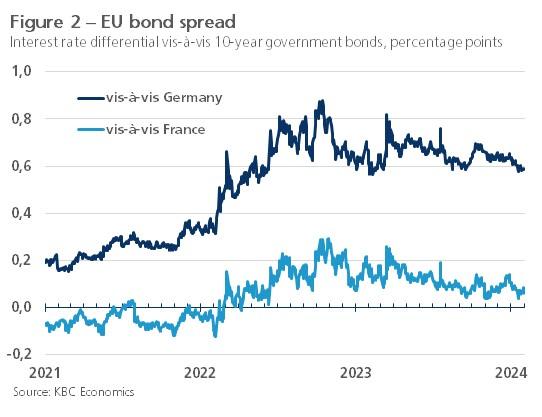

However, by other measures, such as turnover in absolute amounts or the difference between supply and demand prices (bid-ask spreads), liquidity is lower than that of German and French government bonds. Among other elements linked to pricing and the EU's lack of taxing power, this contributes to the fact that EU bonds currently have higher interest rates than, say, French government bonds, which nonetheless have a lower credit rating (Figure 2). The rise in the interest premium on EU debt following Russia's invasion of Ukraine shows that EU bonds are far from achieving safe asset status, which a fully developed market in EU bonds should lead to and which would strengthen the role of the euro as an international reserve currency1.

To promote liquidity, the EC entered into a quoting arrangement with the network of (currently 37) primary dealers in November 2023 to ensure liquidity via maximum bid-ask spreads and minimum quantities on recognised platforms. A repo facility will become operational in 2024

A survey of EU bond investors conducted by the EC in mid-2023 puts forward the inclusion of EU bonds in benchmark government bond indices (instead of in indices of supranational institutions) and the introduction of a futures contract as two important steps yet to be taken towards further market deepening. These steps would increase the similarity between the EU and national government bond markets. The introduction of a futures contract is currently under investigation. For this, 500 billion euro of outstanding debt is usually set as a minimum threshold, and this will be exceeded in 2024.

Repayment guaranteed by reserves...

European treaty law requires the EU to honour its debt service. Before NGEU, this did not pose a problem. After all, the EU usually only went to the capital market to raise money that it then lent-on to countries. The EU fulfilled its own debt service with interest and repayments by the countries it had lent the money to. So far, it has never happened that the EU has not been repaid the on-lent money, and the EU has always been able to meet its own debt service without any problems. But theoretically, things could have been worse.

Therefore, to safeguard the EU's high creditworthiness, there are structural reserves built into its financing, including the so-called headroom. This is the difference between the maximum allowed expenditure and the maximum revenue of the EU. In addition, for loans to third countries, provisions are built into the budget and sometimes, like for SURE loans or the loans to Ukraine, member states provide additional guarantees.

Maximum expenditure is set in the long-term budget (MFF or Multiannual Financial Framework). This outlines the framework for the annual EU budget for seven-year periods (currently: 2021-2027). It sets maximum expenditure ceilings for each year.

Since the EU cannot levy its own taxes, it gets its revenue from the member states on the basis of Own Resource Decisions. Traditional own resources are customs and agricultural duties, which have been supplemented by a share of member states' VAT revenue since 1979. Currently, own resources based on member states' gross national income (GNI) make up the bulk of the EU's own resources. The own resources decision sets a ceiling on member states' GNI contributions. The revenue and expenditure ceilings are set in such a way that there is always a reserve (the headroom). To ensure sufficient headroom, the ceiling on member states' GNI contributions was raised to 1.4% of GNI, and an additional limit of 0.6% of GNI is temporarily provided for NGEU debt (see below).

Indeed, with NGEU, the EU is for the first time raising substantial amounts in the capital market, which it grants to member states as subsidies. So the member states do not have to pay that money back to the EU. The intention is for the EU to acquire new own resources to repay them.

The EU must repay NGEU debts between 2028 and 2058. Through the central funding pool, the EC has created some flexibility in this regard. Bonds under NGEU are also covered until the end of 2058 by a temporary increased ceiling on GNI contributions amounting to 0.6% of EU GNI, as additional headroom. However, this is intended as an additional safeguard to enable debt servicing under exceptional circumstances. The repayment of EU bonds, the proceeds of which have been distributed to member states as subsidies, should in principle be made from new EU own resources.

... but requires new EU own resources

The own resources decision of 1 June 2020 introduced a first new category of own resources based on non-recycled plastic waste. Two more packages of new own resources were planned to follow.

In December 2021, the EC proposed an initial package of three new categories of own resources based on 1) auctioned emission allowance (ETS) revenue, 2) the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, and 3) revenue under the OECD/G20 agreement on international corporate taxation. Although the first package was supposed to come into force on 1 January 2023 according to the initial agenda, discussions are still ongoing. In June 2023, the EC published its proposals for a second own resources package, which should take effect from 2026.

Further growth in the pipeline...for how long?

The lack of taxing power makes the EU dependent on revenues granted to it by member states and basically reduces its creditworthiness compared to sovereign nation states. The difficult process of acquiring new own resources could therefore be an obstacle to the further development of the EU bond market. However, according to the EC's survey mentioned above, only 23% of EU bond investors consider the absence of direct tax competence for the EU to be a major obstacle to their willingness to continue investing in EU bonds. They consider secondary market liquidity and the long-term prospect of new issuance much more important.

As mentioned above, initiatives were taken in the recent past to promote liquidity and further initiatives are on the agenda. New issuance is also assured in the short and medium term. To finance further NGEU loans and grants, the EC is estimated to need to raise around EUR 150 billion annually through 2026. That alone suggests a doubling of the market size ahead. Support to Ukraine and the Western Balkans could further increase the financing requirement.

However, further growth in the longer term, after NGEU ends in 2026, is much less certain. NGEU was decided during the pandemic as an exceptional, one-off and time-limited crisis measure. So it is by no means a foregone conclusion that it will be followed up, although there are numerous investment needs that, from an economic point of view, could well be financed by joint European debt issuance.

Admittedly, according to the subsidiarity principle, government tasks and spending are preferably decentralised as much as possible. That way, they can best meet local needs and preferences. Such tasks are best left to the member states or even lower levels of government, which must also assume financial responsibility for them. Such public tasks do not qualify for more European intervention.

But for addressing cross-border problems of common European interest, government action at the European level can in principle bring efficiency gains. Many acute contemporary problems, such as asylum and migration, defence, the strengthening of cross-border networks for energy and transport or measures in the fight against global warming (which will not be resolved by 2026) meet these criteria and are eligible for (co-)financing from the EU budget. Many of these challenges require investments, which are eligible for debt financing.

An ECB report concludes that a debt-financed EU climate and energy security fund of €500 billion by 2030 would be an effective and efficient option to address public climate and energy-related investment needs. It would help the EU and its member states - especially those with tough fiscal consolidation ahead - to meet their commitments under the Paris climate agreement.

According to that report, by analogy with NGEU, the creation of such a fund would also be feasible within the current legal and institutional framework. However, political opinions on such new initiatives are divided. For instance, the idea of a European Sovereignty Fund, which EC President von der Leyen launched in September 2022 as a European response to the US Inflation Reduction Act, has remained (largely) dead in the water until today.

Indeed, apart from principle-political objections, such initiatives are only decided upon with difficulty because of the danger of moral hazard and permanent income transfers from richer to poorer countries, which can be an undesirable consequence. It is these same obstacles that hinder a decision on a central fiscal instrument to cushion economic shocks in the euro area, even though such an instrument is necessary for the sake of a currency union's stability. Debt creation at the European level must also be accompanied by greater fiscal discipline in member states. All this requires a political strengthening of the EU, which must be accompanied by further democratic legitimisation.

Finally, whether or not there will be a sequel to NGEU may also depend on how successful its implementation is. As already mentioned, NGEU aims to make European economies greener, more digital and more resilient with reforms and investments. To promote the realisation of the objectives, the EC effectively makes the pledged funds available to member states only after the realisation of targets or achievement of milestones by member states.

This performance-based approach should increase the chances of success and is to be welcomed in principle. However, in practice it comes up against criticism that targets are often too vague or not sufficiently result-oriented. Industry, meanwhile, complains that accessing NGEU funds is fraught with red tape - a criticism, incidentally, that is often levelled in relation to EU funds.

Successful implementation - though still far from being achieved - would nevertheless promote economic growth and could strengthen convergence between countries and regions. This could contribute to a more fertile ground for broader political and social support for European cooperation. And it could pave the way for new European initiatives, which could be financed by European debt issuance, along the lines of NGEU and would promote the long-term growth of the EU bond market.

1 For a discussion of the development of the interest rate differential between EU bonds and bonds of European countries, see: "The rising cost of European Union borrowing and what to do about it".

2 An own resources decision is taken unanimously by the Council and must be ratified by the competent domestic authorities according to the constitutional rules of each member state

3 See for example: "The EU Recovery and Resilience Facility falls short against performance-based funding standards" of "The Recovery and Resilience Facility What are we really monitoring with a performance-based approach".