The climate change debate within the ECB is warming up

Climate change is playing an increasing role in the debate on the future policy strategy of central banks. On a global scale, that debate is informed and supported by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), with 83 members, including the four major central banks worldwide (Fed, ECB, Bank of Japan and the Chinese central bank). At the European level, that debate is also part of the review of the ECB’s policy strategy, the results of which are expected in the second half of 2021. There is to some extent a consensus within the ECB on a number of aspects arising from the ECB’s role as prudential supervisor. Those aspects that focus more on monetary policy itself are more controversial, and the arguments put forward are often more principled.

On 15 December 2020, the US central bank joined the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). This is a global network of central banks, regulators and international institutions established at the Paris One Planet Summit on 12 December 20171. The objective of the NGFS is “to share best practices, contribute to climate and environmental risk management and mobilise mainstream funding sources for the transition to a sustainable economy”.

With the entry of the Fed in late 2020 (at the end of the Trump presidency), all major central banks (the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the Chinese central bank) are now members of the NGFS. Many individual central banks of the Eurosystem (ESCB), including the National Bank of Belgium, are also part of it. According to the NGFS, the increase in the number of members from 8 at the start to currently 83 (and 13 observers - including BIS, IMF, OECD and World Bank) means that all globally systemically important financial institutions are now being supervised by members of the NGFS.

Climate change and monetary policy

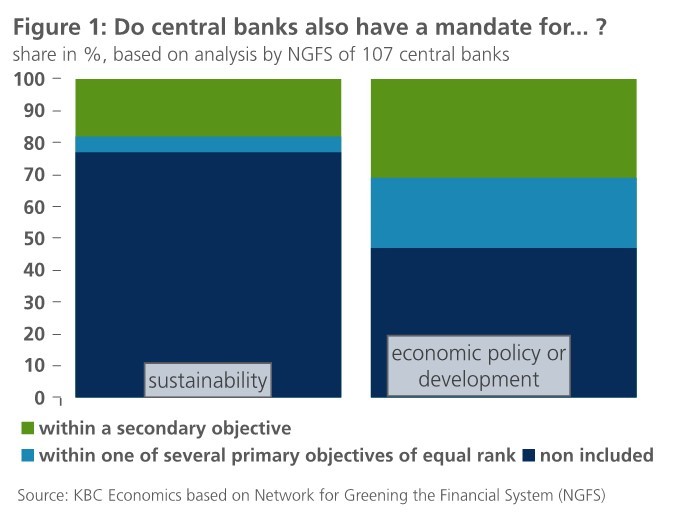

The growing role of the NGFS illustrates the rapidly increasing weight of climate change issues in the debate on the future role of monetary policy (see also Figure 1 for the possible scope for climate change issues in the policy strategy of central banks, according to their mandates). ECB President Lagarde reiterated in December that the impact of climate change will play a prominent role in the ECB’s ongoing policy review, which is likely to lead to conclusions in the second half of 2021. The impact of climate change on monetary policy is probably one of the more controversial items on the agenda, together with the review of the definition of the inflation target itself.

The rationale for the relevance of accelerating climate change to monetary policy is based, among other things, on the following elements (see Coeuré, lecture 8 November 2018). Climate-related events increase overall economic volatility and may thus make it more difficult for central banks to identify economic shocks in a timely manner. Such identification is all the more important since climate-related events are often permanent supply shocks. In contrast to demand shocks, they create a trade-off by the central bank between stabilising inflation and economic growth. Most climate-related shocks are likely to be relatively persistent. In contrast to temporary shocks, more permanent shocks give central banks less room to remain on the sidelines. Finally, climate change makes extreme shocks more likely. These ‘fat tails’ in the probability distribution of shocks are facilitated by the fact that climate-related risks may be more systemic (i.e. correlated) and less country or sector-specific. In principle, central banks are well armed to absorb such symmetric (systemic) shocks. However, in order to respond appropriately, central banks will probably have to make more pronounced policy moves in the future.

The ECB’s various asset purchase programmes fit into this framework. They serve primarily to support the economic recovery and to bring inflation back towards the policy target of just under 2%. In addition, they also facilitate the financing of the European fiscal stimulus package SURE and the Next Generation EU Recovery Fund, the cornerstone of EU climate policy. The ECB’s role in this is consistent with its Statute, which stipulates that the ECB must support the EU’s general policies as long as the condition of price stability is met.

In addition, there is a broad consensus within the ECB that, as prudential supervisor, it can ensure that financial institutions take full account of climate impact in their risk analyses (see, e.g., Schnabel, lecture 28 September 2020). According to the ECB, this can facilitate the correct pricing of financial instruments. It also seems uncontroversial that the ECB translates the actual climate risks into the ‘haircuts’ used for the collateral it uses when lending money to commercial banks.

No consensus

However, there is currently no consensus within the ECB’s Governing Council as to whether certain corporate bonds should be excluded as collateral solely as a result of the sector in which the issuer operates. The question also arises as to whether, as part of its Corporate Sector Purchase Programme, the ECB should exclude or limit purchases of assets from certain sectors compared to their market share. ECB Governor Schnabel challenges the ‘market neutrality’ principle of the ECB’s purchase programme, and is in line with ECB President Lagarde’s view on this.

Schnabel argues that there are market failures that the ECB can correct, such as the lack of information on the economic activity of a bond issuer, and the lack of a generally applicable ‘correct’ cost for carbon emissions. Schnabel also argued that certain bonds should be excluded from the ECB’s purchase policy in order to prevent the ECB from financing projects that conflict with the EU’s objective of CO2 neutrality by 2050. However, this second argument in itself has nothing to do with correcting market failures.

According to the President of the Bundesbank Weidmann, however, it is not the task of the ECB to penalise or promote certain sectors - through a targeted asset purchase programme - nor to correct market failures or lack of political decisions (FT Opinion 19 November 2020). In this way, central banks would undermine their independence. For Weidmann, the ECB’s asset purchase programmes serve only as a means of achieving price stability, and should not themselves create any additional market distortions of their own.

There are also critical voices outside the ECB. The president of the German research institute Ifo, Clemens Fuest, did not agree with the EU’s taxonomy of financial assets based on their sustainability (FAZ 22 October 2020). According to him, this is a bureaucratic classification of economic sectors, leading to a planned economy and a control of capital allocation.

In other words, the conclusions of the ECB’s policy review are far from certain. In particular, there is as yet no consensus as to how far the potential implications of climate change issues on the various aspects of ECB policy reach. It is precisely to support, inform and coordinate such discussions and to promote a coherent approach worldwide that the Network for Greening the Financial System can play an important role.

1Eight central banks and supervisors established the NGFS: the Banco de Mexico, the Bank of England, the Banque de France and the Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (ACPR), the Nederlandsche Bank, the Deutsche Bundesbank, the Finansinspektionen (the Swedish FSA), the Monetary Authority of Singapore, and the People’s Bank of China.