Socio-demographic trends are changing Belgian housing market

- More and smaller households

- Lower price pressure expected due to demographics

- Greater flexibility in housing supply

- Care real estate has yet to peak

- Higher residential mobility

Read the publication here or click here to open PDF

Socio-demographic trends have a major impact on the functioning of the housing market. In practice, this is mainly reflected in the impact of household formation behaviour on housing demand and thus on residential property pricing. That behaviour determines the numbers and composition of households and, in this way, the required housing stock and types. Conversely, household formation is also influenced by the housing market situation, in particular the availability of good-quality and affordable housing. In this research report, we discuss the reciprocal relationship between socio-demographic factors and the housing market in a Belgian context. Among other things, we focus on family dilution, ageing and residential mobility among the population and, where possible, look ahead into the future. One conclusion is that, via slower growth in the number of households, there will probably be somewhat less pressure on house prices in the coming decades than was the case in previous decades. Another conclusion is that the more complex life course and cohabitation of citizens, as well as the required geographical labour mobility, will require greater flexibility and diversity of housing supply.

Population dynamics have obvious implications for a country's housing needs. Yet the demographic impact is far from unambiguous: a change in the total population is not necessarily reflected in a corresponding change in housing demand. After all, births take place in families that already have housing (although they sometimes go in search of more spacious accommodation) and deaths do not result in housing becoming vacant if the remaining partner continues to live there. Even with net immigration, the demand for housing does not necessarily increase linearly, although here the link is stronger. For example, some immigrants may live temporarily or permanently with relatives, which means that the demand for new housing units is lower than the number of immigrants would suggest.

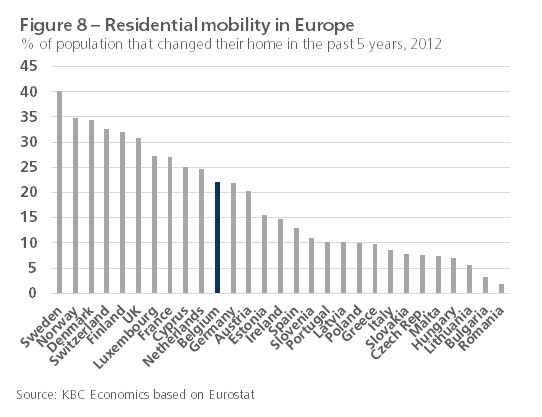

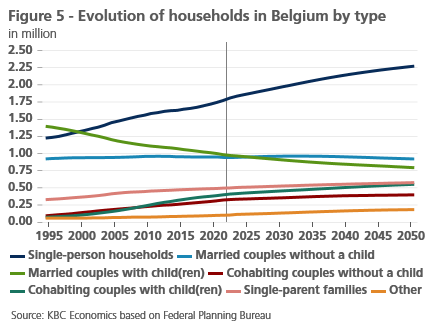

More than population trends, the evolution of the number of households determines the need for housing. In recent decades, that number increased sharply in Belgium, partly because households became systematically smaller on average (Figure 1). This fragmentation (also called 'family thinning') was related to a number of fundamental changes in the composition of households. On the one hand, the position of the classic family (married couple with children) within the whole of households weakened, partly due to a sharp increase in the number of divorces. This gave rise to a greater variety of cohabitation forms (co-parenting, LAT relationships,...). In addition, there was a strong increase in the number of one-person households (singles), among the elderly due to the ageing of the population, but also increasingly among the younger generations (often as a temporary status).

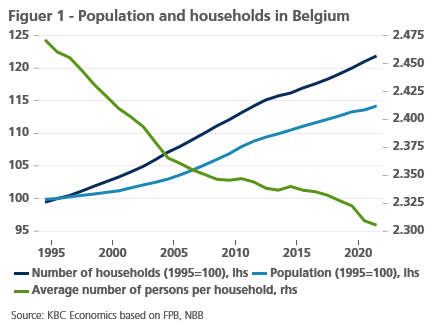

Family dilution caused the average number of members in a household to fall from 2.8 at the beginning of the 1980s to 2.3 today. During that period, the number of households in Belgium increased by 1.4 million to over 5 million units today. Especially in the first decade of this century, the increase was quite robust, averaging 0.9% per year. It then weakened somewhat, as dilution also played less of a role, but in recent years the increase has been more intense again. Not coincidentally, this dynamic translated into corresponding house price increase dynamics, with especially strong price increases before 2008 and during the most recent years (Figure 2). The KBC model, which explains Belgian house prices econometrically in the long term through a set of fundamental determinants, also points to a significant positive impact of the evolution of households on that of house prices. More precisely, it estimates the elasticity at 2.16. This means that a 1 percentage increase in the number of households leads to a more than 2 percentage increase in house prices.

Lower price pressure expected due to demographics

According to the Federal Planning Bureau's latest demographic projections (FPB, January 2023), the number of households in Belgium will continue to increase by 0.64 million between 2022 and 2050, from 5.06 to 5.70 million. At 0.4% per year on average, its growth over that period will remain even stronger than population growth (0.3% per year). Thus, the average household size continues to decline a little further. But this does mean that the average annual growth rate of households is significantly lower than average in recent decades (Figure 2). This deceleration implies that there will probably be less pressure on house prices from demographics in the coming decades than in past decades.

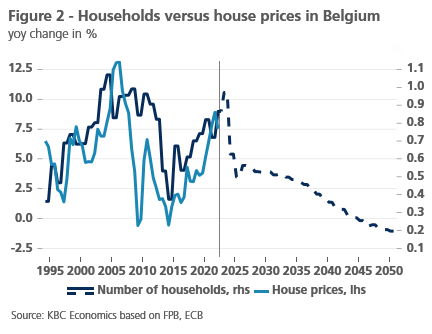

The above reasoning simply assumes that there is a one-to-one relationship between the number of households and the housing stock and that 0.64 million homes will therefore need to be added in Belgium until 2050. However, in reality (as between the total population and the housing stock), there is not a perfect relationship between the number of households and the number of housing units. This is because households are becoming increasingly pluralistic and difficult to delineate 'residentially' (e.g. singles living together in one dwelling anyway), but also because of the increasing number of second homes and student rooms and the use of housing units for tourism. This makes estimating future demand for additional housing very difficult. In addition, the household projections themselves are surrounded by a great deal of uncertainty, mainly related to the size of future migration flows and whether or not there is a strong further trend of household dilution.

Regarding the relationship between householders and housing units, it is notable that the number of available housing units has increased more than the number of households in recent years (Figure 3). This is in stark contrast to the situation at the beginning of this century, when the reverse occurred, which helps explain the sharp rise in prices during that period. The reversal that has taken place since 2014 indicates that the supply of housing in Belgium, at least in terms of volume, has recently adapted well to demographic trends, and thus to the need for additional housing. The increase in the ratio of housing units to households is indeed partly explained by the increased number of non-principal residences, including second homes and student rooms. But it may also reflect that the housing shortage that prevailed locally in Belgium has (partly) dissipated and may be turning into an oversupply of housing here and there. That too, apart from the lesser dynamics of the number of households, may temper the further rise in house prices, at least in the shorter term.

In the longer term, the supply of new housing, in addition to demand, obviously remains a major driving factor for property prices. On that front, physical constraints on spatial planning are at play in Belgium, especially in already densely populated and built-up Flanders. While the intensity of demographic pressure may weaken in the coming decades, the number of households continues to rise, which will require additional space for housing. The premise of what has come to be called the 'concrete stop' or 'building shift' in Flanders is that housing development will henceforth have to be maximised by transforming existing built-up spaces and minimised by taking up open and unbuilt space. From 2040, it would then, in principle, no longer be possible to build on open space in Flanders. The question remains to what extent new construction would then become more difficult to achieve. If yes, there could be a price driving effect. But to the extent that current fragmented housing with a lot of underutilisation (e.g. houses with bedrooms in surplus) can be eliminated, there need not necessarily be that effect.

Greater flexibility in housing supply

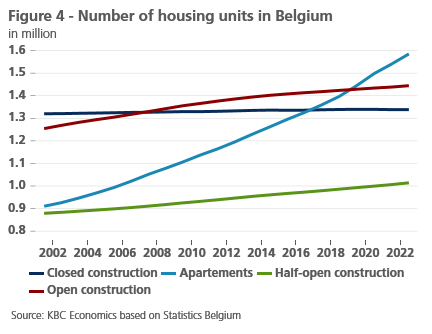

In addition to its impact on the required housing stock, family formation behaviour also affects the nature of housing, specifically the types of housing required. In particular, the more complex life course and cohabitation patterns of citizens leads to an ever-increasing variety of housing needs. Over the past two decades, the trend of family thinning (especially the strong growth in the number of single-person households, often elderly people) created a relatively high demand for smaller housing units (flats, studios or service flats). This so-called 'apartmentisation' of the housing stock is reflected in the Statbel building stock figures (Figure 4). Between 1995 and 2022, the number of flats in Belgium doubled and their share in the total housing stock rose from 19.3% to 29.5%.

According to the Federal Planning Bureau's (FPB) demographic projections, the number of one-person households in particular will continue to increase significantly in the coming decades (figure 5). At the beginning of the 1990s, their share of all households was less than 30%. By 2022, it was 35.7% and is expected to reach 39.8% by 2050. This development will further fuel the trend of living smaller. In addition, forecasts say that less stable, traditional relationships (especially married couples with children) will continue to give way to other, often more pluralistic forms of living together. The latter are sometimes accompanied by greater volatility, which will require greater flexibility in housing supply. If the supply of housing does not sufficiently anticipate the changing demand for housing, an increasing qualitative mismatch threatens the housing market. In addition to the (justified) focus on energy-efficient construction that has been on the rise in recent years, 'adaptive construction' will also have to receive more attention. This implies the ability to make quick adjustments to homes during the operating period.

Furthermore, it seems that demographic developments will increasingly interact with other socio-cultural and technological trends. For instance, how household living will look like in the coming decades will also be influenced by the emergence of and interest in new forms of housing, such as co-housing, kangaroo living or shared ownership (cooperative living, garden sharing, etc.). Moreover, as car-dependent lifestyles are likely to become unattractively expensive, more people will want to live in urban environments with higher housing density. Homes will be smaller, but closer to work, school and shops. New technologies (such as robotics, alarm systems or video chat) and life-cycle compatible building should make it easier for the growing group of seniors to live independently and enable them to stay in their own homes for longer.

Care real estate has yet to peak

This brings us to the question to what extent the ageing population will impact the Belgian housing market more generally. Ageing will accelerate in the coming years. According to the Federal Planning Bureau's demographic projections, the number of over-65s will increase by 0.9 million units between 2022 and 2050. By 2050, one in four Belgians will be over 65. In principle, this leads to a large potential increase in demand for housing aimed at the elderly. In recent years, this has already led to a substantial increase in the capacity of assisted living and residential care facilities. The widespread interest by investors and property developers in this type of housing has even led to an oversupply locally, more specifically in the service flats segment. An important reason is that the elderly are staying healthy for longer and longer and are more often meeting their first care needs through home care. As a result, the effective need for care-oriented housing has so far been lower than initially estimated.

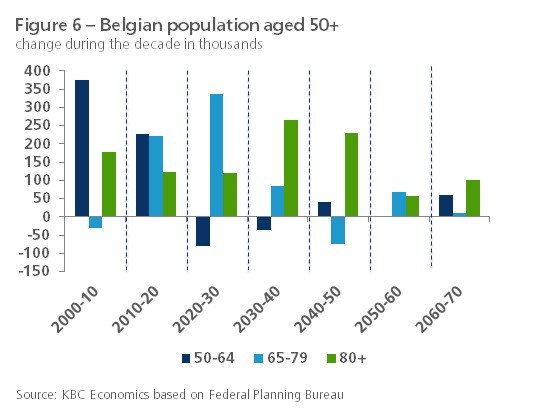

Perhaps demand for care real estate will peak later. After all, population ageing comes in waves (Figure 6). Over the current decade, the number of 65- to 79-year-olds in particular will continue to grow strongly. This is a group of active seniors who are mostly still enjoying their 'miracle years'. Only after 2030 will the increase in the number of over-80s accelerate. By 2050, about 1.3 million Belgians (about 10% of the population) will be over 80. Among this group, there are relatively many elderly people in their 'care years', which at that time will greatly increase demand for specific housing with care facilities. Perhaps the current oversupply of care real estate will gradually disappear and additional capacity of housing units may even be needed by then.

In recent years, the tendency of ageing citizens to move seems to have increased, with an increasing group wanting to switch from their often oversized home to a smaller one during their 'miracle years', in order to relieve themselves of maintenance (cleaning, garden, etc.). In this way, the ageing population increases the trend of apartmentisation discussed earlier. The vacant (mostly underused) houses can be taken up by newcomers (young families) on the housing market. On the other hand, the need for family housing from that group may shrink somewhat over the next decade. Between 2023 and 2030, the number of 25-35-year-olds (those potentially looking for their first home) in Belgium will decrease by 53,500 units. After 2030, that number will rise again.

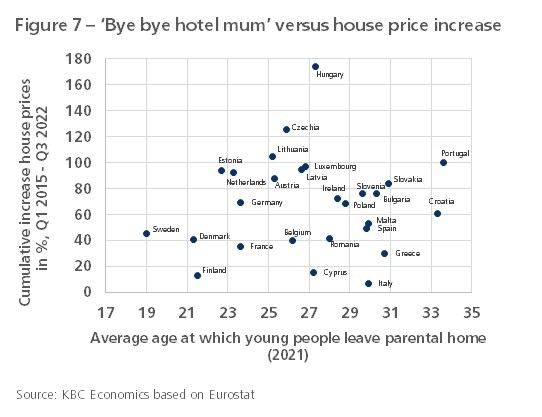

How socio-demographic changes will further affect the housing market in the coming years is not easy to predict exactly. Apart from the uncertainty regarding future demographics, this is also because, conversely, developments in the housing market may have an impact on household formation. For instance, in the absence of suitable and affordable housing, young adults may delay leaving the parental home. Not infrequently, these even return home after living independently or finishing school ('boomerang kids'). For young partners thinking of family expansion or gradually earning a higher income, it is important that they have opportunities to move into better-quality housing (move up the 'housing ladder'). Even when partners divorce, the role of the housing situation is often crucial. In flexible housing markets, they are more likely to move into a new house or flat.

In practice, however, causality between housing market dynamics and household formation is difficult to ascertain. For example, conversely, the deliberate early 'checking out' of young adults from 'hotel mum' may also drive up the demand for, and hence prices of, housing. Figure 7 illustrates that there is no clear link between the two.

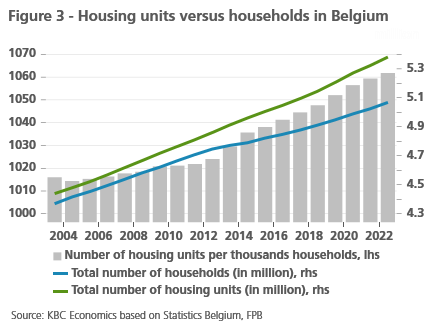

More generally, the state of the housing market (i.e. housing affordability, housing quality and environment, degree of home ownership,...) determines citizens' stay-at-home or relocation propensity. Sufficient residential mobility is often considered essential. After all, with a good flow on the housing market, households are more likely to find a home of their choice. In addition, a poorly functioning housing market with limited opportunities to move is an obstacle to a well-functioning labour market. Indeed, households are less likely to accept a job outside a reasonable distance from their current place of residence if moving is difficult. From a European perspective, residential mobility in Belgium is rather mediocre (Figure 8). In any case, residential mobility is less pronounced than commuter mobility, which helps explain the still large regional differences in unemployment and employment rates in Belgium.

Because of the ageing population, the working-age population (i.e. the potential labour supply) will also come under downward pressure in the coming years, making the labour mobility of citizens increasingly important. In addition to the existence of increasingly complex, pluralistic forms of living together, the required labour mobility also necessitates greater flexibility and diversity of the housing supply. This requires, among other things, a well-functioning private rental market, low transaction costs and the availability of sufficient housing capacity with good accessibility of job centres.