Perfect storm sends Argentina through dire straits

Less than a year ago, Argentina was the darling of financial markets. Since late-2015 President Macri had introduced sweeping economic reforms which were met with an abundance of market exuberance. Now the currency has lost 50% of its value versus the U.S. dollar this year, the economy is expected to slip back into a recession, inflation refuses to be reined in, and even a $50bn loan from the IMF has not been enough to quell market volatility. Avoiding a 2001-style crisis is still possible, but it will require deft and sure-footed responses from the government.

Argentina’s economic woes initially stem from lingering imbalances built up over years of populist economic policies. Argentina’s need to address its fiscal deficit (4.6% of GDP, 4Q-rolling, in Q1 2018), stabilize the public debt-to-GDP ratio (51% of GDP), and lower inflation (31% Y/Y in July) has been well known by most market participants since President Macri came into power. At first, markets were satisfied by Macri’s gradual approach to addressing those imbalances. ‘Search for yield’ behaviour had clearly contributed to appetite for Argentina’s relatively high yielding debt. In June 2017 Argentina was even able to issue $2.75bn in 100 year bonds with a coupon of 7%, despite a history scattered with debt defaults. More recently, however, a perfect storm of adverse developments have left Macri’s team navigating through treacherous waters.

What has changed to send the country into crisis mode?

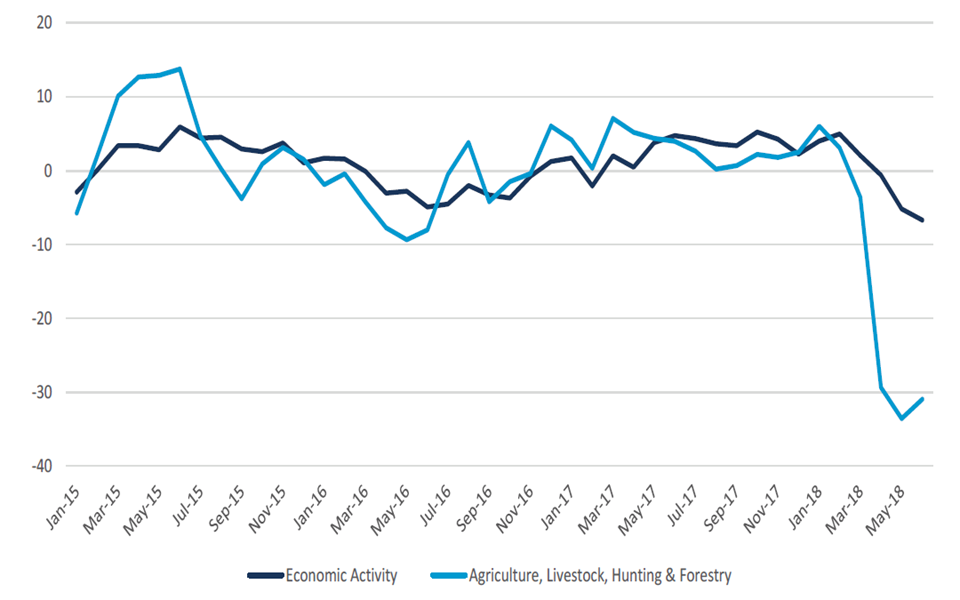

In general, external factors became much less favourable for Argentina. Interest rates in the U.S. are expected to continue rising, however, as the Fed proceeds with its rate hiking cycle and fiscal policy in the U.S. boosts growth in an economy already running close to full potential. As a result, net capital flows to emerging markets have declined markedly since Q1 2018 and the USD has appreciated at the expense of many emerging market currencies. For countries with high dollar denominated liabilities such as Argentina (34% of GDP), a stronger USD makes it more difficult to repay that debt. The decline in capital flows is likely weighing on growth in Argentina, but internal factors are at play as well. In particular, a severe drought has led to a steep decline in agricultural activity—a significant industry for Argentina’s exports (figure 1).

Figure 1 - Argentina Monthly Activity Indices (in Y/Y % change)

Policy missteps by the authorities also spooked markets. At the end of 2017 the central bank (BCRA) raised its inflation target and then eased its policy rate in January despite persistently high inflation. The second policy gaffe happened several days ago when President Macri took to YouTube to announce that he would be asking for additional early disbursements of the $50bn IMF credit line mentioned above. Though his intention was to calm markets, the announcement backfired and sent the peso sliding once again. Argentina is now expected to slip back into a recession this year before posting only slightly positive growth again in 2019. Negative growth, of course, will make it more difficult for Argentina to reach its fiscal targets.

Too little or too much? Depends who you ask.

In response to the latest currency volatility, the BCRA raised its policy rate once again from 45% to an eye-popping 60%. When this failed to stop the peso’s dive, President Macri and Treasury Minister Nicolas Dujovne announced a new fiscal plan with a faster adjustment. Specifically, the primary deficit is expected to balance in 2019 and return to a 1.0% of GDP surplus in 2020. To achieve the 2019 adjustment, the government is temporarily re-imposing export taxes on goods and services. Furthermore, the government is planning cuts worth 1.6% of GDP, which will be partially offset by a 0.3% of GDP increase in spending on social benefits. The increase in social spending is clearly a bid to soften the impact for voters who will be hardest hit by the new austerity measures. The taxes on agricultural exports in particular will weigh on Macri’s popularity with the farm sector, a politically important group that backed him in past elections due to his market-friendly policies.

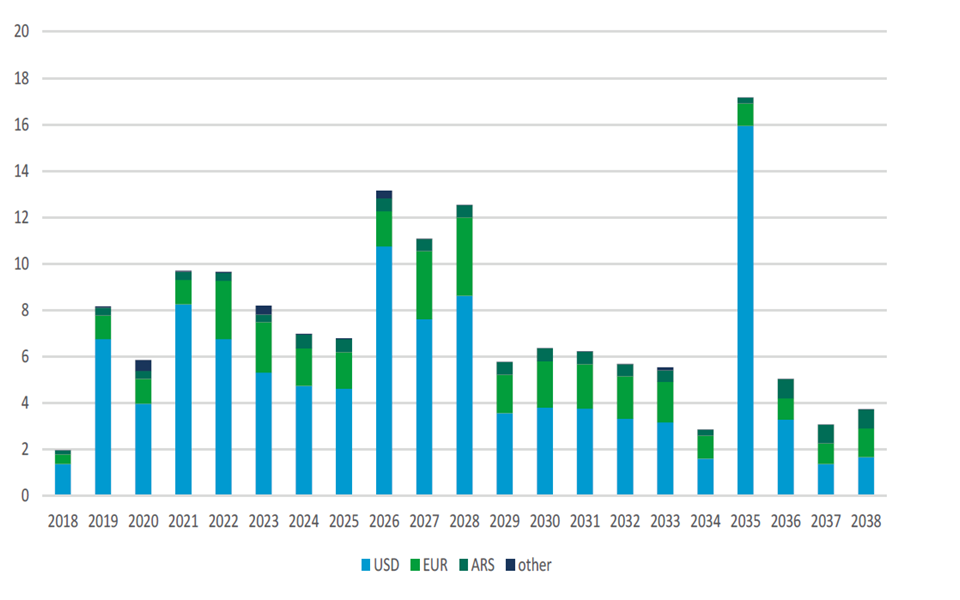

Are these adjustments enough to reassure markets? Though difficult to achieve, they are a step in the right direction. Given higher interest rates and higher risk sentiment towards emerging markets, Argentina needs to lower its reliance on financing from international capital markets. The yield on Argentina’s government bond maturing in 2021 is currently 11.6% for example. Still, even in the new plan, the Treasury foresees financing needs of $28.3bn in 2019 (excluding treasury notes, which it expects to roll over). It plans to cover this through $11.7bn in IMF funds, $2.8bn of international debt rollover, $6.4bn of domestic rollover and issuance, $2.9bn in repo, and $4.6bn from other international financial institutions. Adverse developments, however, could weigh on Argentina’s ability to secure this financing. Argentina’s current account deficit also remains substantial at 5.3% of GDP (4Q rolling) in Q1 2018. Finally, Argentina has $20bn in USD denominated debt maturing between 2018 and 2021 (figure 2).

Figure 2 - Argentina’s Debt Maturity Schedule, Principle and Interest (in USD billions)

The next several months will continue to be a precarious balancing act for the current administration. If they fail to progress on fiscal consolidation, they will continue to spin into crisis. Too much austerity, however, without any sign of stronger growth or a decline in inflation, will drag on voters’ patience. With the next general election coming up in November 2019, fear among market participants that dissatisfied voters will swing back towards populist policies could begin to mount. In sum, President Macri needs the fruits of his reform efforts, i.e., stronger growth, to begin to show. Given a less favourable external environment, in order to achieve that growth the government cannot afford any further policy missteps.