Public investments struggling to take flight

Economists have revised their views on the economic role of public budgets and public investment in recent years. While 10 years ago the predominant emphasis was on budget balance and drastic restructuring, today calls for a more active role are becoming louder and louder, especially in the euro area. The ECB is one of the most prominent voices in the choir. But the response from governments is still weak. The trend towards more public investment has been struggling to take flight.

A new vision for fiscal policy

Over the past decade, many economists have changed their views on the wisdom of implementing drastic budget cuts during an economic recession. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis (2008) and the euro crisis (2011), public finances got out of hand almost everywhere in the world. In most of the euro area countries (Belgium was an exception) the initial response to growing imbalances was to switch to substantial savings. The thought went that higher savings would restore confidence and, together with structural reforms, boost the economy. The results were much less convincing than hoped for. Drastic restructuring was rather an obstacle to recovery. It was only when fiscal consolidation took on a milder tone from 2014 that an economic boom began in the euro zone. This is now behind us.

Since the slowdown in economic growth in 2018-2019, the call for a more stimulating role for public finances has become remarkably more pronounced. One of the most prominent voices is that of the European Central Bank (ECB). The ECB has pursued a very flexible monetary policy for almost ten years, using a number of ‘exceptional’ techniques, such as a negative interest rate since mid-2014. Stimulating the economy even more through monetary policy will be difficult. Hence it is calling on fiscal policy to help.

Need for investment

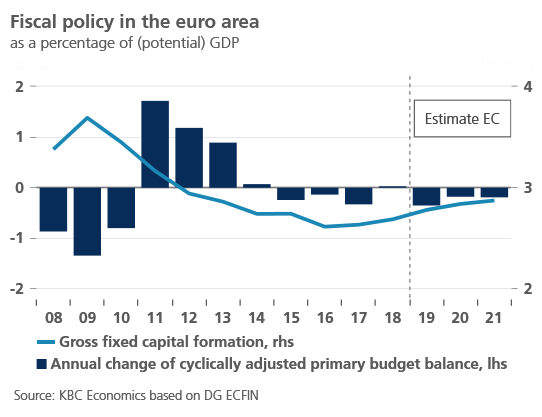

Increased public investment should be an important part of the response. After the crisis years, investment has fallen to an all-time low. In 2016, it accounted for barely 2.6% of GDP, compared with an annual average of 3.2% in 1995-2007 (see figure). Since then, only a very limited recovery has taken place. New investments are barely sufficient to compensate for the ageing of the existing infrastructure. If depreciation is taken into account, there has been no growth since 2013.

Reducing investment is often seen as a politically ‘easy’ form of saving because it affects few people directly with regard to their income or job. But this is short-sighted economically. After all, good government infrastructure is essential for economic growth and job creation. Challenges such as mobility, climate change, the environment and new technologies only add to this importance.

Largely unanswered

Despite the new vision of fiscal policy and the need for investment, the call for more public investment or a more supportive fiscal policy in general remains largely unanswered. According to the European Commission’s latest forecasts (November 2019), public investment in the euro area is expected to increase by only 0.1% of GDP in 2020-2021. This will keep investment well below the average level seen prior to the crisis years. In a broader view, overall fiscal policy will be only slightly supportive in 2020-2021.

There is an institutional handicap between words and deeds in the euro area. In the absence of a sufficiently large central budget, Member States are responsible for fiscal policy. However, many Member States are struggling with precarious public finances. This restricts their scope for a more active budgetary policy. Political preferences also differ from country to country. Countries that want to stimulate (e.g. Italy) do not have any budgetary room for manoeuvre. Those who have (e.g. Germany) are much more cautious. As a result, the necessary trend towards more government investment is difficult to set in motion.