Not national nor European champions, but world champions for Europe

Free competition on the European market is one of the basic economic principles of the EU. In a world with increasing protectionism and strategic interventions by foreign governments, Europe has to become more active in creating strong international companies too. The creation of European champions is not the best way to achieve this goal, as it undermines free competition inside the EU. Strategic alliances between European and non-European companies would be a much more sensible strategy from an economic perspective. It is urgent that Europe supports the creation of such world champions through political and policy initiatives.

Alstom-Siemens

The European Commission recently blocked Siemens’ proposed acquisition of rail industry company Alstom. Based on European competition rules, the Commission judged that this merger would lead to a too dominant position on the European market for railway signaling systems and high-speed trains. Lack of competition would lead to higher prices and lower quality of products and services. Free and sufficient competition is a fundamental building block of the European internal market. Given the limited number of players in the European rail industry, the European Commission’s recent decision makes economic sense and is probably wise. European railway companies and passengers might be hurt by too much market concentration.

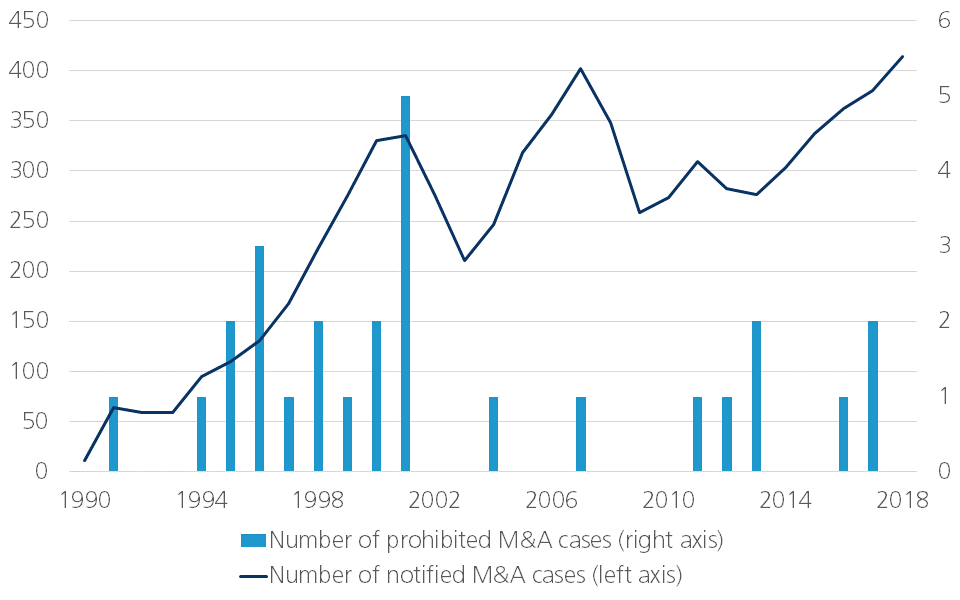

It is exceptional that the European Commission prohibits mergers or acquisitions (M&A). Generally speaking, the number of mergers and acquisitions in the EU has increased substantially in recent decades (Figure 1). This is a logical consequence of companies focusing more and more on the entire EU market. Moreover, a wider geographical presence allows firms to benefit from scale effects. Historically, many companies in Europe were restricted to their home markets. Hence it is no surprise that the gradual deepening of the European internal market triggered a gradual, but impressive increase in cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Additionally, cost advantages, increased efficiency, and improved profitability support innovation. This is often an additional argument in favour of approving many mergers and acquisitions. In each case, the European Commission has to evaluate the potential competition distortions against the economic benefits. In most cases, the economic advantages outweigh the competition concerns. In Figure 1, it appears that the number of prohibited mergers or acquisitions is remarkably low. Moreover, the Commission can approve of any merger or acquisition by imposing conditions. Conditioned on specific adaptations, like selling a particular activity or sharing technology with competitors, even relatively competition distorting alliances are acceptable.

Figure 1 - Evolution in M&A notifications and prohibitions in EU, 1990-2018

Bron: KBC Economics gebaseerd op European Commission

Safeguarding principles

European competition policy, and more precisely EU merger regulation, has gone a long way. The basis for the current legislation dates back to the early 1990s, but some later reforms have turned the current European procedures into efficient and transparent rules. Moreover, the European Commission aligns its policy to international trends, in particular US competition policy. There are also clear rules to distinguish the responsibilities of the European Commission and the EU member states’ competition authorities. At first glance, there is little need to change the current policy in a drastic way.

After the recent prohibition of the Siemens-Alstom merger, many have called for a more flexible interpretation of the current rules. The creation of large pan-European groups would strengthen these companies’ positions on global markets where larger US and Chinese players especially dominate the market. Whether or not the latter are supported by their governments, they often raise distorting barriers to entry to international markets for smaller European companies. By upscaling European companies, Europe would be able to strengthen its global position. Therefore, many call for such European champions, even if this limits free and open competition on the European market. Most people realize that national champions have caused substantial damage to the European economies in the past. Not only do they go against the dream of further European integration, but they have also been responsible for higher prices for consumers, inflation distortions, lack of innovation etc. A call for European champions would cause these same kind of issues, but at a larger, European scale. In many sectors, further consolidation remains possible from an economic perspective. However, it remains essential to safeguard the principle of sufficient competition on the European market.

Global perspective

In order to answer the call for strengthening Europe’s position on global markets, a different strategy is required. Instead of creating exclusively European champions, that could distort competition inside Europe, Europe has to engage in global competition by setting up alliances across the EU external borders. If you can’t beat them, join them, would be a better device. Such a strategy is perfectly possible within European competition rules. However, such a strategy would require further cooperation across several policy domains, including competition policy, trade policy and industrial policy. At the European level, these policy topics are often separated and institutionally divided between various directorates-general and European commissioners. At the national level, only the largest EU member states are able to develop such strategy, but they would again be against the joint European vision.

In a world with increasing protectionism, it is essential for Europe to look for international partners to jointly create world champions. Obviously, it is up to European business leaders in the first place, but political and policy backing by the EU would be welcome in the current climate of increasing government interventions. Such approach allows reconciling a free, competitive European market with an enhanced international position. It is time Europe stands up for itself.