More relevant measure of public debt would reassure

As a result of the pandemic, government budget deficits and debt ratios are rising steadily. Nevertheless, financial markets remain reassured. They do not expect a new European debt crisis. Interest rate spreads in the eurozone against Germany are again narrowing sharply and the euro has recently strengthened against the US dollar. The explanation for this paradox lies partly in the difference between the officially reported debt ratios and the debt that is actually economically relevant. After all, a significant proportion of that debt is now on the ECB’s balance sheet and is unlikely to return to the market any time soon. Ultimately, this does not make the total debt burden any lighter. It does, however, advocate the use of an additional ‘free float’ measure of government debt in the analysis of financial markets. After all, it better reflects the economic reality in the short and medium term.

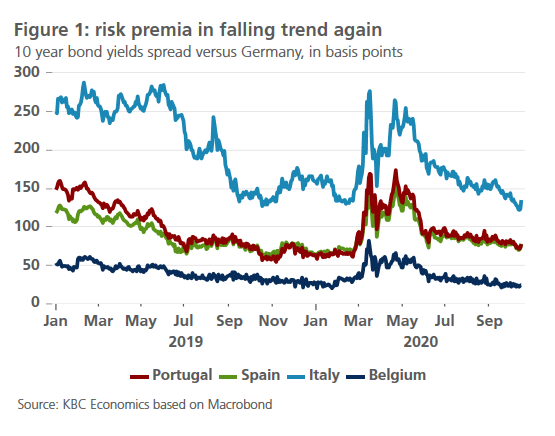

The Covid-19 pandemic is derailing public finances. For example, according to KBC’s forecasts of October 2020, the Belgian public debt will be just under 120% of GDP at the end of 2020, while the budget deficit will have risen to more than 12% of GDP. All this is happening in a context in which the European budgetary rules have been suspended for at least the financial year 2021. Nevertheless, financial markets are not overly concerned about this. There is no fear of a new debt crisis in the eurozone. On the contrary, after the initial upsurge following the outbreak of the pandemic, risk premiums on European government bonds fell again and are under even further downward pressure (Figure 1). The recent appreciation of the EUR against the USD also illustrates the confidence of international investors in the stability of the euro area.

Paradox

How can this be reconciled? The key to the answer lies in the fact that, at least in the eyes of financial markets, the figures officially published by Eurostat do not really reflect economic reality. The official debt figures do not take account of the fact that a non-negligible part of the public debt of euro countries has found its way onto the ECB balance sheet. Moreover, the amount of public debt held by the ECB continues to increase steadily as long as its purchase programmes continue.

The ECB is part of the broad definition of general government. Does this also mean that the ECB’s balance sheet may be consolidated with that of the other branches of government (see also KBC Economic Opinion of 21 June 2019 on Modern Monetary Theory)? From a pure accounting point of view, there is a case for this. When the central bank buys and finances government bonds with money creation, it essentially replaces one government debt (interest-bearing government bonds) with another (cash or bank reserves at the ECB). Moreover, in the case of the euro area, a national debt instrument is (temporarily) ‘replaced’ in this way by a debt instrument of the euro area as a whole. This is therefore an issue of European debt ‘avant la lettre’.

As long as the ECB keeps the purchased government bonds on its balance sheet, these bonds no longer have any economic significance. After all, the ECB’s policy of reinvesting at maturity means that the bonds no longer have to be refinanced by the national governments themselves. Moreover, interest payments on these bonds largely flow back to the national central banks and from there to the national treasuries via the ECB’s profit payout. This economic reality of (temporary) neutralisation of government bonds by the ECB also explains why financial markets are not worried at the moment, despite the still high level and the sharp rise in total government debt.

In 2018, the then Italian government tried to put this idea into practice in a somewhat provocative way. As part of its ‘fiscal plans’, it asked for the ECB to write off around EUR 150 billion of Italian government bonds, which is about 10% of Italy’s GDP. In the end, this did not happen, in the first place because this is legally impossible. After all, an explicit debt forgiveness by the ECB would undeniably be tantamount to monetary financing of the government, which is forbidden by the ECB mandate. However, there has never been a real political discussion on this at European level. Nevertheless, the Italian government was the first to break a taboo by considering the ECB’s purchase programmes to be what they really are in practice, i.e. (temporary) monetary financing of public debt.

Additional ‘free float’ measure useful

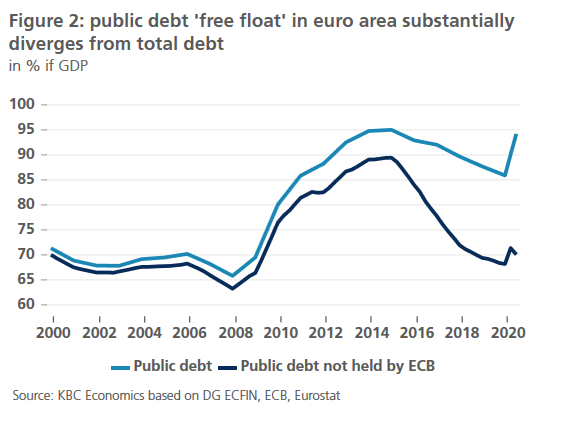

In the short term, such debt cancellation seems an tempting and easy solution. It would, however, quickly lead to a moral hazard problem with governments first accumulating more debt and then trying to put pressure on the ECB to buy and cancel this debt. Furthermore, this approach can lead to rising inflation in the longer term and poses a risk to the stability of the currency and the financial system as a whole. For this reason, such a debt cancellation or a creative adaptation of Eurostat accounting rules is not a good idea. However, the systematic reporting of a measure of ‘free float’ of public debt (Figure 2) would be particularly useful and analogous to the computation of market capitalisations on stock markets, where such a distinction is made. Such a new measure does not take into account bonds in ‘steady hands’, which will in all likelihood not be on the market in the foreseeable future.

Such a free-float measure would have the advantage for analysts that it would be much more relevant to the economic reality of debt sustainability than the current official reporting by Eurostat. Of course, this eventually does not change the actual burden of indebtedness of the governments concerned.