Italy needs, above all, to solve its growth problem

Italy is back in the spotlight, not only with the health crisis, but also in financial markets and among credit rating agencies. In all countries, the corona crisis is causing budget deficits to skyrocket and public debt to rise. Together with Greece, however, Italy is the only euro area country where, even before the current crisis, an interest snowball drove up the debt ratio. This was mainly the result of insufficient economic growth. Italy is somewhat justifiably counting on European solidarity in this crisis. But Italy also needs to strengthen its own growth potential through reforms. This is the only way to bring its public finances under control. Covid-19 is making a growth strategy more essential than ever.

Italy in the crosshairs

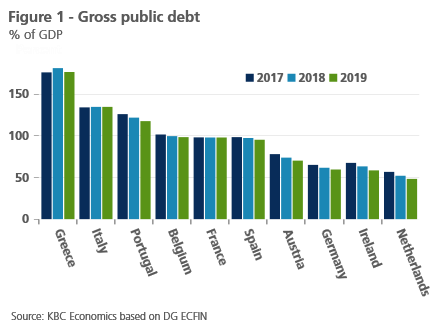

Italy is back in the spotlight. The country was the first in Europe to be hit by Covid-19. Moreover, the virus hit it hard, especially in northern Italy. As elsewhere in the world, the government is digging deep into its pockets to alleviate the economic shock. Unfortunately, the pockets of the Italian government are not so deep. After Greece, Italy has the second largest public debt in the eurozone (Figure 1). Moreover, the debt ratio has barely fallen in recent years. Even Greece did slightly better in that respect.

The cocktail of a sharp economic downturn with a sharp increase in the budget deficit makes investors in Italian public debt nervous. The interest rate differential with German government paper - a benchmark for risk-free interest rates - has risen to 2.5 percentage points in recent weeks. Although this is 'only' half the level reached during the euro crisis in 2011-2012, it is still about one percentage point higher than the risk premium on Spanish government paper, which during the euro crisis was almost as high as the Italian premium. One rating agency has already downgraded Italy’s sovereign rating, and others are watching closely.

Interest snowball

It is currently impossible to make a precise estimate of the deterioration in public finances. All in all, in its recent outlook (World Economic Outlook, April 2020), the IMF is not so pessimistic about Italy's budget deficit. Although it is expected to rise to 8.4% of GDP in 2020, it will remain smaller than in France, Spain and Belgium. However, the European Commission (Spring Forecast, May 2020) takes into account planned recovery measures in its forecasts, as the Italian government itself does in its recent Convergence Plan. Under these assumptions, the figures turn even deeper into the red - a deficit of 11.1% of GDP. Only in Spain are they similarly bad.

However, high budget deficits are not necessarily catastrophic in the current economic circumstances. They can be useful to stabilize the economy. Whether the development of public finances becomes problematic depends not only on the annual deficits and the level of debt, but also - and often even more - on its development in relation to GDP. Of course, economic growth plays a very important role in this respect. The interest rate that the government has to pay on its debt is also important.

In recent years, interest rates have been strongly influenced by the policy of the European Central Bank (ECB). With continuous purchases of government bonds, the ECB has brought interest rates to all-time lows. This has benefited Italian public finances. The average interest rate on the public debt (the implicit interest rate) fell to 2.5% in 2019, compared to 4.2% in 2012. The other euro countries enjoyed similarly cheap financing. In almost all countries, the implicit interest rate on the public debt was therefore lower than nominal GDP growth. This is extremely important because it stops the negative interest rate snowball effect on the public debt. With unchanged fiscal policy, that effect causes the debt ratio to continuously rise. In order to only stabilise the debt ratio, public finances have to be cut back every year. However, if economic growth exceeds the implicit interest rate on the debt, the debt ratio will fall automatically, at least insofar as the budgetary stance is not eased. Drastic measures are then, in principle, unnecessary.

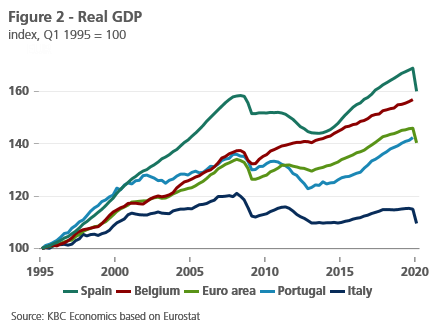

Apart from Greece, in recent years there has only been one euro country where the interest snowball has continued to roll: Italy. Not because of very high interest rates, but because of very low economic growth. As a result, the problem of Italian public finances is to a large extent the result of too little economic growth. Without a strengthening of the growth potential, public finances will never reach a path that leads to stability. Savings have to be made again and again, resulting in the impoverishment of the population.

Solving the problem of growth

The Italian growth problem is decades old (Figure 2). It is a consequence of structural handicaps such as slow productivity growth, cumbersome public administration and a low employment rate, which only improves because the working-age population is shrinking as a result of the ageing of the population. Meanwhile, political fragmentation and radicalisation prevent structural economic reforms and politicians reap success with populism and euroscepticism.

Nevertheless, the current government is counting on European solidarity for economic recovery. It can put a number of arguments on the table for this. All euro countries have a problem when Italy, the third largest economy in the euro zone, sinks into an economic quagmire. The fact that the euro area does not currently have adequate budgetary instruments to deal with a crisis such as the current one is indeed a serious construction fault. With a new government bond purchase programme, the ECB is trying to fill this gap. But it cannot continue to fill the gap forever.

However, European solidarity is not a solution if each member state does not also put its own household in order. The recovery plan for which Italy is now counting on support goes in the right direction on a number of points, for example by making drastic simplifications to administrative procedures and speeding up digitisation.

The best thing Italy can do to do itself and Europe a service is to put these intentions into practice. Only with stronger economic growth can it bring its public finances under control. At best, it will even become an example for Belgium! However, there are reasons to fear that Italy will once again fail in its intentions.